By Sergey Sukhankin

March 22, 2024

Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has delivered plenty of surprises. From a military point of view, very few experts expected the Armed Forces of Ukraine – underfinanced and lacking modern, sophisticated arms and equipment – to be able to withstand Russia’s initial offensive and later liberate large part of the country.

The economics of the war was no less remarkable. For instance, Russia was astonished by actions of the “collective West” – and the European Union, in particular – when comprehensive, although still imperfect, economic sanctions were introduced and then progressively strengthened.

The West in turn is still coping with the fact that the Russian economy – which former United States President Barack Obama declared was “in tatters” in 2015 – still somehow manages to stay afloat (Chang 2017) while financing the war.

Arguably, the biggest surprise of all is the performance of Russia’s hydrocarbons sector. Exceptionally promising before the war, it was expected to collapse under the pressure of sanctions in 2022. Yet in 2024 it is not only still functioning – though suffering notable losses (Babanova 2023) – but also fuelling Russia’s war machine.

Despite some tactical successes and ability to withstand external pressure, strategically – if current reality does not change drastically – Russia’s hydrocarbons sector may be staring at a bleak future. In the meantime, this and growing geopolitical instability (Derhally 2024) in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region create a historical opportunity for Canada’s energy sector.

Russia’s oil sector: the noose is growing tighter

Prior to the outbreak of its large-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s oil sector had a bright future. Abundant resources, promising logistics, and the relative cheapness of production fuelled interest of foreign buyers from Europe and Asia. In 2021 (Heussaff et al. 2024), the last year before major economic sanctions, Russia produced 540 million tons of crude oil (13 percent of global production) with 260 million tons exported directly as crude oil (13 percent of global exports); this made Russia the second-largest oil producer in the world (Rosstat 2022), behind only the US.

However, Russia’s reckless aggression, and overarching confidence in its indispensability to the EU, has hurt its oil sector – and the pain will likely worsen in the future. In 2022–23, Russia’s oil industry experienced only a slight decline – seeing a 1 percent drop in production (Novak 2024) and an export reduction of around 500,000 barrels per day. Russia’s budget revenue may have dropped by 15 percent (Itskhoki 2023) because of oil-related sanctions and restrictions – but neither the Russian budget nor its oil sector have collapsed. Indeed, Russia’s economic resilience has prompted some experts to say that “sanctions are not working” (TASS 2024).

So how has Russia’s oil sector managed to avoid financial ruin? For three key reasons: First, in 2022–23 world prices of oil not only remained high by global standards, but they also remained much higher than required for Russia’s state budget to break even. The oil price bonanza has helped to fuel Russia’s war against Ukraine, while also allowing it to maintain its domestic social programs.

Second, Russia has been selling some of its oil at a discount (Financial Times 2023) to its foreign partners. Opinions vary on how much Russia reduced its prices, but it is known that Russian oil was still trading above US$60 per barrel – lower than the pricing point offered by other oil producers, but high enough for the Russian budget to break even. Russia’s key customers include India (70 million tons) (YouTube 2023), whose imports of Russian oil skyrocketed (Neftegaz 2024a) and China (Interfax 2024), whose imports reached 107 million tons. India and China’s thirst for Russian oil has gifted President Vladimir Putin with surpluses in trade and cash inflow. Moreover, India has reportedly resumed purchasing Russia Sokol oil (Neftegaz 2024b) after a two-month hiatus.

Third, Russia has violated an oil price cap (Sonnenfeld and Tlan 2022) imposed on Russian oil by G7 nations and the European Union. Russia has managed this by exporting oil through a “shadow fleet” of Greek tankers (Neft kapital 2023), thereby evading international restrictions and formal requirements. The oil price cap was punishment for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Under the price cap, the G7 and EU nations agreed to not buy Russian oil at a price above US$60 per barrel. At the time of the price cap’s implementation, around 90 percent (Johnson, Rachel, and Wolfram 2023) of Russian oil was being exported to Western consumers or companies. By refusing to pay market prices for Russian oil, the allies hoped to significantly impact the Russian budget and impair Russia’s ability to finance the war in Ukraine. The trouble is, the price-cap pledge only applied to signatories of the measure – there was no effective punitive mechanism to apply to other parties that chose to pay market prices for Russian oil.

Ultimately, the oil price cap has ended up being simply “a Western measure against Russia,” lacking the global support necessary for it to be effective (Gilchrist 2022).

The price cap has turned out to have yet more flaws: some signatories have since refused to follow its main principles. Greece is the world’s largest oiltanker-owning nation, with between 400 and 600 vessels. The Mediterranean country established a parallel scheme for transporting Russian oil to end users primarily in India and China as well to commodity traders in Singapore and countries of the Persian Gulf Region. Some experts have argued that the use of this scheme allows Russia to sell its oil to Turkey, Latin American nations, and even countries in North Africa (Golos Ameriki 2024). According to some 2023 estimates, Greek tankers carried between 20 to 45 percent of all Russia’s oil shipments with next-to-no-consequences (Sankranti 2023). In addition, countries such as Malta and Cyprus have been suspected of also taking part in the “shadow fleet” scheme (Gavin 2023).

Exacerbating the situation, the marginal cost of extracting Russian oil – estimated to be around US$10 to US$20 per barrel – further undermined the effectiveness of the allies’ oil price cap. The irony is some allied nations had urged for an even tougher price cap on Russian oil – but were ignored. For instance, Poland suggested a price cap of around US$30 per barrel – but they failed to find support for the tougher sanction (Ria Novosti 2022).

Meanwhile, some EU countries, including Czechia (4.2 million tons), Hungary (5 million tons), Slovakia (5 million tons) and Bulgaria (discontinued buying Russian oil since March 2024) – were allowed to purchase the Russian oil after 2022 because of the strategic dependency of their economies on external (Russian) hydrocarbons.

All in all, Russia to date has managed to largely evade the full brunt of sanctions against its oil sector. But things going forward may not be so rosy for Russia. Its oil sector faces several challenges that will be rather hard to resolve – specifically, the fear of secondary sanctions has had a de-motivating impact on the Greeks. As a result, both Russian and Western experts are now talking about the nearing demise (Braslavskiy 2024) of the “shadow fleet” that played such an indispensable role in boosting Russia’s coffers (The Insider 2024). Recently 50 large Greek tankers were sanctioned by the US, including YasaGolden Bosphorus, SCF Primorye, Kazan, Ligovsky Prospect, NS Century, NS Champion, Viktor Bakaev, and HS Atlantica. The US also sanctioned Sun Ship Management (which manages oil tankers belonging to Sovkomflot), Hennesea Holdings Ltd. (based in the UAE), and NS Leader Shipping Incorporated (registered in Liberia) that have been accused helping Russia to evade oil-related restrictions. While the prospect of complete demise of this sanctions-evading mechanism may be an overstatement (@ TankerTrackers 2024), since Russian businesses will likely be able to adapt to some extent, Russia’s ability to continue using this (and similar) types of counter-sanctions mechanisms is bound to be eroded.

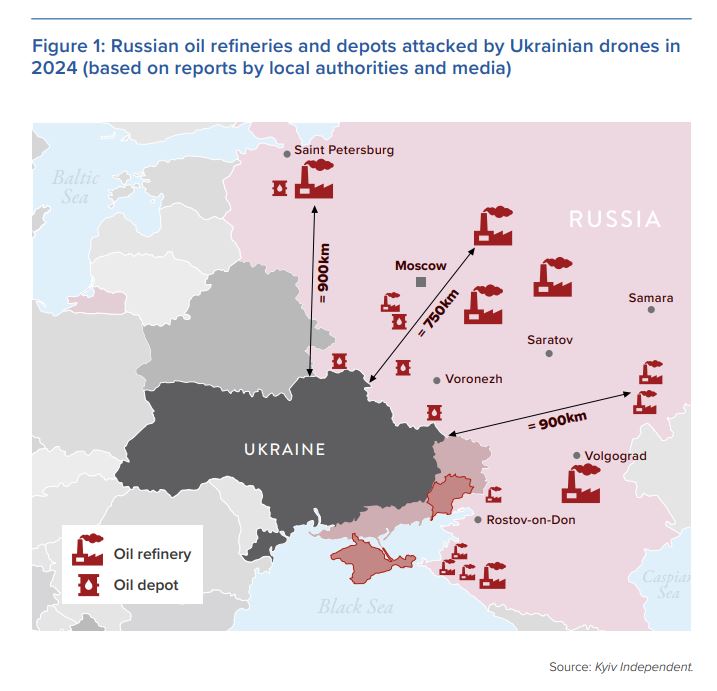

Another key problem for Russia going forward is the impact of Ukrainian kamikaze drone attacks on Russian critical oil infrastructure (Kossov 2024). Since the new year, there have been several attacks, including:

- An attempted attack at a Saint Petersburg oil terminal on January 18.

- Two attacks on the Klintsy-based (Briansk) oil terminal, on January 19 and 20.

- An attack on an oil terminal in Ust-Luga (Leningrad oblast) on January 21.

- An attack on oil refinery at Tuapse (Krasodar krai) on January 25. An attempt to attack Kstovo-based (Nizhny Novgorod) Lukoil-owned oil refinery on January 31.

Following these attacks, Ukrainian forces delivered a series of powerful blows against Russia’s critical oil infrastructure between February 12–14 (Glavnoye in UA 2024), demonstrating their determination to continue targeting this sector of the Russian economy that is critical for the ability of the Russian side to conduct war.

For obvious reasons Russia has not provided specific details about the actual damage during the Ukrainian attacks. However, the fact that Russia has now declared a six-month ban on exports of benzene suggests that these attacks have hurt Russia’s ability to refine oil and produce various oil products (RBK 2024).

Reports also suggest that the attacks have caused a notable decrease in transportation of oil through the Baltic, Black, and Azov Seas, as well as via the Arctic (Moscow Times 2024a) and destroyed both critical infrastructure as well as large quantities of oil and oil products. Recent reports have speculated that more than 10 percent of oil refining capacity has been damaged in the Russian Federation as a direct result of Ukraine’s attacks.

Prominent Russian oil expert Sergey Vakulenko has downplayed the attacks, saying their largest impact has psychological, by striking a blow against Russian morale (Abishev 2024). However, if Ukraine continues to use drone attacks with the same intensity, it will certainly grow into a more serious problem for Russia.

These challenges, tactical in nature, are overshaded by one strategic problem: large investors – both at state and corporate levels – shy away from committing to large and expensive strategic projects in Russia. Perhaps, the best example is the Arctic-based Vostok Oil megaproject (Sukhankin 2024a), which Russia promised would drive greater economic growth (Vedomosti 2023). Today, foreign stakeholders, including some that are allegedly friendly to Russia and China, have halted their participation in the project. The same situation is unfolding at Russia’s Arctic LNG-2 megaproject, which will be discussed later in the commentary.

Russia’s oil industry did seem to have a window of opportunity – cooperation with foreign partners, specifically in sub-Saharan Africa. Russian energy companies were strategically interested in participation in large oil projects and construction of oil refining facilities in such countries as Uganda, Sudan, Algeria, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Cameroon, Gabon, Chad, Angola, the Republic of Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Ugandan projects are of special interest to the Russians due to an agreement that apparently arose out of a personal meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ugandan President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni during the July 2023 Russia-Africa Summit and Economic Forum in Saint Petersburg. Following the meeting, the Ugandan leader stated that Russian companies working in the realm of oil extraction would be welcomed in oil projects in his country. Interestingly, Russia forged the oil-related deal via intensification of arms/weaponry supply to Uganda, expecting that Russian companies will be playing a crucial role in Uganda’s growing oil sector. For now, however, the prospects of many of these partnerships appear to be uncertain (Parshynova 2024); for instance, negotiations between Russian interests and their Ugandan partners are still taking place.

The US and the EU have both committed to tightening economic sanctions against Russia as well as parties that assist Moscow in evading them. While that might lead one to presume that Russia’s oil sector will continue to gradually recede, it doesn’t mean that it is bound to collapse – there are enough parties in the world eager to buy Russian oil on the cheap – but its effectiveness and efficiency will likely seriously diminish.

Furthermore, Russia’s war in Ukraine and the resultant discontinuation of ties with economically sustainable countries with strategic interests in Russian oil – primarily, the EU, Japan, South Korea, and India – coupled with China’s reluctance to commit to investments in Russia’s new Arctic oil project, and growing competition from other oil exporting nations, will likely take a toll on Russia’s oil industry.

Russian (L)NG ambitions are eroded by war and sanctions

Before the war against Ukraine, Russia’s natural gas industry played a central role in the EU’s energy mix, while also serving customers in China, Turkey, and Central Asia. The war, however, introduced drastic changes. A combination of restrictions on transit (not economic sanctions) and the September 26, 2022, destruction of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline after a series of underwater explosions – most likely, a sabotage by unknown perpetrators – resulted in the shrinking of Russia’s export of pipeline natural gas to the EU (Alifirova 2024) from an overwhelming 40 percent (2021) to a mere 8 percent (2023).

To mitigate the humiliation of the de facto loss of the European market, Russian political leadership tried to promote a narrative about the Chinese market becoming a perfect substitute – much more promising than the EU.

This information, however, is far from truth. Despite Putin’s personal advocacy (Moscow Times 2024b), Beijing refused to increase the amount of imported Russian natural gas, and deflected questions about its participation in the construction of the Power of Siberia-2 (a.k.a. Altai gas pipeline) project. This project – its original story dates back to 2006 – was expected to strengthen Russia’s position as a key supplier of natural gas to the Chinese market, with annual exports of some 50 billion cubic metres annually.

After 2022, Russia’s strategic interest in accomplishing the megaproject grew exponentially (Pao 2024) – mainly due to the lack of financial means for meeting the demands of war and satisfying domestic needs – but Beijing took a much more reserved approach, taking time and measuring its options given Russia’s growing (to an extent even overarching) reliance on China (Pipeline Journal 2023). Instead, Chinese sources argue that the Chinese side – clearly understanding how cornered and isolated Russia is – not only opposes the idea of splitting costs for the Power of Siberia-2 but is also demanding new discounts for Russian natural gas (Wong 2023). Indeed, while Russian sources report beating one record after another – in terms of delivery of natural gas to China via the Power of Siberia-1 – the exact terms and the actual quantities delivered may not correspond to Russia’s official data (Chizhevskiy 2024).

Moreover, to avoid the EU’s mistakes in dealing with Russia, China has signed new contracts with Qatar – one of the top-three global producers of LNG – to diversify imports of natural gas (Ratcliffe and Ahmed 2024). In general, China mainly imports natural gas (both pipeline and LNG) from nine countries. It is unlikely that China will want to abandon this diversity of supply and instead prioritize a single supplier.

Interestingly, Russia continues to boast about its invulnerability to collapsing natural gas exports to the EU while admitting to notable losses in net profits (Financial Times 2024). President Putin, meanwhile, has hinted to German authorities that Russia could easily renew supplies of natural gas through Nord Stream-1 “within one week” – if Berlin is interested (Lenta 2024). Yet, to Russia’s disappointment, major EU natural gas consumers do not seem to be interested in a return to “business as usual” any time soon.

Russia is likely pinning its hopes on an eventual return to EU markets via a new natural gas hub in Turkey (Ria Novosti 2022) with an expected capacity of 35.7 billion cubic metres per year (Sukhankin 2021). Given Turkey’s evasive position, the EU’s growing ability to diversify its gas imports, and other geopolitical factors, the future of this project – and specifically Russia’s part in it – is unclear.

In the meantime, Russia’s ambitious plans to develop its LNG industry are now in jeopardy thanks to the Kremlin’s reckless geopolitical aggression.

Prior to the attack on Ukraine, Russia planned to harness the huge resources of the Arctic region and corresponding logistical routes (primarily, the Northen Sea Route) to become one of the world’s top LNG producers with a 20 percent share in the global LNG industry by 2035. Russia expected both EU and Indo-Pacific actors (India was named as one of the markets with most promising potential) to become end users of Russia’s LNG (Sukhankin 2021).

A prime example of Russia’s global ambitions for LNG exports is the NOVATEK-owned Arctic LNG-2 megaproject (Novatek 2024). Located in the Gydan Peninsula (Yamal Nenets Autonomous District), on the Siberian coast, this project attracted such investors as France’s TotalEnergies, China National Petroleum Corporation, China National Offshore Corporation, Japan’s Mitsui & Co. Ltd., and Japan Oil, Gas, and Metals and Energy National Corporation. However, after the United States sanctioned Russia in early November 2023 foreign actors were forced to reconsider their participation in the megaproject (Sukhankin 2024b), halting – and, potentially, terminating – their presence in the initiative.

Obviously, this does not mean the end of the project as such, but it will compromise Russia’s ability to sell LNG at a comfortable price. Another challenge facing Russia is its lack of specially designed LNG carriers (Arc7) for use in Arctic conditions (Parshynova 2023). These ships are mainly produced in two places – in South Korea, which is unwilling to work with Russia due to concerns over sanctions, and China, whose shipyards are overwhelmed with already existing contracts.

Offering Russia a ray of hope is US President Joseph Biden’s decision to temporarily pause construction of LNG export terminals. Biden’s decision is seen by Russian experts (as well as by some close-to-Kremlin Europeans) as a good sign: if the EU’s energy security is jeopardized, it might convince Brussels (or individual EU nations) to accept Russian LNG (Sukhankin 2024c). However, mainstream EU experts don’t currently share Russia’s optimism. Another opportunity for Russia is non-compliance (Meduza 2024) of some EUbased companies – especially from Italy, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain – that, using China as a middleman, were supplying essential equipment for Russia for the development of the Arctic LNG-2 project. However, if Russia continues its aggression against Ukraine many partners and end-users of its LNG would find it increasingly risky to deal with Russia.

Thus, if the current status quo holds, Russia’s strategies for pipeline natural gas and LNG will most certainly be hampered due to international sanctions and restrictions.

Russia’s blunders provide a chance that neither Canada nor its partners should miss

Russia’s conventional energy sector has suffered serious self-inflicted wounds.

Meanwhile, Canada – a global superpower when it comes to hydrocarbons, ranked third in proven oil (Data Pandas 2024) and second in natural gas reserves (Canadian Gas Association 2024) – has a host of virtually unbeatable competitive advantages.

First, it is incredibly reliable. Unlike Russia – or suppliers from the MENA region – Canada has a stable economic and political environment and is known for peaceful and predictable foreign policy. A free market economy, Canada also shares the same set of democratic values and principles with its strategic partners in Europe and in Asia.

Canada’s foreign partners do not have any probable cause to worry that Ottawa will use the country’s natural resources as a tool of geopolitical pressure or blackmail. The same can’t be said of Russia or of hydrocarbon-exporting MENA nations. A case in point: In 2022, Russia gloated about its ability to “freeze Europe” if European countries dared to try to thwart its military ambitions in Ukraine. Given the current turmoil in the Middle East, and Russia’s continued aggressive behavior in Europe – including a potential new conflict with Moldova and, possibly, beyond – these regions are simply not reliable sources of hydrocarbons. For hydrocarbon importers, Canada is the best bet in terms of longer-term energy security.

The second advantage Canada holds relates to the security of its supply chain. World Economic Forum (WEF) experts noted more than 80 attacks on transport and commercial vessels between November 19, 2023, to February 9, 2024, in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. These attacks have seriously jeopardized transportation via this strategic transportation artery, and especially threatens transportation of LNG and oil. As pointed out by Julia Nesheiwat (a distinguished fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center), “Every day, it becomes likelier that there will be an escalation of conflict in the Middle East, particularly between Hezbollah and Israel […] the global supply of oil and gas due to trade disruptions not only in the Gulf, but also via the drought-affected Panama Canal […] Countries would be left scrambling and forced to turn to reliable production in the United States, Canada, and Mexico” (Nesheiwat 2024). For hydrocarbon importers in the Indo-Pacific region (included imports of blue hydrogen), Canada offers direct and secure access.

Finally, Canada holds an advantage due to its compliance with international law. There is no reason to believe that the Putin regime, or its eventual successors, will make a major transition into a true democracy. Thus, for the foreseeable future, Russia will remain among the most sanctioned nations in the world – especially if its war in Ukraine continues, or if it extends its military aggression to other countries.

For would-be customers of Russian hydrocarbons, they will need to navigate the growing legal morass or else risk being hit with secondary sanctions of their own. This danger extends to parties who might be tempted to collaborate with Russia on new technologies or share expertise essential for modernizing their own domestic oil and natural gas sectors. This is especially a concern for countries in the so-called Global South that might see Russian know-how and technologies as instrumental to achieving and preserving high levels of economic growth – often a key condition for attracting foreign direct investment.

As a global leader in technologies that both lower operational costs and reduce carbon emissions, Canada is a much more attractive partner than Russia, which, for instance, has an abominable track record of environmental violations at its oil and gas producing sites in the Arctic.

In the final analysis, I must stress that it is not only in Canada’s interest but also in the interests of its allies and partners – both in Europe and especially the Indo-Pacific region – that Canada establishes itself as a secure and trustworthy substitute to Russia as the world’s key supplier of energy resources and corresponding technologies. Russia has proven to be an unreliable and dangerous actor who is willing to put at risk global energy security and sacrifice long-term relations with its strategic partners for the sake of its illusory geopolitical objectives and nineteenth century neo-imperialist ambitions. It is not only ethically appropriate but also necessary for Canada to capitalize on Russia’s blunders and strengthen its position as a responsible and reliable global energy superpower.

About the author

Dr. Sergey Sukhankin is a Senior Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation (Washington, DC) and a Fellow at the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN). Sukhankin has extensively researched issues relating to trade and business in the Arctic region. He has particularly focused on oil and natural gas projects in the Arctic, as well as Russia’s trade in raw materials and commodities.

References

Abishev, Ilya. 2024. “Drone strikes on Russian oil refineries – a new challenge to Moscow or a propaganda image?” BBC News, February 8, 2024. Available at https://www.bbc.com/russian/articles/c29knl8ge52o

Alifirova, Ye. 2024. “ES v 2023 g. zakupil u Rossii nefti I gaza pochti na 30 mlrd. evro” (The EU purchased almost 30 billion euros worth of oil and gas from Russia in 2023). Neftegaz.ru, February 16, 2024. Available at https://neftegaz. ru/news/Trading/818984-es-v-2023-g-zakupil-u-rossii-nefti-i-gaza-pochti-na30-mlrd-evro/

Babanova Mariya. 2023. “Truba zovet – neftegaz Rossii na poroge 2024 goda” (The pipe is calling – Russian oil and gas on the threshold of 2024). Finam, December 27, 2023. Available at https://www.finam.ru/publications/item/ truba-zovet-neftegaz-rossii-na-poroge-2024-goda-20231227-1840/

Braslavskiy, Dmitriy. 2024. “Grecheskiye suda pochti polnostyu perestali transportirovat rossiyskuyu neft, – Bloomberg” (Greek ships have almost completely stopped transporting Russian oil, – Bloomberg). RBK- Ukraina, February 5, 2024. Available at https://www.rbc.ua/ukr/news/gretski-sudnamayzhe-povnistyu-perestali-1707155720.html

Canadian Gas Association 2024. “Natural Gas Facts.” Accessed 2024. Available at https://www.cga.ca/natural-gas-statistics/natural-gas-facts/

Chang, Felix K. 2017. “Effectiveness of Economic Sanctions on Russia’s Economy.” Foreign Policy Research Institute, June 1, 2017. Available at https:// www.fpri.org/2017/06/effectiveness-economic-sanctions-russias-economy/

Chizhevskiy, A. 2024. “Gazprom ustanovil ocherednoy record sutochnykh postavok gaza v Kitay” (Gazprom sets another record for daily gas supplies to China). Neftegaz.Ru, January 13, 2024. Available at https://neftegaz.ru/ news/transport-and-storage/811714-gazprom-ustanovil-ocherednoy-rekordsutochnykh-postavok-gaza-v-kitay/

Data Pandas. 2024. “Oil Reserves by Country.” Accessed 2024. Available at https://www.datapandas.org/ranking/oil-reserves-by-country

Derhally, Massoud 2024. “Wider Mideast War Could Bring $120 Oil: Report.” Energy Intelligence, February 16, 2024. Available at https://www.energyintel. com/0000018d-b185-d797-a7ed-fdb55cf40000

Heussaff, Conall, Lionel Guetta-Jeanrenaud, Ben McWilliams, and Georg Zachman. 2024. “Russian crude oil tracker.” Bruegel, February 12, 2024. Available at https://www.bruegel.org/dataset/russian-crude-oil-tracker

Financial Times. 2023. “Almost no Russian oil is sold below $60 cap, say western officials.” November 13, 2023. Available at https://www.ft.com/ content/09e8ee14-a665-4644-8ec5-5972070463ad

Financial Times. 2024. “Gazprom grapples with collapse in sales to Europe.” February 18, 2024. Available at https://www.ft.com/content/ e1b65044-1a97-429a-b1e2-c337a343ec2a

Gavin, Gabriel. 2023. “Fight against ‘shadow fleet’ shipping Russian oil takes EU into uncharted waters.” Politico, May 22, 2023. https://www.politico.eu/ article/russia-shadow-fleet-eu-sanction-ukraine-war-oil/

Glavnoye in UA. 2024. “Nochyu SBU atakovali dronami tri neftepererabatyvayushchikh zavoda RF” (During the night SSU Drones Strike Three Russian Oil Refineries). Glavnoye in UA. March 13, 2024. Available at https://glavnoe.in.ua/ru/novosti/nochyu-sbu-atakovala-dronamy-tryneftepererabatyvayushhyh-zavoda-v-rf#google_vignette

Gilchrist, Karen. 2022. “Russian oil price cap requires global commitment, France says, will be difficult to implement.” CNBC, September 3, 2022. Available at https://www.cnbc.com/2022/09/03/france-says-imposing-aprice-cap-on-russian-oil-will-be-difficult.html Golos Ameriki. 2024. “Tenevoy flot Rossii” (Russian “Shadow Fleet”).

Golos Ameriki, February 12, 2024. Available at https://www.golosameriki. com/a/7484426.html The Insider. 2024. “Rossiya v 2023 godu zarabotala 1 mlrd euro na prodazhe nefteproduktov v ES cherez tretyi strany – Politico” (Russia earned 1 billion euros in 2023 from the sale of petroleum products to the EU through third countries – Politico).

The Insider. 2024. “Rossiya v 2023 godu zarabotala 1 mlrd euro na prodazhe nefteproduktov v ES cherez tretyi strany – Politico” (Russia earned 1 billion euros in 2023 from the sale of petroleum products to the EU through third countries – Politico). The Insider, February 23, 2024. Available at https://theins.ru/news/269419

Interfax. 2024. “Rossiya v 2023 godu stala krupneyshym eksporterom nefti v Kitay” (In 2023, Russia Emerges as China’s Top Oil Exporter). Interfax, January 20, 2024. Available at https://www.interfax.ru/russia/941154

Itskhoki, Oleg. 2023. “Razocharovaniye goda: sankcii. Rossiyskuyu ekonomiku razrushat ne oni, a voyna.” (Disappointment of the year: sanctions. It is not they who will destroy the Russian economy, but the war). Vazhnyye Istorii, December 20, 2023. Available at https://istories.media/opinions/2023/12/20/razocharovanie-goda-sanktsii-rossiiskuyu-ekonomiku-razrushat-ne-oni-a-voina/

Izvestiya. 2023. “Eksperty otcenili perspektivy gazovogo haba v Turcii” (Experts assessed the prospects for a gas hub in Turkey). May 18, 2023. Available at https://iz.ru/1514760/2023-05-18/eksperty-otcenili-perspektivy-gazovogo-khaba-v-turtcii

Johnson, Simon, Łukasz Rachel, and Catherine Wolfram. 2023. “The design and implementation of the price cap on Russian oil.” VoxEU, August 19, 2023. Available at https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/ design-and-implementation-price-cap-russian-oil

Khasanova, A. 2024. “Indiya vozobnovlyayet zakupki rossiyskoy nefti Sokol” (India resumes purchases of Russian Sokol oil). Neftegaz. Ru, February 17, 2024. Available at https://neftegaz.ru/news/ Trading/819165-indiya-vozobnovlyaet-zakupki-rossiyskoy-nefti-sokol/ Kossov, Igor. 2024. “Ukrainian drones hit one Russian oil refinery after another.” Kyiv Independent, March 19, 2024. Available at: https://kyivindependent.com/ ukraine-targets-russian-oil-refineries/

Lenta. 2024. “Путин заявил о возможности запустить «Северный поток» за одну неделю Путин: для запуска сохранившейся нитки «Северного потока» нужна неделя” (Putin announced the possibility of launching Nord Stream in one week). February 18, 2024. Available at https://lenta.ru/news/2024/02/18/putin-zayavil-o-vozmozhnosti-zapustit-severnyy-potok-za-odnu-nedelyu/

Meduza. 2024. “The Moscow Times: yevropeyskiye kompanii v obkhod sanktsiy postavili oborudovaniye dlya proekta “Novateka” na 580 millionov evro” (The Moscow Times: European companies, bypassing sanctions, supplied equipment for the Novatek project worth 580 million euros). March 12, 2024. Available at https://meduza.io/news/2024/03/12/the-moscow-times-i-arctidaevropeyskie-kompanii-v-obhod-sanktsiy-postavili-oborudovanie-dlya-proektanovateka-na-580-millionov-evro

Moscow Times. 2024a. “Rossiya poteryala million tonneksporta nefteproduktov posle udarov Ukrainy po krupneyshym NPZ” (Russia lost a million tons of oil product exports after Ukraine struck its largest refineries). February 15, 2024. Available at https://www.moscowtimes.eu/2024/02/15/rossiya-poteryalamillion-tonn-eksporta-nefteproduktov-posle-udarov-ukraini-pokrupneishimnpz-a121724

Moscow Times. 2024b. “Европа и Китай договорились закупать больше газа в Катаре вместо российского” (Europe and China agreed to buy more gas from Qatar instead of Russia). February 21, 2024. Available at https://www.moscowtimes.ru/2024/02/21/evropa-ikitai-dogovorilis-zakupat-bolshe-gazavkatare-vmesto-rossiiskogo-a122386

Neft kapital. 2023. “Tenevoy flot rastet, kolichestvo operatciy bort-v-bort uvelichivaetsya” (The “shadow fleet” is growing, the number of board-to-board operations is increasing). March 7, 2023. Available at https://oilcapital.ru/news/2023-03-07/tenevoy-flot-rastet-kolichestvo-operatsiy-bort-v-bort-uvelichivaetsya-2812540

Nefte Gaz 2024a. “Индия в 2023 г. нарастила импорт нефти на 4,5%.” (India increased oil imports by 4.5% in 2023). February 19, 2024. Available at https://neftegaz.ru/news/Trading/819512-indiya-v-2023-gnarastila-import-nefti-na-4-5/

Nefte Gaz 2024b. “Индия возобновляет закупки российской нефти Sokol.” (India resumes purchases of Russian Sokol oil). February 17, 2024. Available at https://neftegaz.ru/news/ Trading/819165-indiya-vozobnovlyaet-zakupki-rossiyskoy-nefti-sokol/

Nesheiwat, Julia. 2024. “Escalating Middle East conflict means North America must bolster global energy security.” Atlantic Council, February 24, 2024. Available at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/energysource/ the-escalating-conflict-in-the-middle-east-and-its-impact-on-global-energysecurity/

Novak, Aleksandr. 2024. “Dobycha v RF nefti s kondensatom v 2023 godu upala menee chem na 1%” (Oil with Condensate Production in Russia Declined by Less Than 1% in 2023). Interfax, January 25, 2024. Available at https://www. interfax.ru/business/941855

Novatek 2024. “Project Arctic LNG 2.” Accessed 2024. Available at https://www.novatek.ru/en/business/arctic-lng/

Pao, Jeff. 2024. “Power of Siberia 2 stuck on gas price, branch issues.” Asia Times, January 20, 2024. Available at https://asiatimes.com/2024/01/power-of-siberia-2-stuck-on-gas-price-branch-issues/

Parshynova, P. 2023. “Inostrannyye akcionery proekta Arktik SPG-@ obyavili fors-mazhor po uchastiyu v proekte” (Foreign shareholders of the Arctic LNG2 project declared force majeure on participation in the project). Neftegaz.ru, December 25, 2023. Available at https://neftegaz.ru/news/spg-szhizhennyyprirodnyy-gaz/808905-inostrannye-aktsionery-proekta-arktik-spg-2-obyavilifors-mazhor-po-uchastiyu-v-proekte/

Parshynova, P. 2024. “Uganda vedet peregovory s Rossiyey o stroitelstve NPZ” (Uganda Engages in Discussions with Russia for Refinery Construction). Neftegaz.Ru, February 19, 2024. Available at https://neftegaz.ru/news/ neftechim/819497-uganda-vedet-peregovory-s-rossiey-o-stroitelstve-npz/

Pipeline Journal 2023. “Power of Siberia 2: Like the Bridge to Nowhere?” November 11, 2023. Available at https://www.pipeline-journal.net/ news/power-siberia-2-bridge-nowhere#:~:text=The%20Power%20of%20 Siberia%202,and%20Russia%20will%20lose%20money.

Ratcliffe, Verity and Walid Ahmed 2024. “Qatar to Announce More LNG Deals with European, Asian Buyers.” Bloomberg, February 19, 2024. Available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-02-19/qatar-will-announce-more-lng-deals-with-european-and-asian-firms

RBK. 2024. “Pravitelstvo na polgoda zapretit eksport benzina” (The government will ban gasoline exports for six months). RBK, February 27, 2024. Available at https://www.rbc.ru/business/27/02/2024/65dcc83c9a79471518ed08bd

Ria Novosti. 2022. “SMI: Polsha predlozhyla snizit potolok tcen nan eft iz Rossii v dva raza” (Media: Poland proposed to halve the price ceiling for oil from Russia). Ria Novosti, November 24, 2022. Available at https://ria. ru/20221124/potolok-1833845751.html

Rosstat. 2022. “O rynke nefti v 2021 godu” (The oil market in 2021). March 14, 2024. Available at https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/27_23-02-2022.html

Sankranti, Shashwat. 2023. “Decoding Russia’s $11 bn end run around Western oil sanctions.” WION, December 8, 2023. Available at https://www.wionews. com/business-economy/russias-11-bn-end-run-around-western-oil-sanctionsshadow-fleet-and-deals-unearthed-667518

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2024a. “Russia’s Arctic-Based Oil Mega-Project Struggles to Attract Foreign Investors.” The Jamestown Foundation, January 24, 2024. Available at https://jamestown.org/program/ russias-arctic-based-oil-mega-project-struggles-to-attract-foreign-investors/

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2024b. “US Sanctions Hamper Russia’s LNG Strategy in the Arctic.” The Jamestown Foundation, January 9, 2024. Available at https://jamestown.org/program/ us-sanctions-hamper-russias-lng-strategy-in-the-arctic/

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2024c. “Biden’s LNG Decision Sparks Hope for Russia’s Energy Industry.” The Jamestown Foundation, February 1, 2025. Available at https://jamestown.org/program/ bidens-lng-decision-sparks-hope-for-russias-energy-industry/

Sukhankin, Sergey. 2021. “Russian LNG Shipments to India: Strategic Implications and Long-Term Prospects.” The Jamestown Foundation, November 2, 2021. Available at https://jamestown.org/program/russian-lngshipments-to-india-strategic-implications-and-long-term-prospects/

Sonnenfeld, Jeffrey A., and Steven Tlan. 2022. “How the Russian Oil Price Cap Will Work.” Foreign Policy, September 6, 2022. Available at https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/06/ russia-oil-price-cap-putin-war-sanctions-energy-g7-europe-crisis/

Tanker Trackers (@TankerTrackers). “So, a tanker that had violated the G7 price cap of $60/barrel on Russian oil last year by using Western insurance, is now insured once again through a different Western institution while receiving oil via an STS transfer inside Iran. #OOTT Fa-la-la-la-laaaa-la-la-la-laaaa!” February 22, 2024. [X post]. Available at https://twitter.com/TankerTrackers/ status/1760775248918540728?s=20 TASS. 2024. “Western sanctions will not bring Russia to its knees, says Finnish banker.” March 13, 2024. Available at https://tass.com/economy/1758843

Vedomosti 2023. “Роснефть» представила проект ‘Восток ойл’ на выставке ‘Россия’” (Rosneft presented the Vostok Oil project at the Russia exhibition). November 7, 2023. Available at https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/ articles/2023/11/07/1004470-rosneft-predstavila-proekt-vostok-oil-navistavke-rossiya

Wong, Kandy. 2023. “China wielding ‘bargaining power’ with Russia over Power of Siberia 2 natural gas pipeline.” South China Morning Post, November 24, 2023. Available at https://www.scmp.com/economy/global-economy/ article/3242612/china-wielding-bargaining-power-russia-over-power-siberia2-natural-gas-pipeline

YouTube 2023. “Interview with the President of Transneft PJSC N.P. Tokarev TV channel ‘Russia 24.’” Transneft, December 20, 2023. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtGjfa5UATQ