This article originally appeared in the Financial Post. Below is an excerpt from the article, which can be read in full here.

By Philip Cross, September 2, 2022

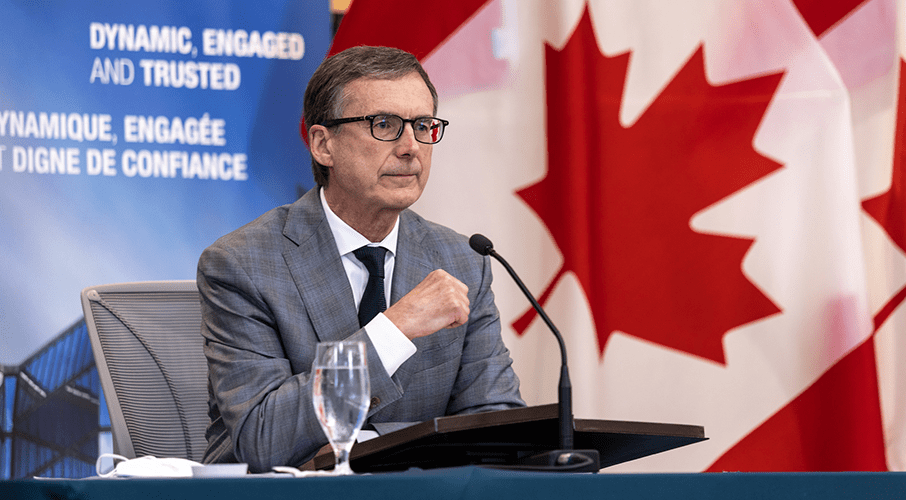

Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem recently cautioned business leaders not to give in to higher wage demands from workers trying to keep up with rising prices. “Don’t build that into longer-term contracts,” he told the Canadian Federation of Independent Business. “Don’t build that into wage contracts. It is going to take some time, but you can be confident that inflation will come down.”

Implicitly, Macklem was saying real wages will fall substantially in 2022 as prices soar, hardly a popular idea but a necessity if we’re to avoid a wage-price spiral. If wages do accelerate to catch up with our current inflation rate of about eight per cent, that means employers’ labour costs — the largest part of their costs — will increase markedly, triggering another round of price hikes. That is exactly what central banks need to avoid if inflation is to return to its target rate of two per cent by the end of next year.

The erosion of real incomes due to inflation in 2022 sounds decidedly unappealing but it merely reverses pandemic gains far exceeding what could be justified by productivity. Between the onset of the pandemic and the second quarter of 2021, when stimulus peaked, real household disposable income rose 3.0 per cent even as GDP shrank 2.8 per cent and labour productivity stagnated. Wage hikes in excess of productivity inevitably result in higher unit labour costs, which aggravate the upward pressure on prices. Since then, real GDP has risen 4.6 per cent while household incomes have shrunk 1.3 per cent, essentially re-aligning their growth since the pandemic began. The one constant throughout has been the mediocre performance of productivity, which has declined overall by 1.3 per cent.

***TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE, VISIT THE FINANCIAL POST HERE***