This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Aaron Wudrick, March 13, 2024

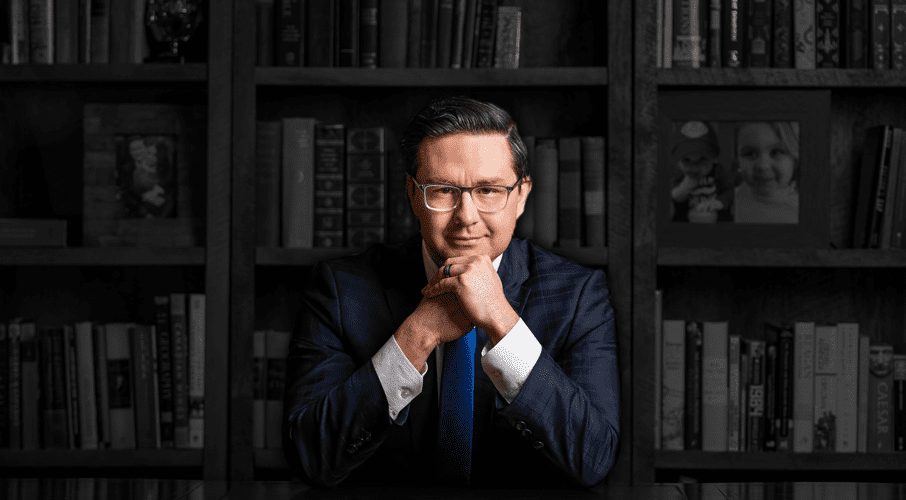

In a speech to the Greater Vancouver Board of Trade last Friday, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre let it be known that he loves “free enterprise,” but has little time for “corporate lobbyists,” going so far as to lambaste them as “utterly useless in advancing any common sense interests for the people on the ground.”

To many observers, this may seem contradictory. How can one be supportive of business, but oppose lobbyists acting on their behalf? How can one claim to be a fan of free enterprise, while in the next sentence attacking large swathes of the business community as having “no backbone and no courage”?

To understand where Poilievre is coming from, look no further than an open letter that was published last week and signed by the CEOs from some of Canada’s largest companies. It calls on the country’s finance ministers to create new rules to “encourage” Canadian pension funds to invest more in Canadian businesses.

These CEOs are upset because nearly two decades ago, Canada removed rules that limited Canadian pension funds from investing more than 30 per cent of their assets overseas. Ever since, pension funds’ interest in publicly traded Canadian companies has plummeted — dropping from 28 per cent in 2000 to just four per cent at the end of last year.

It turns out that large institutional investors looking for better returns to fund retirees’ pensions can do much better outside of Canada than within. And while it makes perfect sense for Canadian CEOs to be alarmed by this, their diagnosis of the problem and prescription for how to fix it illustrates the difference between a free enterprise and a corporatist mindset.

A supporter of free enterprise looks at the weak appeal of investing in Canadian businesses and asks questions like: What is it about many Canadian companies that makes them so unappealing to invest in? What changes could governments make to ensure businesses become more productive and more profitable? Are taxes too high? Is regulation too excessive?

It’s an exercise in looking at more successful businesses elsewhere and trying to figure out what needs to change at home, in order to allow Canadian businesses to succeed.

The corporatist, by contrast, is uninterested in such thought experiments. The only relevant consideration for corporatists is how to pad their own bottom lines. They’re ambivalent about whether the money comes from paying customers, or taxpayer subsidies.

Telling governments that they need to cut taxes or streamline regulation might get some minister’s nose out of joint. It’s so much easier to take a cheque or whisper in the government’s ear that it should rig the rules to discourage investors from putting their money where they prefer.

The fact that Poilievre — unlike Prime Minister Justin Trudeau — is even willing to draw a distinction between these two very different mindsets is notable, and refreshing. For far too long, policymakers in Canada have conflated these two camps and treated them as one homogeneous blob — as if a business desperate for the government to just get out of the way and let it do business is the same as one that deploys a phalanx of lobbyists to Ottawa to queue up at various government wickets looking for handouts.

The rebuttal from some of these sad-sack corporate beggars might be: don’t hate the player, hate the game. And they’d have a point. For decades, at both the federal and provincial level, governments of all political stripes have overseen a massive proliferation of subsidy programs and state intervention, of which the $40 billion in taxpayer lolly for electric vehicle batteries is only the latest and most eye-watering example.

But the reality is, when there are free handouts on offer, what business is going to say no — especially when a competitor might not? Our governments are directly responsible for creating this culture of business dependency, and they will have to be the ones to wean companies off of it.

If he means what he says, Poilievre will have his work cut out for him as prime minister. Panicked, coddled, rent-seeking corporatists won’t go quietly into the night. But maybe, just maybe, if those in the business community who have real confidence in Canadian businesses and the ambition to take on the world can find their backbone and their courage, free enterprise in Canada might stand a fighting chance.

Aaron Wudrick is the director of the domestic policy program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.