Independently of the great Red River and Saskatchewan country lying between Canada and the Rocky Mountains, and the gold-bearing district of British Columbia between those mountains and the Pacific – an immense country now fast rising into importance – we find these five British North American provinces, with a population larger than the old colonies had at the time that the ignorance and injustice of the British Government lost them – the brightest gem of the Crown of England.

The population of British North America exceeds that of Greece, Denmark, Hanover, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Portugal, Saxony, Switzerland, or Würtemberg, and nearly equals that of Bavaria or Belgium. Her area is greater than that of all those countries put together, with Russia, England, Ireland and Scotland added. Her exports are greater than were those of the United States in 1790, whose exports as recently as 1830 were not double what Canada now boasts.

The revenue of British North America exceeds that of Greece, Saxony, or Switzerland, and is nearly as large as that of Denmark, while her tonnage surpasses that possessed by the United States in 1790.

In view of all these facts, it will not be considered strange that, looking to the future, conscious of the boundless expansion of which our country and our resources are capable, we should begin to inquire whether our political position is such as we are relatively entitled to among the communities of the earth.

The time best suited to the calm and rational investigation of such questions is previous to any imperative necessity arising for an immediate solution. The very nature of colonial institutions involves continual change to meet the altered circumstances which progress induces. The present comparatively free institutions which we enjoy would have been impracticable at the commencement of our history. When first brought under British rule, Canadians were content to have English laws enforced simply by proclamation. Then legislation by a governor and council, under the Constitution given them by the Quebec Bill, was all that was required for the seventeen years previous to 1791, when a Legislature was first constituted. It is worthy of remark that a large portion of the inhabitants then petitioned against this extension of their privileges, as unsuited to their condition. Even down to the union of the Canadas in 1840, self-government was anything but conceded to that colony. Lord Sydenham wrote in December, 1839:

‘My Ministers vote against me. I govern through the Opposition, who are truly Her Majesty’s.’

It will thus be seen that the political institutions of a colony must vary with its changing condition. The system of government conceded by Lord John Russell, and hailed with such enthusiasm as a sovereign panacea for every political ill a few years since, has not given universal satisfaction or been unattended with difficulties. In Prince Edward Island the departmental system, as practised in the other provinces, has been abandoned, after a vain attempt to make it work satisfactorily. In Newfoundland it may be said to be almost impracticable. In Canada the talented leader of the Opposition, the Hon. George Brown, has declared the system of responsible government as practised in that colony to be ‘a delusion and a snare,’ while the Conservative Ministry, who are in power there, represented in a State paper to the British Government in 1858 that:

‘Very grave difficulties now present themselves in conducting the government of Canada in such a manner as to show due regard to the wishes of its numerous population,’ and requested the parent State to authorise a meeting of delegates from the different provinces to discuss constitutional changes of the most extensive character. More need not be said to show that the discussion of questions relating to our political position is by no means premature.

Let us, then, inquire whether our present political status is such as to meet our material progress and satisfy the natural and laudable ambition of free and intelligent minds.

It must be evident to everyone in the least degree acquainted with our history, that at present we are without name or nationality – comparatively destitute of influence and of the means of occupying the position to which we may justly aspire. What is a British-American but a man regarded as a mere dependent upon an Empire which, however great and glorious, does not recognise him as entitled to any voice in her Senate, or possessing any interests worthy of Imperial regard. This may seem harsh, but the past is pregnant with illustrations of its truth. What voice or influence had New Brunswick when an English peer settled most amicably the dispute with an adjoining country by giving away a large and important slice of her territory to a foreign power? Where were the interests of these Maritime Provinces when another English nobleman relieved England of the necessity of protecting our fisheries by giving them away to the same Republic, without obtaining any adequate consideration for a sacrifice so immense?

Mr. Lindsay, the able and enlightened advocate of the shipping interest of England, found that he had visited the United States on a bootless errand – that the only price for which they could be induced to surrender the enjoyment of their coasting trade to British vessels was the long coveted permission to enjoy over five thousand miles of sea-coast in common with ourselves, and reap a rich reward from our fishing grounds while they establish themselves as a leading maritime power.

It may be said that we were a party to the negotiation of that treaty, but it is not so. The very mode in which the colonies interested were invited to participate was simply an insult. They were permitted to concur, but not consulted in the arrangements.

The Reciprocity Treaty has undoubtedly largely benefited both the provinces and our American neighbours, and with the concession to us of the right to register colonial-built vessels and enjoy the coasting trade would have been worthy of its name.

The proposal to abrogate that treaty, although mooted in the States, is not very likely to be seriously entertained by a country whose trade with the British North American colonies has under its influence more than trebled within four years, having risen from sixteen million in 1852 to fifty million in 1856, employing a tonnage of over three and a half millions of tons upon the lakes and the Atlantic coast, one half of which belonged to the States.

The evidence that these colonies are destitute of all influence with the Imperial Government lies around us in thick profusion. Never were the interests and feeling of subjects more trifled with than have been ours in a question of the most vital importance – the Inter-colonial Railway. From the time that astute and far-seeing statesman, Earl Durham, proposed the statesmanlike project of connecting these colonies by rail, the various provinces have manifested the deepest interest in it, although it was a work fraught with Imperial interests quite as great as any of a colonial character. These provinces cheerfully defrayed the heavy expense attending the survey organised by Mr. Gladstone; successive Secretaries of State have entertained that great scheme, and committed the faith of the British Government to it, but only to end in disappointment – alleging difficulties as to the route and the want of agreement among the different provinces.

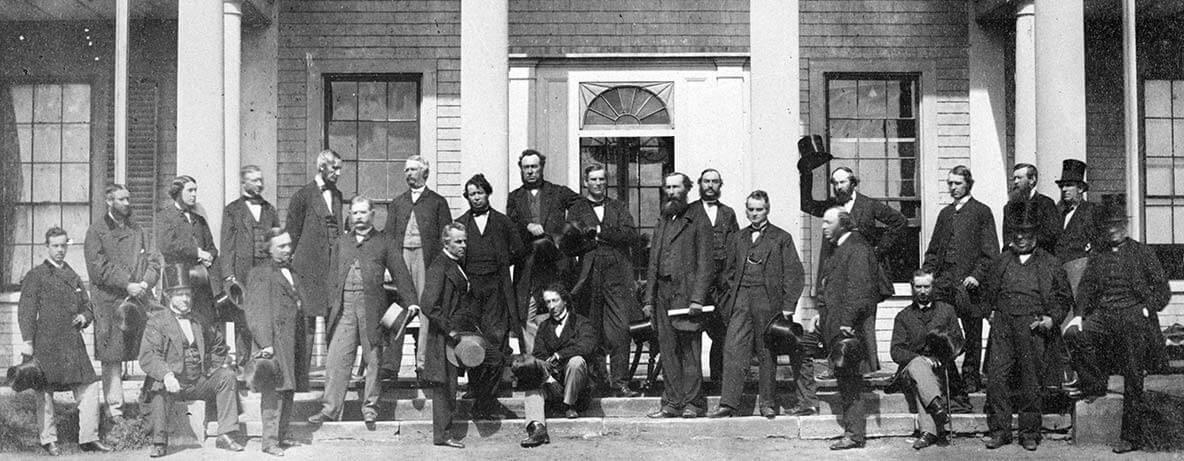

Under the impression that the value of this great national was well as colonial undertaking was really appreciated in England, and encouraged by a dispatch which said that the subject would shortly receive the serious consideration of the British Cabinet, the three Governments of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia sent a joint delegation to London in 1858. While I feel bound to admit that we were treated at the Colonial Office with all due courtesy, and had every personal attention bestowed upon us which we could desire, it was but too evident that the Cabinet were too much engaged with their own immediate interests to take any very deep concern in a subject so remote, and urged by parties who were unable to bring to their support votes in the Commons. Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton did seem a little aroused to the importance of the question, and concurred in the feasibility of our proposal; and Mr. Disraeli, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, to whom we were referred, admitted that the question had assumed a really practicable shape; yet, although the three provinces who, unaided, had done so much towards accomplishing this national work unitedly pressed upon the attention of the British Government a scheme which would have completed it without any increased drain upon the British Exchequer, or have involved the outlay of an additional shilling – as we merely required subsidies for the performance of the services for which the Imperial Government now pays a much larger sum – without taking the trouble even to verify the accuracy of our calculations by reference to the public departments, this country was coolly informed that ‘Her Majesty’s Government have not found themselves at liberty to accede to the proposal.’

As a striking commentary upon the impotent position we occupy with the parent State, it may be added that while these vital interests, so deeply affecting the welfare of the colonies and the Empire, were thus ignored, Her Majesty’s Government could give a subsidy to the Galway Steam Packet Company of £65,000 sterling per annum to perform a service already much better provided for, which was not only entirely indefensible, but directly inimical to the interests of Canada, whose Legislature had already subsidised a line of ocean steamers at a cost to their own revenue of £45,000 sterling per annum, and with which this Galway Packet Company would compete.

The reason of this disregard of colonial interests is sufficiently obvious. The relative merits of the two services could not have obtained a moment’s consideration. Our claim was not backed by votes in the Commons, where three millions of British North Americans have no voice or influence.

The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, of the Differential Duties in 1848, and of the Navigation Laws in 1849, swept away all protection from every colonial product except timber, which has more recently shared the same fate.

It was only in 1859 that Imperial statesmen gravely proposed to deny to Canada the right to regulate her own taxation for the purpose of raising the necessary revenue demanded by the public service. The spirited and independent manner in which Mr. Gait vindicated on that occasion the rights of the colonies will probably settle that question for the future.

Our position is ever one of uncertainty. We have no Constitution but the dicta of the ever changing occupants of Downing Street, who can only see us through the glasses furnished them by those whom accident has sent into what is regarded as the temporary exile of a colonial governorship, and whose feelings, sympathies, and interests are entirely foreign to our own. Let us cite one from among many a memorable instance of those fluctuations of opinion on matters of the most serious importance. The Government of Nova Scotia in 1857 charged two delegates, the late and the present Attorneys-General, to discuss with the British Government the grave question of a union of the colonies. The Secretary of State informed them that it was entirely a question for the consideration of the colonies themselves. In conformity with that intimation the Governor-General of Canada proposed to open a correspondence upon the subject, by which the sentiments of the different colonies might be obtained, when he was promptly informed by another Colonial Secretary that it was an Imperial question, and with a pretty significant hint that it was one which did not obtain much Imperial favour.

We do not even enjoy responsible government in the sense in which it exists in England, viz.: that of government being administered according to the well understood wishes of the people, and ever amenable to the public sentiment of the country – the great feature that exalts British institutions over those of the United States.

The systematic exclusion of colonists from gubernatorial positions must for ever prevent us from having great men. The human mind naturally adapts itself to the position it occupies. The most gigantic intellect may be dwarfed by being ‘cribbed, cabined, and confined.’ It requires a great country and great circumstances to develop great men.

British North Americans must seek in other lands than their own an opportunity of achieving greatness of any description, while as at present they are excluded from the only position in their own country worthy [of] the ambition of any man who possesses the capacity to serve the State. Regarded as occupying a position altogether insignificant by the Imperial authorities as well as surrounding nations; cut up into small and isolated communities, without common interests or facilities for mutual intercourse; destitute of broad questions of general interest to mankind, there can necessarily exist nothing but petty and personal interests to occupy their public men. Especially is this the case in these Maritime Provinces; and the effect must soon result in our institutions presenting an aspect of the most detrimental character.

One of the greatest evils that can ever befall any country is that men of character, ability, and position should withdraw from her public concerns. What have we to tempt a man possessing such advantages to engage in political life and expose himself to toil, anxiety, and all the turmoil which here attends the most ardent devotion to the interests of the State? Nothing. The highest offices we have to offer, and the largest salaries we give, afford no adequate temptation, no sufficient remuneration; while the greatest ability he can display, and the highest reputation he can achieve, will fail to open up a pathway to any distinction beyond. Nor are these provinces without significant illustrations of the unhappy effect of the misfortune to which I have adverted.

In the absence of larger questions of statesmanship which occupy more extended communities, we see men of ability, instead of aiming at lofty reputations, desecrating the talent which God has given them by fomenting sectional or sectarian discord, and placing one section or religious class in deadly antagonism with another, because the official positions to which we can aspire may thus be more readily attained.

What is it renders Britain the great and glorious Empire that she is-that gives such solidity to her institutions and such power to her name? It is to be found in the fact that she has great rewards for her sons, and thus makes the service of the State the highest ambition of her children, from the proudest duke down to the humblest commoner.

Let us now briefly turn our attention to the more difficult question: how these serious defects in our political condition, to which we have adverted, may be removed. Various are the modes which have been suggested at different periods, and a wide diversity of opinion doubtless still prevails as to what constitutional changes would be most advantageous.

The day has long since passed when the idea of annexation to our republican neighbours, or the formation of an independent republic, was entertained in any portion of these provinces. We look with mingled pride and admiration to the splendid and enduring institutions of our much-loved Mother Country coming, as they ever do, brighter and purer out of the trying ordeals which have shaken so many other nations to their foundations, prostrating governments and leaving disorder, anarchy, or despotism among their ruins.

All classes among us ardently desire that we may be in a position to strengthen the hands of the parent State and share her glories in the cause of human civilisation and progress, continuing no longer a source of weakness, but building up on this side of the Atlantic a powerful confederation which shall be in reality an integral portion of her Empire.

The Earl of Durham delineated his views on this subject twenty years ago in that enduring monument of his perspicuous statesmanship – his Report on the affairs of British North America. With great ability he there adopted and extended the views propounded so early as 1814 by His Royal Highness the late Duke of Kent, urging the importance of a legislative union of these colonies.

The same principle was ably elaborated in the Assembly of Nova Scotia a few years ago by Mr. Johnstone; and Mr. P. S. Hamilton made it the subject of a very interesting pamphlet in 1855, and more recently brought it under the notice of his Grace the Duke of Newcastle in a more condensed form. Mr. Howe, it is well known, has advocated, with great force and ability, representation for these colonies in the Imperial Parliament; and has urged with his usual vigour and eloquence the advantage of turning to account the information of colonial statesmen, both by appointing them to preside over the colonies and to aid in their management in subordinate offices in Downing Street.

In Canada, besides the various occasions on which it has been discussed by many of her public men, a project for the federal union of these colonies was proposed to the Legislature in 1858 by that eminent Minister of Finance of the Canadian Government, Mr. Galt, and was subsequently warmly sustained in an able State paper addressed by that gentleman, Mr. Cartier, the Premier of the Canadian Administration, and Mr. Ross, the President of the Executive Council, to the Colonial Secretary. Mr. George Brown, the former leader of the Opposition in Canada, Mr. J. S. Macdonald, and many other Canadian statesmen, have again and again committed themselves to the same views. In 1859 it obtained the eloquent advocacy of the accomplished T. Darcy McGee, one of the members for Montreal, who made it the subject of a forcible address to the Legislature.

On one point, however, whatever may be the form it may assume, the general opinion seems to be in favour of the grand principle of union. Some advantage would doubtless ensue from representation in the Imperial Parliament, but that, I conceive, would not be acceptable to the people of these provinces in the only way it could be obtained – accompanied by the taxation borne by those who are thus represented. To occupy the invidious position of sitting in the Commons and speaking on matters of colonial import, but denied the right to vote, would be objectionable to any independent mind, and would be unattended with any substantial advantage.

Little doubt can be entertained that the selection of colonial governors from among colonists would be followed by highly beneficial results. A career of honourable distinction would thus be opened up which would at the same time attract the services of those who are most capable of serving the State, and ensure due regard to a high-minded and honourable political course of action as most likely to obtain the favour of the Crown, while it secured the confidence of the inhabitants generally throughout the colonies. The temptation to obtain immediate and temporary success at the sacrifice of broad principles would be thus materially diminished. The advantage which would arise from the conviction on the minds of the leading public men in all the provinces that the able discharge of the duties of their respective offices might lead to their elevation to a position affording some adequate reward, and attended by honourable distinction, could hardly be overestimated in its immediate operation upon the condition of the country.

It would be an insult to the leading men in British North America to inquire whether she possesses those equally well qualified for the position of colonial governors with any that are likely to come from abroad. Infinitely better acquainted with the country and the character of the people – and dependent for their promotion not upon the adventitious circumstances of birth or parliamentary connections and influence in England – the people would have a much better assurance than at present that their wishes and interests would be regarded. And why should we be called upon to sustain this brand of inferiority upon ourselves at so great a cost both pecuniary and otherwise? The highest salary paid to a departmental officer in Nova Scotia is $2,800; in New Brunswick, $2,600; while we are called upon in each province to pay a gentleman from England-who performs duties not a tithe as arduous as those devolved upon other officials – no less than $15,000 a year as salary, and to contribute a large additional amount towards maintaining his establishment.

Another important point in connection with this part of our subject, far transcending in importance any question of the amount of salary, is the security which would thus be afforded that in cases of appeal to the Mother Country and appeals there must be so long as governors are only amendable to Imperial authority-when the governor, in the exercise of his prerogative, acts unconstitutionally and in opposition to the wishes of the people, justice would be done impartially, and a constitutional decision given, which would not be open to the imputation of party bias from the recollection of past services, or the claims or influence of friends in either the Lords or Commons. This one change in our colonial system would give new life and vigour to our institutions, upon which, under existing circumstances, many have ceased to look hopefully.

The more important consideration, undoubtedly, is the union of the provinces. It would be premature to decide definitely on any particular plan by which that might be accomplished until the subject is discussed – as discussed it must be, and that at no distant date – by the leading men of all these provinces, and of all parties, in conclave.

The desirability of the union in any form being once arrived at, there is little reason to doubt that it could be arranged in a manner satisfactory to all sections of the confederation, and giving to the whole the advantages of the highest character not now enjoyed, while it would not materially detract from any privileges of a local character at present in their possession.

Without, therefore, entering further at present upon details which it seems premature to discuss, it only remains for us to notice some of the more prominent results likely to flow from a union of the provinces.

It would give us nationality. Instead of being Newfoundlanders, Nova Scotians, Prince Edward Islanders, New Brunswickers, and Canadians, often confounded abroad with the inhabitants of Nova Zembla and similarly favoured regions, we should be universally known as British Americans, occupying a country of vast extent, with a soil of unusual fertility, and rich in all the natural resources and mineral productions which have made Britain the emporium of commerce and manufactures for the world.

Instead of being divided by petty jealousies, as at present, and legislating against each other, with five hostile tariffs, five different currencies, and our postal communications under the control of five different departments, we should, drawn together by a common interest and with a common system of jurisprudence, obtain that unity of action which is essential to progress. No part of the known world is better adapted for such union, so little antagonistic in point of local interests, as the different parts of British America. Nor could these interests be materially compromised by any legislation. Take Halifax and St. John, for instance, in both of which places it has been the endeavour of little minds to excite a mutual jealousy. Nature has placed Halifax in the most advantageous position for communication with the European world; but she has not located her harbour at the mouth of a magnificent artery of communication such as St. John can boast, with a fertile country immediately contiguous. Nova Scotia possesses coal fields of unrivalled extent and value; yet she has but a tithe of the fertile ungranted lands with which New Brunswick invites the immigrant to make her country his home.

No legislation can materially disturb these immense natural yet diverse advantages which Providence has bountifully bestowed on each; but, divided by mutual distrust and jealousy, we may each seriously retard the common interests and advancement of two provinces which, together with Prince Edward Island, ought now to be united in one legislative union.

The same principle applies to the whole. While Canada was exporting bread stuffs to the amount of nine millions of dollars in 1857, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were importing over two millions of the same article. In the same year, while these two provinces imported from the West Indies nearly two millions in exchange for our exports to those islands, Canada imported from the same quarter to the amount of four and a half millions of dollars without having anything to send in return. While Nova Scotia exports an enormous amount of coal to the United States, probably not much if at all under three hundred thousand tons this year, Canada depends on importation for the same article.

Union will give us broader questions of a character infinitely more elevated than those which at present divide our public men.

The want of such a field has exercised a most baneful and pernicious influence in these colonies, where we too often see public men of undoubted ability, instead of being engaged in the discussion of great principles and patriotically emulating each other in the promotion of enlarged views, by which the prosperity of their country might be increased, and rivalling each other in the onward path of progress, stooping to the despicable and demoralising expedient of advocating their own personal ends and immediate interests by exciting a war of creeds or nationalities, where it should be the pride of every man to sustain unsullied the glorious principles of civil and religious equality – principles upon the maintenance of which depends to a large extent the future greatness of British America.

There is another question which has recently been pressed upon our attention which deserves a passing notice – the local defence of these colonies. Canada, it is true, has annually expended about one hundred thousand dollars for that purpose, and recently a general movement has been made to wipe out the provincial disgrace that in these lower colonies no means of local defence existed.

Stimulated by the great Volunteer movement in Britain, and the possibility that the day was not distant when our services would be needed, a considerable body of riflemen has been organised. All our experience, however, tells us that, except in connection with some movement of a national character, it will be almost impossible to sustain the interest in a question even so important as this is in every respect. That British North America has the ability to bring into the field at no distant day an able body of trained and effective men, to defend her interests in time of peril and, what is equally necessary, sustain in time of peace that feeling of self-reliance essential to the formation of national character, cannot be doubted. The enthusiasm with which thousands have rushed forward at the first faint call, and the proficiency of the Volunteer corps which in so brief a period has attracted the admiration of distinguished soldiers who have visited us, is conclusive on that point. The martial courage and military talent of our sons will not be questioned while we can point with pride to the heights of Alma, the plains of Inkerman, the terrible Redan, where, foremost among the first, their blood was shed; even though in the beleaguered fortresses of Kars and Lucknow we had not given England generals who sustained her military glory in the hour of need.

Those not immediately engaged in it can hardly appreciate the sacrifice of time and money demanded of those who have enlisted themselves in this arduous undertaking; and it requires neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet to foretell its rapid decline, unless sustained with enthusiasm and liberality by the wealth and intelligence of the country, comprising all parties.

No patronage or aid from any or all of these sources will for a moment compare with imparting to such a body of men a national character, and devolving upon them national duties and responsibilities.

If anyone doubts the ability of a country possessing the population and resources of British America to raise an effective arm of defence, let them but examine the history of Sardinia, Switzerland, or the United States during their struggle for independence, and their misgivings must be speedily dispelled.

Then, instead of being, as at present, a source of weakness to the parent State, we should, like vigorous offshoots, nourish and sustain her in any hour of need.

The Union of the Colonies, as a question of political economy, is not unworthy of consideration. A similarity in our tariffs with colonial free trade, would at the same time afford us mutual advantages and protection, and relieve us from a large portion of the expense now attendant upon the collection of the revenue. In Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island – three provinces that might, with much greater advantage to each other in every respect, be comprised under one government – thirty-six thousand dollars per annum are expended in the salaries of governors alone, and over one hundred thousand dollars in legislative expenses every session. Including Canada and Newfoundland, the former cost over eighty thousand dollars, and the latter between seven hundred and eight hundred thousand dollars.

It must be apparent to everybody at all acquainted with our condition, that the expenditure of this large amount of money is counterbalanced by no adequate return, and that, by a unity of interests, results much more beneficial might be obtained, together with a largely diminished expenditure.

Take, again, the vitally important question of intercommunication, and the necessity of union and concerted action becomes still more apparent. Destitute of such concert, in an evil hour for the interests of these provinces the Government of Nova Scotia refused to co-operate in the arrangements made by Canada and New Brunswick, which, if not thus frustrated, would ere this have given us an unbroken line of railway from Halifax through New Brunswick to the western limits of Canada, affording us at the same time communication with the twenty thousand miles of railway in the United States. Thus foiled in carrying out the magnificent project in which they were engaged, the Grand Trunk Company were obliged to seek an Atlantic outlet for the vast products of Canada through a foreign State and compelled to lease the line to Portland. What has been the result? Nova Scotia has expended nearly five millions of dollars in the construction of railways, which, local and isolated in their character, afford neither stimulus to her trade nor intercourse with her neighbours, while for many years to come her revenue must be largely taxed to meet the payment of the interest on the debt thus created.

The position of New Brunswick is but little better, although, perhaps, not quite so discouraging. Canada, notwithstanding the investment by the Government of more than twenty millions of dollars, occupies the precarious and dependent position of having her whole trade for a large portion of the year subject to the caprice of a rival and not always very friendly power.

Much as the British Government is to blame for allowing such a state of things to continue, and blindly as they have refused to regard the great Imperial interests involved, the neglect of which may at any moment require an outlay on their part infinitely greater than any aid required to have accomplished this work, no one can for a moment suppose it could have existed had any tie united these colonies with a common bond.

It is to be hoped that the folly of expecting any large results from local and isolated railways is already fully demonstrated to both Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and that it has now become a first consideration with them to direct their attention to the means by which both may be relieved from the consequences of a large debt, incurred for works not only unproductive of any directly remunerative results but also unattended by any substantial advantage to our trade or commercial importance. The conviction must have forced itself upon the public mind that we must extricate ourselves from these difficulties by obtaining connection with the railways of Canada and the United States by one or other of the routes proposed. Much has already been done towards achieving that result. The three colonies most deeply interested have not only jointly pressed a common scheme on the attention of the British Government, convincing the Derby Administration of its importance, but also enlisted the support of a large number of public men and commercial communities in the enterprise, resulting in the application to Parliament of the Boards of Trade of Liverpool and Glasgow, and other influential bodies, to carry out the scheme proposed by the Colonial Delegation of 1858.

The visit of the Prince of Wales and the eminent men who composed the suite of His Royal Highness must have impressed them forcibly with the necessity and importance of an intercolonial railway – a work in which the Duke of Newcastle took a deep interest when Secretary for the Colonies on a former occasion.

Canada having completed the line from Quebec to Rivière du Loup; Nova Scotia, from Halifax to Truro; and New Brunswick, nearly a hundred miles of the line through this province – if the St. John Valley route or the St. Andrews and Quebec be adopted a comparatively small outlay would complete the communication. The extent of the work is much reduced; the Government of Britain and the British public are interested to an extent that, with the experience of the past few months, cannot fail to convince the most sceptical; the necessities of these lower provinces invite our hearty co-operation; while the difficulties in which the Grand Trunk is involved will but render the Canadian Government and the shareholders on both sides the Atlantic more anxious than before to carry out the original enterprise.

The night of darkness that now enshrouds the prospects of these colonies in connection with their railway operations will be but the harbinger of a bright and glorious morning of advancement and prosperity; and in a brief period we shall possess a continuous line, extending from Halifax to Windsor opposite Detroit, and by the American line some four hundred miles beyond that point, through Wisconsin and Illinois, to the frontier of Iowa.

The limited time at our disposal has only permitted me to notice in passing a few of the results likely to flow from a union of the colonies, and I fear that I have already trespassed too largely upon your kind indulgence. Permit me, therefore, in closing, to remind you that the advantage which would result from such a union is not a matter of opinion, as it has already been demonstrated by the union between Upper and Lower Canada.

Let us, then, extend the same wholesome principle – uniting our common interests and consolidating the whole by strengthening each other.

Possessing as we do the healthiest climate in the world, with an immense area of fertile soil, and abounding in the richest mineral resources, all we require are wise political arrangements to attract population, capital and skill.

Our climate is more healthy than that of England; the fertility of the soil is unsurpassed by her; our geographical position relative to the New World is the same as she occupies to the Old; our equally magnificent harbours present the same facilities for commerce; while the iron and coal, and the limestone – the possession of which has rendered her the greatest manufacturing mart of Europe – here abound to any extent in close proximity and of the most excellent quality. Who can doubt that under these circumstances, with such a confederation as these five provinces – to which, at a future day, the great Red River and Saskatchewan country, now in possession of the Hudson Bay Company, and British Columbia, on the Pacific coast, would be added – as would give us the political position due to our extent of area, our resources, and our intelligent population – untrammelled either by slavery or the ascendency of any dominant Church – presenting almost the only country where the great principles of civil and religious equality really exist, British America, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, would in a few years exhibit to the world a great and powerful organisation, with British institutions, British sympathies, and British feelings, bound indissolubly to the Throne of England by a community of interests, and united to it by the Viceroyalty of one of the promising sons of our beloved Queen, whose virtues have enthroned her in the hearts of her subjects in every section of an Empire upon which the sun never sets?

This speech is from Rt. Hon Sir Charles Tupper, Recollections of Sixty Years (London: Cassell and Company, Ltd, 1914), pp. 14-38.