This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Paul W. Bennett, November 13, 2024

Students skipping classes is a tale as old as systemic education itself. Indeed, chronic absenteeism rates among students have risen and are becoming normalized in the wake of the pandemic education disruption. Teachers missing class as well, though, is another problem entirely. Teacher absences from class are up, but—until now—this has attracted less attention, particularly in Canadian K-12 education.

Rarely publicly reported on, the sheer absence of reliable, consistent, and system-wide data on teacher absenteeism has made it very difficult to assess the scale and dimensions of the problem confronting school systems and educational organizations in recent decades.

The dam broke in Ontario this past summer with the release of shocking new data on the astronomical rates of teacher and staff absenteeism since the pandemic. It did not come from regional school districts but rather from the School Boards’ Co-operative Inc. (SBCI), a not-for-profit mandated to monitor Ontario school boards to help improve efficiencies and decrease costs.

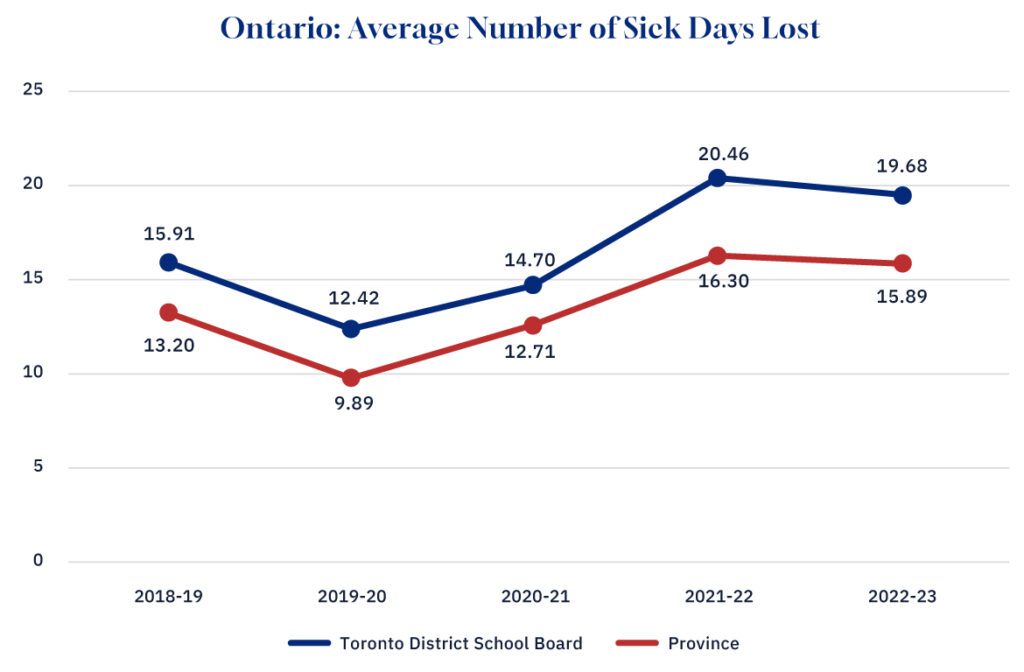

School district staff absences are now “pervasive.” Sick day records at the Toronto District School Board in the 2022-23 academic year totalled nearly 20 days, compared to Ontario’s average of about 16.

Those days cost roughly $213 million, or 8.71 percent of the board’s total payroll, including the funds needed to staff a replacement teacher. The academic year before (2021-2022), sick calls at the TDSB exceeded 20 days and cost the board $233 million, or 9.46 percent of total payroll.

The public reaction was swift and left the Toronto DSB scrambling to respond. The TDSB responded predictably, pledging to focus on providing more supports and addressing the challenges of employee and student well-being. It sparked major upheaval in the Thames Valley District School Board based in London, Ont., where the system was already facing an $18-million deficit. Shortly thereafter, the actual report completely disappeared from the SBCI public website.

The hidden problem of teacher absenteeism

Teacher absenteeism is not new but the lingering impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has made it more visible in classrooms. Federal data in the United States demonstrated that in 2022 many U.S. teachers missed 10 percent or more workdays after schools reopened in-person instruction. The National Center for Education Statistics showed in the same report a staggering 72 percent surge in teacher absenteeism over pre-pandemic years.

Teacher absence data from the United States provides a rough benchmark. One oft-cited 2020 National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) study provided a fascinating set of findings. Overall, prior to the pandemic, teacher absence rates were significantly lower and the contributing factors were likely different.

The pre-pandemic NCTQ study found that teachers with more experience tended to be absent more frequently, suggesting that job security concerns have an effect on novice teachers’ absences. Teachers were reportedly absent mainly when they were sick (five days on average), rather than for personal reasons (two days on average), and used up about half of their available leave for both categories.

On average, teachers in districts with higher percentages of students of colour tended to be absent less frequently. Teachers’ pay had a small positive relationship with teachers’ attendance.

When it came to the impact on students, teacher absence was found to have adversely affected mathematics proficiency, and most acutely when teachers missed 10 days or more a year.

A recent ground-breaking Alberta study began to address the research gap in Canada by examining the prevalence of sick days among teachers in three representative provinces: Alberta, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador.

Surveying self-reported data from 763 teachers who took sick leave in 2021-22 and 2022-23, the study found a strong association between sick days and “the prevalence and severity of high stress, low resilience, burnout, anxiety, and depression among educators.”

The key findings

Overall, this study reported that participants in a Wellness4Teachers program who took 11 or more sick days in the preceding academic year were at least three times more likely to report “high stress” and “emotional exhaustion” than those who took no sick days. They were also more likely to present with high stress in the following school year.

Educators with six or more sick days in the preceding academic year were at least twice as likely to present with burnout or “depersonalization” compared to those without sick days. Teaching, as a human service occupation, relies heavily on interpersonal interactions. So, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job severely hinder teachers’ ability to perform their duties, leading to more frequent sick absences.

This amounts to a compounding effect, putting teachers at an increased risk of taking additional sick days in the current school year. Because teaching entails specific skills and training, the researchers claim that it’s challenging to replace experienced educator. Providing programmatic and emotional supports is therefore of vital importance to reduce the tendency for increased sick leaves

Review of sick day policies

Absenteeism is higher in teaching than in other professions and has been directly linked to teacher mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety. Teachers experience higher rates of psychological disorders compared to other professions and are at higher risk of workplace stress, leading to burnout, depression, and other psychosomatic symptoms. The stress experienced by teachers can be linked to three major overlapping problems: burnout, anxiety, and depression, all of which profoundly impact their health, well-being, effectiveness, or productivity.

The persistence of teacher absenteeism in post-pandemic schools is bound to raise questions about the role of policy in contributing to or perpetuating the problem. In Ontario, for example, teachers are entitled to 11 sick days per year at full pay and 120 days at 90 percent of their salary. Changes in provincial policy phasing out the banking of sick days may be a factor, but that needs to be more fully researched to assess its unintended consequences.

The need to support increased numbers of kids with learning challenges and complex needs should be understood as a contributing factor. Educational assistants and school custodians in the Toronto DSB are the frontline workers here, and they booked off time in 2023-24 at an average of 27.23 and 25.14 days, respectively. That’s higher than for TDSB regular teachers, averaging 20.80 days in elementary schools and 17.99 in secondary schools.

Curbing mental health days

Since the massive pandemic disruption, we are now more aware of the critical importance of in-person instruction. The absence of educators in schools denies students access to their positive effects in the classroom. Setting aside the serious financial costs, absenteeism also erodes morale, negatively influencing the organization’s overall climate and productivity.

It also has broader implications outside the schools’ walls, adversely affecting public confidence in our school systems and labour productivity in other sectors.

Post-pandemic, teachers are more inclined to take “mental health days” as a means of self-care and stress relief. It’s up to teachers to take personal proactive steps to prioritize mental health, self-care, and healthy activities in daily life.

Overall, teacher absenteeism requires a broader, multi-faceted approach, starting with district and school leadership, a review of sick day policy, and pro-active measures properly supported by provincial school systems.