The government’s new defence policy contains a lot of positive elements, writes Craig Stone. But it also raises serious questions on its promise of significant spending increases and impact on procurement.

The government’s new defence policy contains a lot of positive elements, writes Craig Stone. But it also raises serious questions on its promise of significant spending increases and impact on procurement.

By Craig Stone, June 8, 2017

On June 7, the government presented its new defence policy, Strong Secure and Engaged: Canada’s Defence Policy, making the point that it was a defence policy arising from extensive consultation and providing predictable, long term funding to Canada’s armed forces and defence department.

The new defence policy has in fact both positive and negative aspects. The focus on people, the commitment to increase female representation to 25 percent by 2025, the commitment to 15 future naval vessels and 88 new fighter aircraft, an articulation of ambition and an intention to connect defence and innovation are just a few of the positive aspects of the policy. Unfortunately, as is always the case for defence policy space, the ultimate evidence for those who are critical of government is when actual money is placed into the budget so that the military and Canadian industry can make decisions moving forward. In this context, the numbers in the budget are much more problematic.

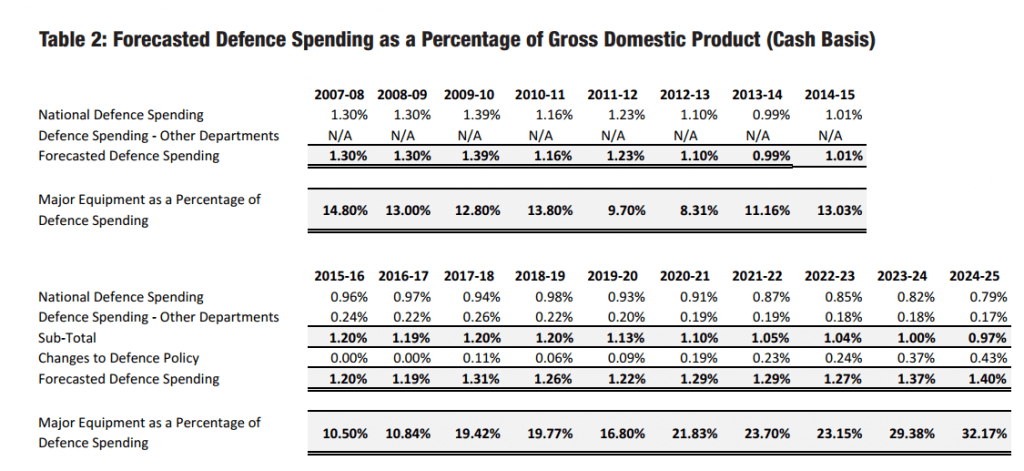

The government has committed to increase defence spending to 1.4 percent of GDP by 2024-25. This will be done by capturing other expenditures allowed under NATO’s definition of defence expenditures. The table in the policy statement indicates that actual defence spending in the Department of National Defence (DND) is going to decrease as a percentage of GDP while spending captured in other government departments – Veterans Affairs, for example – will increase.

The ultimate evidence for those who are critical of government is when actual money is placed into the budget.

The policy statement indicates a clear priority to people and looking after veterans so there will be more funding – a positive no doubt but not necessarily positive if you remain inside DND. But the table on page 46 of the document (see below) can be interpreted differently depending on what line in the table you want to focus on. Spending on defence will decrease to 0.79 percent of GDP. Individuals need to have confidence the table’s Changes to Defence Policy line, which indicates a spending increase of 0.43 percent of GDP, will actually come to fruition in order to achieve 1.4 percent of GDP.

In the larger context, there is a commitment to grow the budget by 70 percent from $18.9B in in 2016-17 to $32.7B in 2026-27. An additional $62.3B in the next two decades. There are some issues with this data. Based on the government’s projected growth of the Canadian Economy in their 2017 budget data 1.4 percent of GDP is approximately $35B vice $32.7B, a difference of just over $2B. And this is not the first policy statement that has promised predictable long term stable funding. The challenge for the leadership is articulating to the critics how any of this is actually new money that is different from previous commitments already in the Finance Department’s fiscal framework for defence. The Ministers answer to this question from the media was not helpful. Stating Canadians should have confidence in the intent because it is written in the policy captures the “meaningless defence policy” space.

This then is the challenge for senior officials in defence. They are required as Public Servants to be positive and talk about why this is a good policy for defence. Unfortunately, there will be many who will focus on the negative and what is not in the policy statement. This was obvious during the question period after the Minister released the policy statement. What about peacekeeping and why do we need more people because we have no threat are just two examples of reasonable questions to be asked. Some were answered well and some were avoided, as might be expected because the detail has yet to be finalized.

Canadians should also not expect that all of the issues addressed in the policy are ready to be implemented right away. This policy document gives the Chief of the Defence Staff, General Jonathan Vance, the policy guidance he needs to start to develop the detailed plans for how to achieve the governments objectives. This is not to imply that the members of the department have not been working on the plans but rather to acknowledge that options for how DND will achieve the governments’ policy objectives must now be presented to Cabinet, be coordinated with other government departments, funding authorities obtained from Treasury Board, among other tasks, so that new funding (if there really is new funding) can be identified and placed into the process for next years’ 2018-19 Budget.

Moving to perhaps “the elephant in the room,” what does the policy document mean for procurement and industry. Here the case is much less clear if you are in industry. The policy reiterates much of what was in the previous defence procurement strategy and does indicate an intention to grow the procurement specialist inside DND by 60 folks, but for those who are critical of the policy statement, the lack of clearly articulated spending plans in the next few years only highlights the uncertainty of short term funding for industry if they are trying to make longer term investment decisions.

Money is already set aside for things that are underway like the Arctic Offshore Patrol Vessel and planning is underway for other new equipment projects.

Most of the informed public only have a basic understanding of the complexity of the procurement process and how long it takes to bring an identified capability deficiency to fruition. It is unfortunately a much more cumbersome and bureaucratic process that is designed to meet multiple government objectives. Money is already set aside for things that are underway like the Arctic Offshore Patrol Vessel and planning is underway for other new equipment projects. Developing detailed requirements, engaging with industry and finalizing costs takes time, particularly if you also need to ensure it is done in an open and transparent manner that also allows for competition and economic benefit for Canadian Industry. Canada’s military could sole source all of its defence requirements but that would not serve Canadian taxpayers very well because sole sourcing would more often than not end up being with a foreign company with little benefit to Canadian industry.

Engagement with industry and the other players in the government ensures that there is consideration to growing Canadian industry, jobs and economic activity in value added sectors of the economy. This is not to say that improvement cannot be made – the current process and its number of steps for approval will not allow us to be successful in the future and that is why the policy statement reiterates commitments from the previous defence procurement strategy to reduce timelines, enhance contracting authorities, and provide report cards on activity. The process needs to change but more importantly, the number of individuals working in this area needs to increase and adding the 60additional people will help. The irony is that the current Liberal government is living with the decisions by the Liberal government in the 1990s to significantly reduce the number of people dedicated to project management, procurement contracting, and industry engagement.

Reiterating the premise at the beginning, there is lots that is positive in the new policy statement and lots that is potentially negative or at least highly uncertain. Unfortunately, the senior leadership will be focussing on answering those who believe it is another meaningless defence policy.

Just because the document says the government is committed to long term stable defence funding does not mean they will follow through on it. Most of past defence policy statement have made the same commitment and then shortly thereafter started to cut funding because circumstances change. That is why over 2.5B was removed from the budget two years after the previous government promised long term stable funding. You cannot predict the next financial crisis that will change the government’s priorities.

Craig Stone is an Associate Professor and defence economist who teaches Strategic Resource Management and Institutional Policy at the Canadian Forces College in the Department of Defence Studies, Royal Military College of Canada.