By Dave Snow and Ryan Alford

February 13, 2025

The federal government is spending several million dollars a year to do indirectly what it is unwilling to do directly: help activists wage a social justice war via the courts, far away from the public eye.

In recent years, the federal Court Challenges Program (CCP) has come under increasing political scrutiny. The program, which the Trudeau Liberals revived in 2018, distributes between $3 to $5 million each year to organizations and individuals who are engaged in litigation related to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. However, it has been criticized for, among other things, not disclosing its funding recipients, spending federal money to litigate in areas of provincial jurisdiction, and favouring progressive and activist causes (Blacklocks 2024; Van Geyn 2024).

This report uses data from the Court Challenges Program’s annual reports to show that the program’s “human rights” panel has an overwhelming progressive bias, with 96 per cent of the CCP’s “example cases” funding progressive activism. CCP-funded litigation is uniformly targeted towards the expansion of the Canadian state, an activist interpretation of the Charter, the growth of federal government authority, and the judicialization of politics more broadly. Examples of CCP-funded litigation includes:

- Requesting additional refugee protection for two individuals after they had been found likely “to have committed crimes against humanity” while part of Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe National Army

- Funding interventions in support of federal legislation, including interventions defending the federal carbon tax and federal campaign finance restrictions

- Funding cases that would involve a considerable expansion of government spending, including health funding for irregular migrants, expanded tax credits, and more generous damage claims

By contrast, we did not identify a single example of CCP funding that could be tied to anything approximating a conservative rights claim.

The recent criticism of the CCP is borne out by the data. The program lacks transparency by deceptively shielding most of its funding information due to “litigation privilege.” It centralizes federal power by funding litigation against provincial governments. And it is heavily biased towards a progressive world view that favours judicial activism as the solution every public policy issue.

The Court Challenges Program has long outlived its usefulness. It is time to shut it down.

The Court Challenges Program

The Court Challenges Program (CCP) has experienced a tumultuous history – a “political football” (Brodie 2016) cancelled by the Conservatives and revived by the Liberals. Former Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau created the program in 1978 to challenge provincial language laws. In 1985, former Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney expanded it to cover equality rights – only to cancel it in 1992. A year later, Liberal Prime Minister Jean Chrétien revived it, only to see Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper cancel it in 2006, although the component of the program that funded court challenges based on language rights was exempted from that cancellation.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reinstated the program in 2017 and it began funding cases in 2018. While the program is part of the Department of Canadian Heritage, it is administered by the Official Languages and Bilingualism Institute at the University of Ottawa (CCP 2024b). Because the CCP has been revived and cancelled over the years by simple executive action, Bill C-316 (a private member’s bill supported by the federal Liberals) was introduced in 2021 to entrench the CCP’s existence into statutory law. However, the bill died when Trudeau prorogued Parliament in January 2025.

The CCP lists two program objectives on its website: “To provide financial support to Canadians to access the courts for the litigation of test cases of national significance,” and “to help assert and clarify certain constitutional and quasi-constitutional official language rights and human rights in Canada” (CCP 2024b). The CCP offers three types of funding to people involved in prospective litigation: up to $20,000 for test case development for those who “have an idea for a test case but have not yet worked out the details”; up to $200,000 for litigation for those “persons wishing to appear before the courts to obtain a legal decision”; and up to $50,000 for legal interventions “to make arguments that are broader or have a different focus than those presented by the parties to the case, with a view to clarifying rights” (CCP 2024c, 2024d, 2024e). Over the last six years, the CCP’s expenditures have ranged between roughly $3 million to $5 million annually. In 2023–24, it received just under $6.2 million from the Department of Canadian Heritage, of which it spent $4.2 million, with a nearly $2 million surplus. Of its 2023–24 expenditures, the CCP spent nearly 28 per cent ($1.17 million) on “administration” (CCP 2024a, 25).

CCP funding recipients are determined by two “Expert Panels” of five to seven members. The Language Rights Panel determines funding for official language rights protected by the Canadian Constitution and the Official Languages Act. The Human Rights Panel determines funding for cases involving the Charter’s fundamental freedoms, democratic rights, equality rights, equality of the sexes, multiculturalism, and the right to life, liberty, and security of the person. The CCP is designed primarily to challenge federal rather than provincial policies; its website states that human rights cases “must challenge a federal law, policy or practice” and prevents language rights funding for cases that “solely” challenges provincial or territorial language polices (CCP 2024f, 2024g).

The CCP has been subject to four main criticisms over the years. First, the CCP has been criticized for favouring ideologically progressive projects, especially with respect to its equality rights funding. Political scientist (and later Chief of Staff to Prime Minister Harper) Ian Brodie (2001) showed how previous iterations of the CCP favoured groups who were interested in developing a “substantive equality” approach to Charter rights, while Professors F. L. Morton and Rainer Knopff (2000, 97) referred to the CCP as a “funding bonanza” for “equality seeking groups on the left.”

Second, the CCP has been criticized for allowing federal government intrusion into provincial affairs, particularly with respect to language rights (Morton and Knopff 2000, 95; Morton and Snow 2024, 296–97). Third, the CCP has been criticized for being an unusual and costly way for the federal government to achieve policy change. As Canadian Constitution Foundation Litigation Director Christine Van Geyn (2024) notes, “The government should not fund lawsuits against its own laws with taxpayer money.” According to this line of thinking, if the federal government thinks its policies violate Charter rights, it should change those policies directly rather than funding litigation that might result in a judicial decision striking those policies down.

Finally, the CCP has been criticized for its lack of transparency, namely its unwillingness to release information regarding its funding recipients for reasons of “litigation privilege.” As Brodie notes, while the CCP “used to allow the public to know what cases it funded and what cases it did not,” it “now serves as a way of turning our tax dollars into untraceable dark money” (Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage 2024, 25).

Because of this minimal transparency, scholars and journalists have largely been left in the dark regarding the CCP’s funding recipients since the program was re-established in 2017. This report seeks to remedy this, using the methods described below.

Method and results

Our primary method consisted of reviewing the CCP’s six publicly available annual reports from 2018–19 to 2023–24 (CCP 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024a). Each report contains budget information, statistics, and “Examples of Funded Cases.” In addition, the 2023–24 annual report lists all “concluded” cases for which CCP recipients had received funding between 2018 and March 2024, insofar as “the scope of litigation privilege to which all CCP funding recipients are legally entitled” had expired (CCP 2024a, 14). Collectively, the six annual reports contain information on 48 example cases (26 human rights and 22 language rights cases), while the 2024 annual report describes 59 confirmed instances of concluded CCP-funded litigation (27 human rights and 32 language rights cases).

Our analysis focuses primarily on the CCP’s human rights funding, as it is the best barometer of the program’s ideological diversity. Language rights cases focus on a single set of policies, namely the services, protection, and funding to official language minorities (anglophones in Quebec, francophones elsewhere). By contrast, the type of litigants eligible for CCP funding under the Human Rights Panel are, in theory, almost limitless. The Human Rights Panel could conceivably fund litigation associated with conservative causes (such as expanding freedom of expression or challenging pandemic restrictions) or progressive ones (such as expanding refugee benefits or offering progressive interpretations of LGBTQ rights). As the CCP’s core objectives – “to help assert and clarify certain constitutional and quasi-constitutional official language rights and human rights in Canada” (CCP 2024b) – are presented in non-ideological terms, it is essential to measure whether CCP funds recipients who are representative of Canada’s ideological diversity.

Analyzing the CCP’s example cases

We first analyzed the annual reports’ raw data regarding the total number of cases funded by the CCP over the last six years. In total, the CCP funded 345 of the 664 applications it received since 2018, an average of 52 per cent. The CCP funds a higher proportion of language rights applications (62 per cent) than human rights applications (47 per cent), but a higher overall number of human rights projects (36 per year) than language rights projects (22 per year).

We then analyzed the summaries of the 26 “example” human rights cases the CCP listed in its annual reports (one to two paragraphs each). These are, by definition, not a representative sample, as they constitute only 12 per cent of the 216 human rights cases the CCP has funded since 2018. More importantly, they are the cases that the CCP deliberately chooses to highlight. The 2018–19 CCP annual report also notes that example cases are those “whose recipients have authorized the CCP to disclose certain facts for the purposes of this report” (CCP 2019). Despite these selection issues, the example cases provide the best description of CCP-funded cases available in the absence of more transparent funding information.

Based on the summaries provided, we coded each “example” human rights case for 13 variables. These included the Charter rights listed, the jurisdiction of the challenged policy, the type of litigation action, the policy issue, the outcome, and whether the example matched an actual concluded case listed in the CCP’s 2024 annual report. By far the most common Charter right at issue was section 15 (equality rights: 85 per cent of examples). Section 7 (life, liberty, and security of the person) was mentioned in 46 per cent of example cases; all other rights were listed once at most. Nearly a quarter of cases (23 per cent) involved a rights claim primarily pertaining to Indigenous peoples. All 26 human rights example cases involved federal jurisdiction.

We found that numerous CCP-funded example cases sought to expand rather than limit the size of government, especially with respect to spending. Of the 26 example human rights cases, eight (31 per cent) involved CCP funding for arguments that, if successful, would have resulted in the requirement for more government or taxpayer funding. These cases included arguments for expanding disability-related funding or damages (4), health funding (1), First Nations benefits (1), employment insurance (1), and CPP funding (1).

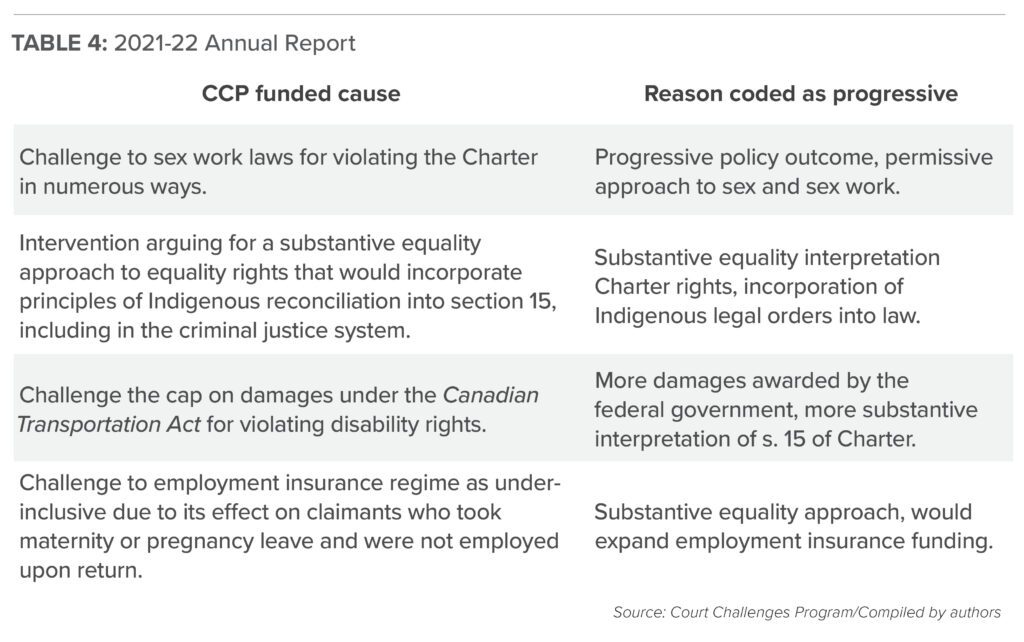

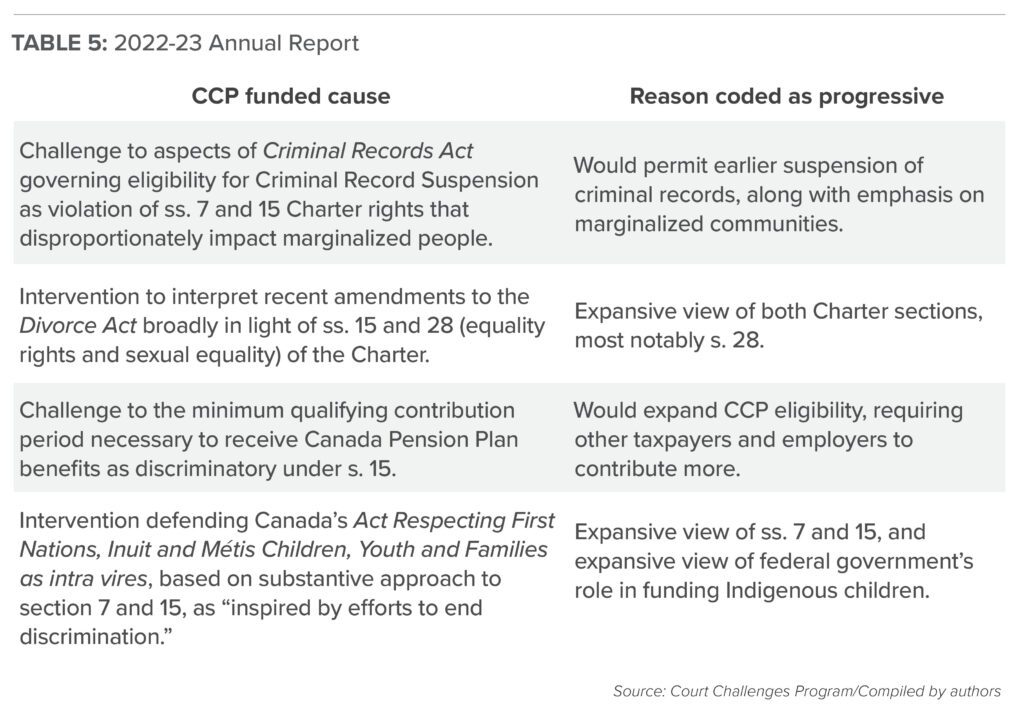

We also coded for whether it was possible to determine the ideological direction – progressive or conservative – of the funded litigation. For each example case, we read the description, categorized the policy dispute, and identified a progressive and conservative direction for that dispute. Generally, the progressive direction involved a request for an expansion of government funding and services; expanded eligibility for citizenship, refugee protection, and immigration; more lenient rules for those in the criminal justice system; or a “substantive equality” approach to discrimination. The conservative direction involved a reduction or maintenance in government funding and services; reduced or maintained eligibility for citizenship, refugee protection, and immigration; more restrictive rules for those in the criminal justice system; or an approach to equality associated with procedural fairness or equality of opportunity. The funded topic had to be clearly and obviously progressive or conservative to be coded or such; we erred on the side of selecting “unclear” in cases of ambiguity.

We anticipated that the ideological direction of the funding would often be unclear. We were wrong. Almost every example of CCP human rights funding was unquestionably progressive: 96 per cent of the funded example cases (25/26) were in an ideologically progressive direction. Examples of the recipients’ Charter claims included:

- Expanding federal health care coverage to include coverage for “irregular migrants.”

- Making the federal Disability Tax Credit more inclusive in terms of how it defines mental illness.

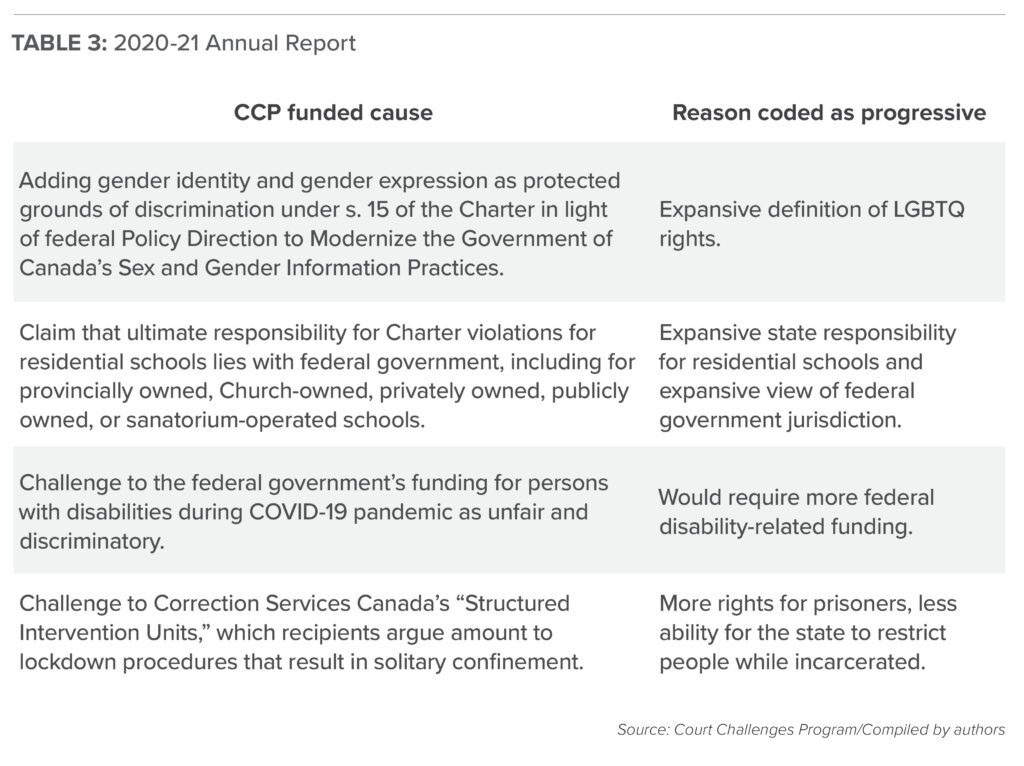

- Adding gender identity and gender expression as protected grounds of discrimination under the Charter.

- Challenging criminal prohibitions related to prostitution.

- Expanding employment insurance for those who “took maternity leave or pregnancy leave and were not employed upon their return”

- Speeding up the process for getting a Criminal Record Suspension.

- Reducing the minimum qualifying contribution period necessary to receive Canada Pension Plan benefits.

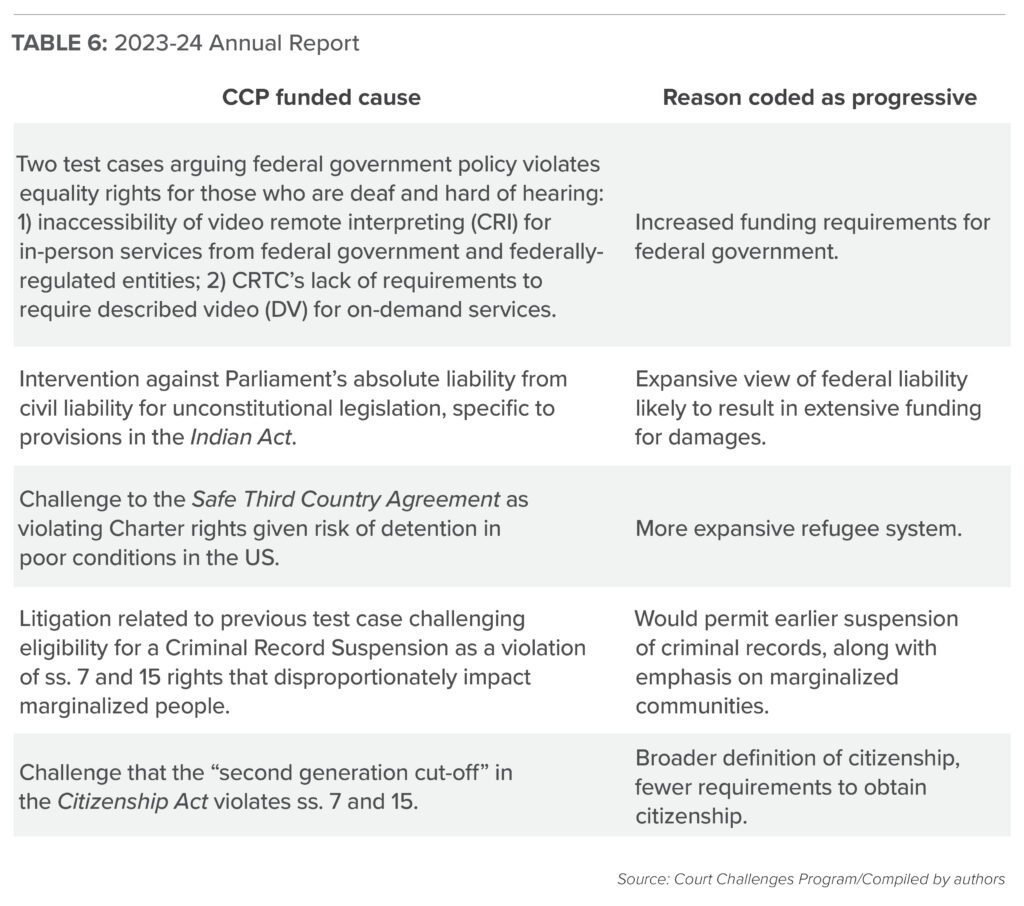

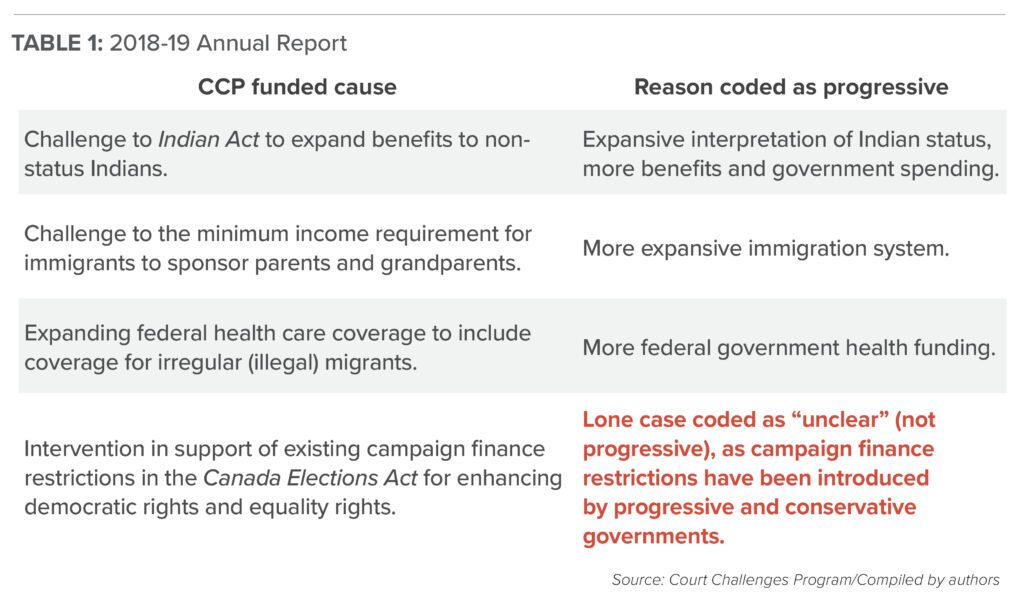

The only CCP-funded example case with an unclear policy direction was an intervention in support of existing campaign finance restrictions in the Canada Elections Act, with the recipient arguing that such restrictions enhance democratic rights and equality rights. As campaign finance restrictions have been introduced by governments of all stripes, we coded this as neither progressive nor conservative. Appendix A contains a full list of example cases, along with a brief explanation of why they were coded as progressive.

Analyzing the CCP’s concluded cases

For the first time, the new CCP’s 2023–24 annual report contains a list of funded cases that “concluded” between 2018 and March 2024. This includes CCP-funded cases that “achieved a final judgment or settlement by March 31, 2024, in which all avenues of legal recourse have been exhausted or the case has been abandoned” (CCP 2024a, 14). The CCP listed eight human rights cases in which the recipient was a party and 19 instances in which the CCP funded a human rights intervenor. The information is minimal; the CCP only includes the case name, outcome, and jurisdiction in a single line of text, with no mention of the actual funding recipient. As such, we limited our analysis to the cases in which the recipient was a party, as it was typically not possible to determine the CCP-funded intervenor.

Of the eight cases in which the funding recipient was a party, one involved a recipient who opted not to pursue the case (the report merely states “[a]s case not pursued, no case name or citation available”; CCP 2024a, 14), and one involved the same case at the Federal Court of Appeal and at the Supreme Court of Canada. This resulted in six unique cases where the CCP funded a party to the case. Five of these cases involved litigation against the Canadian government and one involved litigation against a First Nation; as the CCP does not fund Canadian governments, it is clear the litigant was the other party (the First Nations case is less clear; see below).

The six cases in which the CCP confirmed funding a party were:

- A case challenging the minimum income requirement for immigrants to sponsor their parents and grandparents (Begum v. Canada 2018; Saju Begum v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration 2019).

- A case challenging the ineligibility of refugee claims for those arriving from the United States (Seklani v. Canada 2020).

- A case challenging the exclusion of citizenship for foreign-born children whose parents were not biologically related to them (Caron c. Attorney General of Canada 2020).

- A tribunal decision challenging the cap on damages under the Canadian Transportation Act for infringing disability rights (Canadian Transportation Agency Decision No. 110-AT-A-2021).

- A case challenging the denial of refugee protection to applicants who had been deemed complicit in crimes against humanity committed by the Zimbabwe National Army (Tapambwa v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration 2019).

- A case challenging expanded eligibility criteria for membership in a First Nation (Pittman v. Ashcroft First Nation 2022).

It is impossible to determine the nature and ideological direction of CCP funding in Pittman, as the First Nation made the only Charter arguments, which were peripheral to the case (2022, paras. 80–81, 94). In the other five cases, however, the CCP funded a party whose argument was in a clearly ideologically progressive direction, seeking remedies that would create a more expansive state, whether through expanded refugee eligibility, reduced citizenship requirements, or more government money awarded for damages related to disability. As with the example cases, the CCP’s “concluded” cases clearly favoured progressive recipients.

Funding transformative litigation: case studies

In addition to the data provided above, it is worth delving more deeply into some of the cases and arguments the CCP appears to have funded. This provides a fuller sense of precisely how the CCP is helping contribute to litigation that seeks to both transform Canadian politics and put the judiciary at the heart of progressive policy change. Below, we discuss three such cases: Seklani, Power, and Tapambwa.

Seklani v. Canada (2020)

Seklani concerned the question of whether undocumented migrants who had been living in the United States would be eligible to file claims for refugee protection in Canada. This issue was the subject of considerable political controversy, as the Government of Quebec urged the federal government to close a loophole that was allowing asylum seekers to evade regulations by crossing at Roxham Road – a rural road that connects Quebec and New York State – and ultimately led to a near collapse of programs for emergency shelter and other social services in Montreal. The tolerance of an irregular process that created perverse incentives for migrants to avoid regular border crossings created an unseemly spectacle, one which exacerbated intergovernmental tensions and created the impression of an inability to implement rationally formulated and enforceable immigration policy.

At the height of the tensions over Roxham Road, the CCP appears to have funded Seklani’s claim for refugee protection in Canada. If successful, this would have expanded the Roxham Road loophole across Canada by making it impossible for the authorities to apply an expedited procedure for claimants who had transited the United States, a country that is well-known as a safe and welcoming destination for genuine refugee claimants. Thankfully, the Federal Court concluded that provisions that “ensure that refugee claimants do not make claims for refugee protection in multiple countries… does not, in any way, increase the risk that these refugee claimants will be refouled to their country of origin,” and further denied that the applicants had presented a question of general importance that would warrant certifying further review by the Federal Court of Appeal (Seklani v. Canada 2020, paras. 61–62, 69).

Canada (Attorney General) v. Power (2024)

Perhaps the most controversial and portentous constitutional case in recent memory came in Power, in which a majority of the Supreme Court of Canada authorized claims for compensation stemming from the enactment by Parliament (and by implication, provincial legislatures) of a law that the courts later deemed unconstitutional. In the words of legal scholars Stéphane Sérafin and Kerry Sun (2024), this decision caused “shockwaves” that reverberated through Canadian law, as it “embraced judicial supervision over the law-making process, unperturbed by its drastic departure from long-standing constitutional tradition… such that courts now had a right and duty to sit in judgment over Parliament and legislative decision-making.” The decision is so far-reaching that these authors argue that now “the judges on his bench are empowered to make and remake the law as they see fit, in a way that befits a legislature, not a court. The true centre of public power in Ottawa is not Parliament, but the Supreme Court.”

Based on its 2024 annual report, it appears the CCP funded a group of First Nation bands to intervene in Power, whose argument openly contemplated claims for damages on a scale previously unimagined (CCP 2024a, 11). This intervention envisioned claims for damages against Parliament for having enacted the Indian Act and other legislation, which mandated attendance at residential schools and allowed for the adoption of Indigenous children by non-Indigenous families. The intervenors’ factum notes that these programs “were and continue to be funded by money bills passed by the legislature,” which can each be the basis for damage claims under the new regime announced in Power (Fish River Cree Nation et al. 2023, 6).

Needless to say, class actions predicated on each legislative provision that funded residential schools, foster care, and adoptions could create liability on a scale exponentially higher than the billion-dollar settlements distributed to date. If taxpayers must fund tens of billions in damages owing to decades-old legislation now deemed unconstitutional, this could have a significant and unpredictable impact on the process of reconciliation, and Indigenous relations in general; to say that an important area of policy would be subsumed by the judicialization of politics would be an understatement. We are witnessing our own iteration of what judges and lawyers from other commonwealth jurisdictions have labelled the “colonization of the legal by the political process,” such that “litigation has become the pursuit of politics by other means” (Speaight 2022, 10).

Stensia Tapambwa, et al. v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration (2019)

Finally, Tapambwa involved two spouses who had been excluded from refugee protection under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act after they “were found by [Canada’s] Refugee Protection Division (RPD) to have committed crimes against humanity” when part of the Zimbabwe National Army under Robert Mugabe (Tapambwa v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration 2019, paras, 5, 17–19; see also Humphreys 2019). The Tapambwas filed to have this exclusion reconsidered but lost at the Federal Court of Appeal and were denied leave to appeal by the Supreme Court of Canada. The CCP’s 2024 annual report lists the Supreme Court decision denying leave to appeal as a case in which the CCP provided funding to a party (CCP 2024a, 14).

Little more needs to be said than this: it appears that the Court Challenges Program provided litigation funding to help two individuals remain in Canada after they had been found likely “to have committed crimes against humanity” as part of Robert Mugabe’s army. No case better signifies the ideological direction of the CCP’s funding priorities.

The future of the Court Challenges Program

Because of the assertion of lawyer-client privilege the CCP affords to its recipients, it has been difficult to assess whether the program’s funding aligns with the priorities of Canadians. Our report provides the first empirical account of who the new Court Challenges Program funds, and it confirms that the program has a clear ideological bias. Drawing from the CCP’s annual reports, we find that 96 per cent of the CCP’s examples of funded human rights litigation aimed for a progressive policy outcome, with no funding for anything approximating a conservative policy position. In 2020, the chair of the CCP’s Human Rights Panel called the CCP “a living example of social justice in action” (CCP 2020, 4). We could not have said it better ourselves.

While many government programs reflect the ideology of the government that created them, the Court Challenges Program’s progressive bias is especially problematic for three reasons. First, it provides political cover for governments to institute policy change – such as removing safeguards to guard against spurious refugee claims – that would otherwise prove unpopular. Several of the CCP-funded such as cases such as Seklani, Power, and Tapambwa indicate that the ideological agenda is not merely to enlarge governmental power, but to transform society to conform to the progressive world view. By encouraging progressive judicial activism, the CCP helps stack the deck to give left-wing litigants an advantage as they seek to constitutionalize their policy preferences. Second, it contributes to the broader judicialization of Canadian politics by sending the message that only courts can protect rights, and that governments are helpless to protect rights beyond funding litigation. This serves to undermine the important role of legislatures as rights-protecting institutions.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, it undermines the public perception of Canadian courts as politically independent arbiters of the law. As political science professor Yuan Yi Zhu has noted, such ideological uniformity in interest group litigation can “risk fuelling further the impression that courts are political arenas in which political issues are thrashed out, a perception which undermines judicial independence and trust in the legal system” (Zhu 2022). For this reason, we reject the suggestion that the CCP could be sufficiently reformed to avoid political influence. The process of selecting between prospective rights claimants is inherently political, and a reformed CCP would continue to politicize the judicial process.

Our main conclusion is that the CCP’s human rights funding recipients are uniformly progressive, and that this serves, in the words of the eminent political scientist Peter Russell (1983), to both judicialize politics and politicize the judiciary. However, our analysis also lends us to two additional conclusions regarding transparency and Canadian federalism.

First, the CCP’s arguments for obscuring funding for reasons of “litigation privilege” are without merit. The inclusion of a single line of text in the CCP’s most recent annual report for each “concluded” case does not sufficiently remedy this problem. As long as it continues to exist as a taxpayer-funded organization, the CCP should clearly disclose the full nature of its funding, whether for ongoing or concluded cases, in the interests of transparency for the Canadian public. Other recipients of government funding are made public; CCP recipients should not be able to hide their identity under the nebulous guise of “litigation privilege.”

Second, the criticism that the CCP is a centralizing institution – by using federal funding to challenge provincial laws – is true, primarily with respect to language rights. While the CCP does not fund human rights cases challenging provincial policies for violating the Charter, most of the CCP’s language rights cases do often target provincial laws. Of the 22 “example” language rights cases listed in CCP’s annual reports, only eight challenged federal policies, while the remaining 14 challenged provincial language policies (64 per cent). The CCP’s centralist bias continues to exist most clearly with respect to language rights.

Yet even the CCP’s human rights funding contains centralizing elements, as the CCP funds interventions in support of existing federal policies. For example, the CCP funded interventions supporting federal campaign finance restrictions in the Canada Elections Act and defending federal jurisdiction in a division-of-powers challenge to Indigenous family services legislation (CCP 2023, 12; 2024a, 14). Most egregiously, the CCP confirmed in 2024 that it funded two interventions in the Supreme Court case that upheld the constitutionality of the federal carbon tax (References re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act 2021). When questioned by reporters, the CCP refused to divulge precisely which intervenors it funded (Blacklock’s Reporter 2025a, 2025b), but it is clear the interventions were in support of the tax’s constitutionality – presumably by intervenors connecting environmental policy to Charter rights. Such interventions directly contradict that CCP’s guidelines that human rights funding “must challenge a federal law, policy or practice” (CCP 2024f). Despites its protestations otherwise, the CCP is using the Charter as a shield for federal power in the face of provincial jurisdictional challenges.

In 2001, Brodie wrote that “the Court Challenges Program represents the embedded state at war with itself in court,” as the federal government funded groups whose mission was to rewrite federal policies in alignment with substantive equality (2001, 376). In 2025, the Court Challenges Program remains firmly embedded into the state, but the war is over. The CCP’s progressive policy priorities firmly align with the Trudeau Liberals’, enabling yet another venue for progressive ideas to dominate federal policy.

When the CCP was reconstituted in the early years of the Trudeau government, Brodie (2016) recommended it needed to become “broader and less partisan than it has been in the past” by funding litigation that spanned the ideological spectrum, including free speech and freedom of religion cases. After more than six years of operation, the Court Challenges Program has failed this test of ideological diversity. The reconstituted CCP has consistently opted to fund projects that seek to transform the Canadian state in a uniformly progressive manner, with its human rights panel focusing on progressive projects to the exclusion of others.

While our analysis here was primarily limited to the CCP’s human rights cases, the CCP as a whole reflects a broader trend in Canadian society: the expanding role of courts (particularly the Supreme Court of Canada) as important arbiters for affecting progressive social change. In the words of former Supreme Court Justice Rosalie Abella, Canadian courts increasingly view themselves as “the final adjudicator of which contested values in a society should triumph” (2018). The CCP reflects a vision of society where courts are always the final adjudicator, and those values are always progressive. It has failed time and time again to promote a holistic or nuanced view of Charter rights and Canadian constitutionalism. It should be abolished once and for all.

About the authors

Dave Snow is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Guelph. He is the author of Assisted Reproduction Policy in Canada: Framing, Federalism, and Failure, and the co-editor (with F.L. Morton) of Law, Politics, and the Judicial Process in Canada, 5th Edition. He has a PhD in Political Science (University of Calgary) and was a Killam Postdoctoral Fellow in the Faculty of Medicine at Dalhousie University from 2014–15. He holds a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Insight Grant to empirically evaluate the way the Supreme Court of Canada permits reasonable limits on rights.

Ryan Alford is a Professor at the Bora Laskin Faculty of Law, Lakehead University. He is also a Bencher of the Law Society of Ontario and an Adjudicator of the Law Society of Ontario. Previously, he was granted standing by the Public Order Emergency Commission (the Rouleau Inquiry), and he was granted public interest standing to challenge s. 12 of the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians Act. He is also the faculty advisor to Lakehead University’s Chapter of the Runnymede Society.

References

Abella, Rosalie. 2018. “An attack on the independence of a court anywhere is an attack on all courts.” Globe and Mail, October 26, 2018. Available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-rosalie-abella-an-attack-on-the-independence-of-a-court-anywhere-is/.

Blacklock’s Reporter. 2024. “Charged $25M for Test Cases.” October 28, 2024. Available at https://www.blacklocks.ca/charged-25m-for-test-cases/.

Blacklock’s Reporter. 2025a. “Feds Paid Carbon Tax Friends.” January 22, 2025. Available at https://www.blacklocks.ca/feds-paid-carbon-tax-friends/.

Blacklock’s Reporter. 2025b. “Carbon Tax a ‘Human Right’.” January 23, 2025. Available at https://www.blacklocks.ca/carbon-tax-a-human-right/.

Brodie, Ian. 2001. “Interest Group Litigation and the Embedded State: Canada’s Court Challenges Program.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 34 (2): 357–376.

Brodie, Ian. 2016. “The Court Challenges Program rises once again.” Policy Options, April 21, 2016. Available at https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/april-2016/the-court-challenges-program-rises-once-again/.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2019. Annual Report 2018–19. Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Annual-Report-2018-2019.pdf.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2020. Annual Report 2019–20. Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CCP-Annual-Report-2019-2020-FINAL.pdf.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2021. Annual Report 2020–21. Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CCP-Annual-Report-2020-2021.pdf.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2022. Annual Report 2021–22. Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/CCP.PCJ-Annual-Report-2021-2022.pdf.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2023. Annual Report 2022–23. Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/pcj_ccp_ar23_en_240104.pdf.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2024a. Annual Report 2023-24. Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/CCP_AnnualReport_2023-2024.pdf.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2024b. “Who We Are.” Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/who-we-are/.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2024c. “Development of Test Cases: Human Rights.” Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/funding-areas-human-rights/development-of-test-cases-human-rights/.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2024d. “Litigation: Human Rights.” Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/funding-areas-human-rights/litigation-human-rights/.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2024e. “Legal Interventions: Human Rights.” Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/funding-areas-human-rights/legal-interventions-human-rights/.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2024f. “Eligibility Criteria: Development of Test Cases.” Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/rights-human-rights/development-of-test-cases-human-rights-rights/.

Court Challenges Program [CCP]. 2024g. “Eligibility Criteria: Development of Test Cases.” Available at https://pcj-ccp.ca/rights-official-language-rights/development-of-test-cases-languages-rights-rights/.

Humphreys, Aidrian. 2019. “Zimbabwe couple complicit in crimes against humanity for serving in Mugabe’s army lose bid to stay in Canada.” National Post, February 25, 2019. Available at https://nationalpost.com/news/zimbabwe-couple-complicit-in-crimes-against-humanity-for-serving-in-mugabes-army-lose-bid-to-stay-in-canada.

Morton, F.L., and Rainer Knopff. 2000. The Charter Revolution and the Court Party. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

Morton, F.L., and Dave Snow. 2024. Law, Politics, and the Judicial Process in Canada. 5th Edition. Calgary: University of Calgary Press.

Russell, Peter H. 1983. “The Political Purposes of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.” Canadian Bar Review 61: 30–54.

Sérafin, Stéphane, and Kerry Sun. 2024. “Unchecked judicial power — that’s Chief Justice Wagner’s vision for Canada.” National Post, October 9. Available at https://nationalpost.com/opinion/opinion-unchecked-judicial-power-thats-chief-justice-wagners-vision-for-canada.

Speaight, Anthony. 2022. “How and Why to Constrain Interveners and Depoliticise Our Courts.” Policy Exchange. Available at https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/How-and-Why-to-Constrain-Interveners-and-Depoliticise-Our-Courts.pdf.

Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage. 2024. 44th Evidence, no. 116. 44th Parliament, 1st Session, April 18, 2024. Available at https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/44-1/CHPC/meeting-116/evidence.

Fish River Cree Nation, Fisher River Cree Nation, Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, Manto Sipi Cree Nation, and Lake Manitoba First Nation. 2023. “Factum of the Interveners.” Canada (Attorney General) v. Power. File Number 40241. Available at https://www.scc-csc.ca/WebDocuments-DocumentsWeb/40241/FM230_Intervener_Fisher-River-Cree-Nation-et-al.pdf.

Van Geyn, Christine. 2024. “When governments pay to sue themselves on your dime.” The Line, May 15, 2024. Available at https://www.readtheline.ca/p/christine-van-geyn-when-governments.

Zhu, Yuan Yi. 2022. “How the Government could prevent charities turning the courts into a political battlefield.” Conservative Home, December 21, 2022. Available at https://conservativehome.com/2022/12/21/yuan-yi-zhu-how-the-government-could-prevent-charities-turning-the-courts-into-a-political-battlefield/.

Cases Cited

Begum v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2018 FCA 181 (CanLII), [2019] 2 FCR 488

Saju Begum v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, 2019 CanLII 32863 (SCC)

Canada (Attorney General) v. Power, 2024 SCC 26

Canadian Transportation Agency Decision No. 110-AT-A-2021. https://otc-cta.gc.ca/node/570613

Caron c. Attorney General of Canada, 2020 QCCS 2700 (CanLII)

Pittman v. Ashcroft First Nation, 2022 FC 1380 (CanLII)

Seklani v. Canada, 2020 FC 778

Stensia Tapambwa, et al. v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, 2019 CanLII 62557 (SCC)

Tapambwa v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2019 FCA 34 (CanLII), [2020] 1 FCR 700

Stensia Tapambwa, et al. v. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, 2019 CanLII 62557 (SCC)

Tapambwa v. Canada (Citizenship and Immigration), 2019 FCA 34 (CanLII), [2020] 1 FCR 700

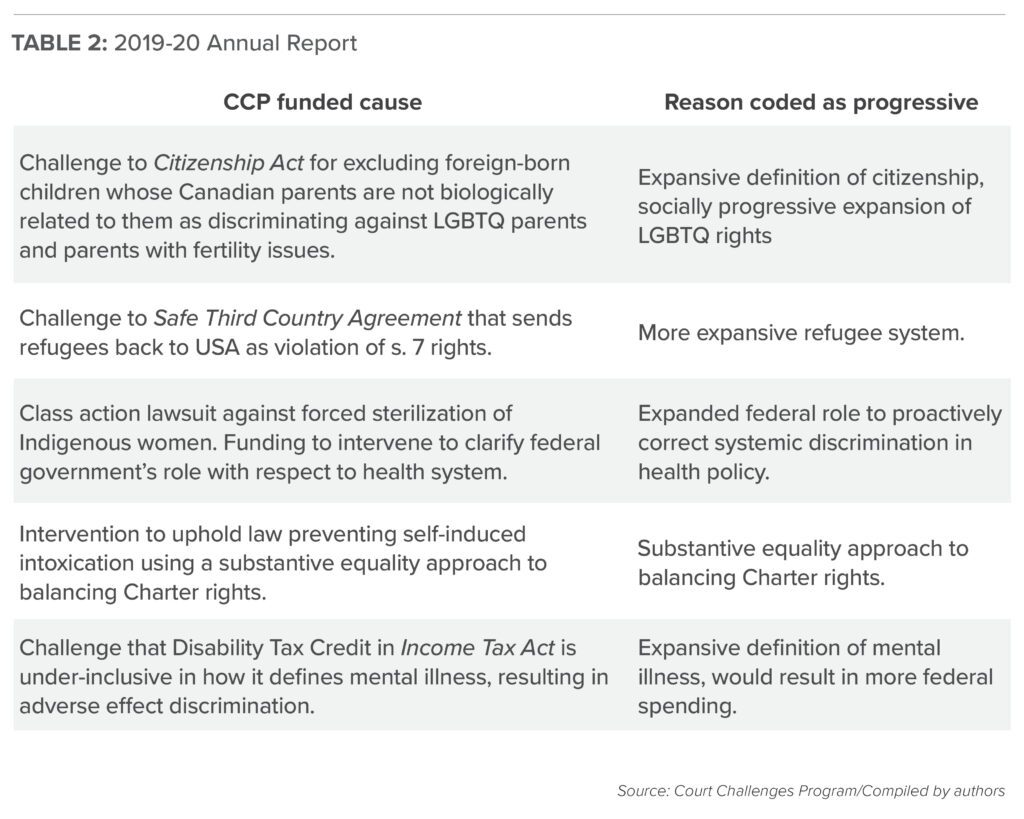

Appendix A – List of Example Cases

2018–19 Annual Report

2019–2020 Annual Report

2020–21 Annual Report

2021–22 Annual Report

2022–23 Annual Report

2023–24 Annual Report