By Stephen Van Dine and Karl Salgo, March 17, 2023

Occasionally, the Oath of Allegiance to the sovereign enters the news cycle. Most often, it is raised in the popular debate of whether Canada’s constitutional ties to the monarch as a head of state are anachronistic. For some office holders it’s cast as a kind of “conscientious objection” to the concept of a monarchy. But these views are grounded in confusion.

What’s in an oath?

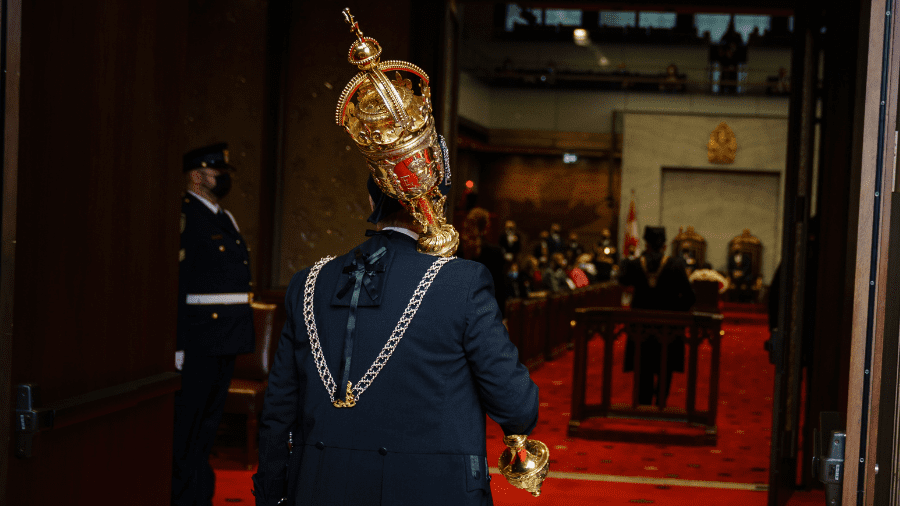

Privy Councilors, Supreme Court Justices, the Canadian Armed Forces, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, among others, all take an oath of allegiance to the King or sovereign, the person who embodies the Crown. But when an officeholder swears allegiance to the monarch, they aren’t committing to a personal, or even a political, belief in the principle of hereditary office. Taking the oath is an acceptance of the legitimacy of our constitutional system – one in which the Crown heads each branch of government: legislative, executive, and judicial.

Like it or not, the monarch is the legal repository of all authority of the Canadian state (although most of his powers are exercised by the Governor General). A minister is a minister of the Crown and exercises power only in its name. In formal terms, prime ministers and their cabinets are merely advisors to the Crown, such that decisions of Cabinet acquire the force of law only as acts of the Governor in Council. If nothing else, this puts prime ministers in their place.

Does an oath matter in practice?

It’s easy to think of the oath of allegiance as something purely symbolic and as such dispensable. Our prime minister sometimes appears to think so. But oath takers put their integrity on the line, and a blithe attitude towards such “symbols” contributes to the toxic cocktail of declining trust in our public institutions and legitimacy.

Recent revelations of China’s interference into Canada’s last two federal elections as well as related intelligence leaks by unnamed intelligence sources to the Globe and Mail and Global News have shown how vulnerable our institutions can be, including the public service tradition of speaking truth to power.

One of the extraordinary things about the system to which a Canadian officeholder swears allegiance is the deep well of conventional, which is to say mostly unspoken, rights and obligations that it taps into.

To take one example of these deep historical roots, when William Cecil, principal counsellor to Elizabeth I for 40 years, entered her service she required three commitments from him:

that you will not be corrupted with any manner of gift, that you will be faithful to the state, and that without respect of my private will, you will give me that counsel that you think best.

In less than one sentence Elizabeth required a commitment to honesty and avoidance of conflict of interest, to acting in the public interest, and to speaking truth to power. Much of the content of our public service code and conflict of interest act is a less pithy and eloquent codification of these three centuries-old principles.

Incidentally, Elizabeth committed herself to a reciprocal confidentiality, such that what Cecil confided in her he should “assure yourself I shall keep taciturnly therein.”

Truth to power: A reciprocal commitment

Elizabeth’s commitment to her counsellor reminds us that oaths by office holders can carry reciprocal, if unspoken, commitments on the part of the Crown. Being obliged to speak truth to power, for instance, implies a commitment by the Crown not to mete out punishment for truths it doesn’t want to hear.

Unlike whistleblowing protections that afford those who risk personal career harm or injury by bringing to light unlawful behaviour for fraud by governments, the oath requires its keeper to give fearless advice even when the receiver is likely not asking for it.

In the case of alleged leaks of intelligence information to the media by unnamed officials, there is much we do not know. We do know that the RCMP is investigating and will determine if the Secrecy Act has been breached. We also may never know the granularity of the information provided to the prime minister and officials in his office. We can assume, however, that the office holders providing the intelligence briefings were obligated to provide “fearless advice” on the nature of the threat and likely means to mitigate such threats.

A key question is, was the information leaked to media materially the same or different from the material used to brief the prime minister and his office? How thorough was the advice? Did the Prime Minister’s Office acknowledge receipt and take a different course than was recommended (which is their democratically elected prerogative). Alternatively, was the information and advice provided limited or perhaps even diluted?

If the latter, then “fearless advice” is being undermined. The intelligence sources who leaked the information may be prime candidates to test the level of reciprocity that comes with an oath of allegiance: To serve faithfully, honestly and fearlessly and to be shielded (protected) from potential political or career reprisal.

Acknowledging the authority, you seek to exercise

Many people think the Westminster system, including the concept of the Crown, is one of humanity’s greater achievements. Readers are under no obligation to agree. But if you want to participate in the exercise of the Crown’s authority – even for the purposes of seeking its abolition – you must acknowledge it. Legally speaking, when and if the monarchy is ever abolished in Canada, it will be by and with the assent of the monarch.

When we dismiss oaths, we blithely toss away the richness and gravitas of the Canadian state, for the sake of a glib confusion.

Stephen Van Dine is the former Assistant Deputy Minister of Northern Affairs for Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Karl Salgo is Executive Director of Public Governance at the Institute on Governance.