By Heather Exner-Pirot

April 14, 2025

It is inconceivable that all lands north of the 60th parallel, representing 35 per cent of Canada’s total land area, which we believe contain a great natural resource potential, will remain as an undeveloped portion of Canada. The resources are there, although the people and private industry are as yet not there in sufficient numbers.

— Hon. Arthur Laing, Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources, 1966

In the rush to diversify Canada’s trade routes and export destinations, provincial, territorial, and federal politicians of all partisan stripes have heralded new corridors and ports. With major ports already established on the Pacific side, in Vancouver and Prince Rupert; and the Atlantic side, in Montreal, Halifax, and Saint John; attention has turned to the Arctic.

The region has become, again, of interest for its shipping routes, resource development, and security importance. The politics of northern development are attractive, but are the economics? Is there a rationale for Canada to develop northern corridors to ports on our Arctic coasts?

Unfortunately, the answer is, not much. Roads and seasonal ports in the Canadian North are incredibly expensive to build and maintain, and their use case is limited. There are legitimate reasons to develop Arctic corridors to tidewater, but they are driven by social and political objectives, not economic ones. Eastern, and especially western, options are what will drive Canadian economic growth and diversify its trade.

Go north, young man

Canada, famously, has the longest coastline of any country in the world. It has great access to tidewater on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts, allowing it to reach lucrative Asian and European markets. But it has focused most of its trade efforts at developing routes to the enormous American market to the south. Until November 2024 this proved beneficial, but with the turmoil and tariffs of the Trump Administration, Canada’s dependence now poses great risks.

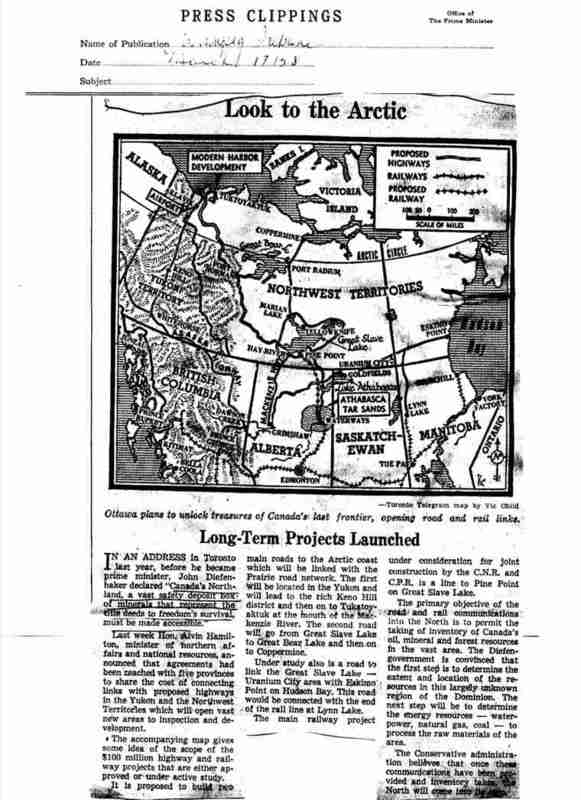

For over a hundred years there have been calls for Canada to develop corridors to the North to diversify trade routes. Depending on the stage of the commodity cycle, these calls grow louder or quieter. Today, they are loud.

Figure 1: Newspaper clipping from 1953 on proposed northern corridors

The only successful one, the Port of Churchill, sitting on Hudson Bay in Northern Manitoba, was first proposed in 1880. A nearby competitor, Port Nelson, actually saw construction in the 1910s, but it was abandoned in 1918, due to the location’s shallow waters and exposure to northern winds. Attention returned and stayed with Churchill thereafter. The Hudson Bay Railroad reached the Port of Churchill in 1929 and began exporting grain in 1931 seasonally between July-October, when the port and shipping route is ice free.

The feasibility and profitability of the port waxed, but mostly waned, for the next 65 years. In 1997, Canadian National Railway privatized and sold the port to OmniTRAX, a US firm, for a nominal $10, as well as the railroad for $11 million. It saw reasonable grain exports in the 2000s, as the Canadian Wheat Board, a monopsony, directed wheat exports through Churchill. After the Marketing Freedom for Grain Farmers Act was passed in 2011, farmers and grain companies were free to choose West Coast ports and American routes instead, which were preferred due to their year-round access, bigger terminals, and proximity to Asian markets. Churchill’s seasonal operation and smaller capacity made it uncompetitive. OmniTrax suspended grain shipments in 2016.

A flood in 2017 that wiped out much of the track further exacerbated Churchill’s challenges. There were no grain deliveries to interrupt, but the communities along the route and in Churchill itself lost land service (there is no highway north of Sundance, near Gillam, Manitoba), and were forced to rely on more expensive air and sea supply.

An Indigenous and private investor consortium, the Arctic Gateway Group, bought the railroad and port with federal support of $117 million, and returned it to service 18 months later. The private investors, AGT Foods and Fairfax Holdings, were initially optimistic about the route’s potential. However they sold their 50 per cent share back to the Indigenous partners in 2021, minimizing exposure to what was a low-return asset, and AGT foods has not delivered product on the line since then.

The port has struggled to attract much business, and is operating well below capacity. According to publicly available sources, no grain has been shipped since 2020, although a single critical minerals cargo – 10,000 tonnes of zinc concentrate from HudBay Minerals – was shipped from Churchill to Europe in August 2024, the first mineral shipment in over two decades. At least one cruise ship docked in 2023, and the port has been used for a handful of community resupply shipments each year as well.

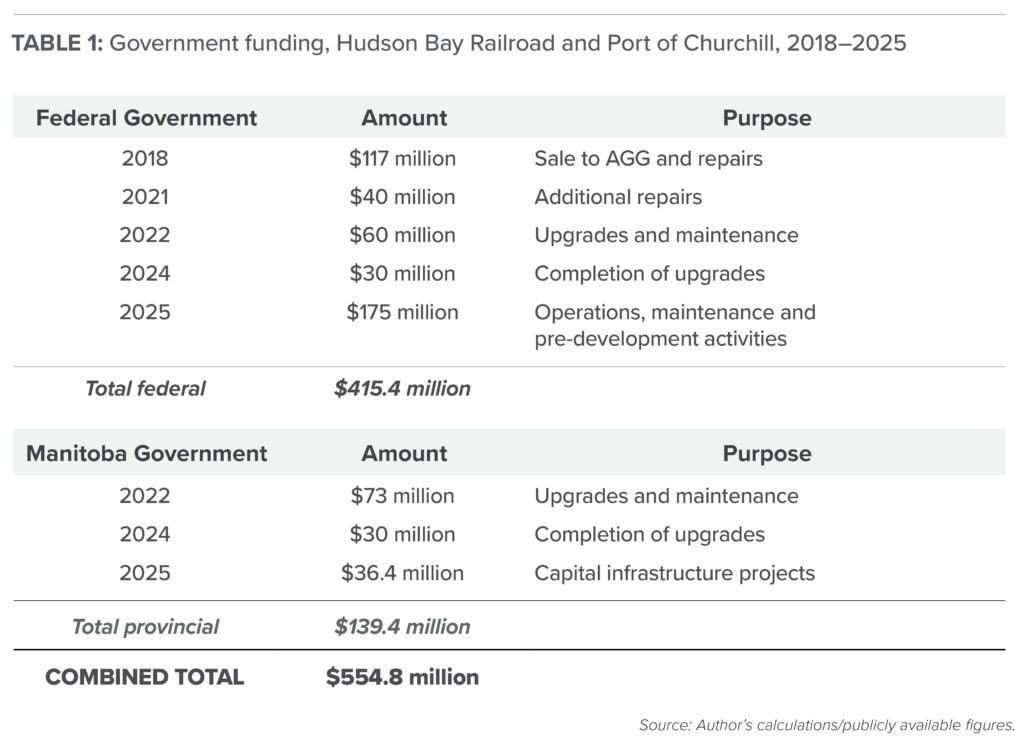

The use of the Port of Churchill is not commensurate with the government funding provided to sustain its operations (Table 1). Port operators are optimistic about future prospects and actively seeking new shippers, and the railroad and port are important for the few remote communities it serves. But there is no reason to think it will become a significant export option for Canadian grains, critical minerals, oil, or natural gas in the medium term.

There have recently been renewed attempts to build up Port Nelson, through the Indigenous-led NeeStaNan Utility Corridor Project , but it has not advanced very far.

There have recently been renewed attempts to build up Port Nelson, through the Indigenous-led NeeStaNan Utility Corridor Project , but it has not advanced very far.

Canada’s Arctic Ports

In addition to Churchill, Canada has a number of other ports in Arctic waters, although none are connected to major highway or rail networks. All of them are seasonal, i.e. they are ice free for only a few months a year. They include Iqaluit’s deep sea port, which opened in 2023; and ports for mining operations including Mary River iron mine’s port at Milne Inlet on Baffin Island, Nunavut; the Raglan nickel mine port at Deception Bay in northern Quebec; and the Voisey’s Bay nickel mine port at Anaktalak Bay in Labrador. Voisey’s Bay does some shipments in the winter with the help of the ice strengthened carrier MV Umiak I.

In addition, a naval refuelling facility is being developed in Nanisivik, Nunavut, though it is several years overdue. It was previously the location of a lead-zinc mine which closed in 2002. Although Arctic sovereignty is often referenced as rationale for Arctic ports, Canada’s current coast guard and naval icebreakers are designed with very long ranges (the CCGS Louis St. Laurent has a range of 43,000 km and the Arctic Offshore Patrol Ships of 12,600 km; the CCGS Arpaatuq will have a range of 48,500 km). Nanisivik will be useful but its delay has not interrupted operations; an additional port or refuelling facility a few hundred kilometers away would not meaningfully enhance capabilities.

Other locations mentioned as potential sites for Arctic ports are Tuktoyaktuk (NWT), and Gray’s Bay (Nunavut), which sit along the Northwest Passage, and Qikiqtarjuaq (Nunavut), which sits on Baffin Bay a few hundred kilometres north of Iqaluit.

Tuktoyaktuk was connected by road to Inuvik and the NWT highway system in 2017, partly under the premise of facilitating natural gas development in the region. However, it sits near the mouth of the Mackenzie River Delta and its shallow waters make it unsuitable as a deep water port capable of exports.

Qikiqtarjuaq is proposing a deep water port, but its purpose would be to support local fisheries and allow for more tourism and trade. As it is on Baffin Island, it would not have any linear infrastructure to other communities.

The only true candidate for a northern corridor terminus is a port at Gray’s Bay, in Nunavut’s Kitikmeot region. It would serve as Canada’s first deepwater port on the western Arctic coast, and in combination with the proposed road, link it to a highway system to Canada.

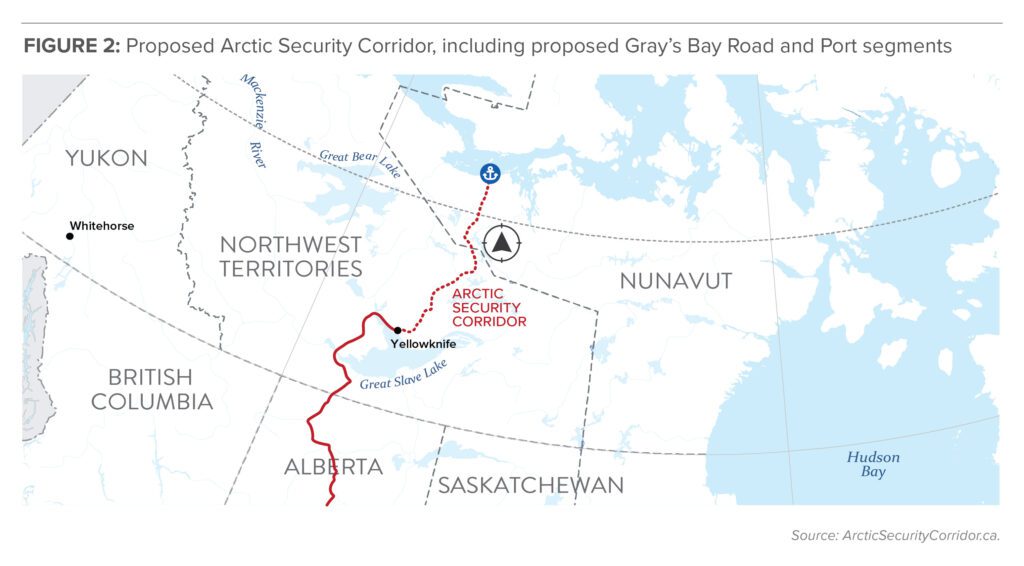

The proposed Gray’s Bay Road and Port project is closely connected with the Slave Geological Province Corridor, and is an effort to bring linear infrastructure into the resource-rich region to facilitate mine development. The full corridor has been referred to by Northwest Territories Premier R.J. Simpson, Nunavut Premier P.J. Akeeagok, and Alberta Premier Danielle Smith as an “Arctic Security Corridor” from Alberta to the Arctic Ocean (see Figure 2). The project entails a 413 km all-season road (the dotted red line on the Figure 2 map) from Yellowknife the NWT-Nunavut border; connecting to a 230 km road in Nunavut to Gray’s Bay (indicated by the anchor symbol) and the Northwest Passage. West Kitikmeot Resources Corp submitted an application for the Nunavut side of the project to the Nunavut Impact Review Board in February 2025.

The Slave Geological Province is a promising jurisdiction for mining, although much remains to be explored. It hosts three active diamond mines (Ekati, Diavik, Gahcho Kué) that together comprise about a quarter of NWT’s GDP. There are currently no other operating mines in the NWT, and all three diamond mines are nearing the end of their lifespan, with Diavik set to end commercial operations first, in early 2026. This poses a tremendous economic challenge to the territory, which the Arctic Security Corridor promises to help address.

The most likely candidates for new mines in the Slave region are the Izok Lake and High Lake deposits, referred to as the Izok Corridor Project. Izok has a resource of 15 million tonnes at 13 per cent zinc and 2.3 per cent copper, with minor lead/silver deposits. High Lake has a resource of 14 million tonnes at 3.8 per cent zinc and 2.3 per cent copper. While Izok and High Lake were discovered in the 1970s and 1950s respectively, the economics have never pushed them to development phase due to the lack of infrastructure and remoteness of the region. Government support is required to develop the infrastructure to make the project’s economics work.

A further complication is that the deposits are owned by MMG Limited, a subsidiary of China MinMetals. One would expect it would need to be sold to a western developer before any Canadian taxpayer money could be devoted to further assisting it.

The less accessible Arctic

A significant driver for calls to develop northern corridors is the assumption that climate change is opening up Arctic shipping routes and resources, and Canada needs to act to take advantage of this opportunity, lest our adversaries do so first. As Canada’s Defence Policy Update from May 2024, titled Our North, Strong and Free, described it:

“By 2050, the Arctic Ocean could become the most efficient shipping route between Europe and East Asia. Canada’s Northwest Passage and the broader Arctic region are already more accessible, and competitors are not waiting to take advantage – seeking access, transportation routes, natural resources, critical minerals, and energy sources through more frequent and regular presence and activity.”

In fact, climate change is making shipping and resource development in the Arctic harder, not easier. This is owing to three factors: difficult sea ice, and thus shipping, conditions; melting permafrost; and a shorter ice road season.

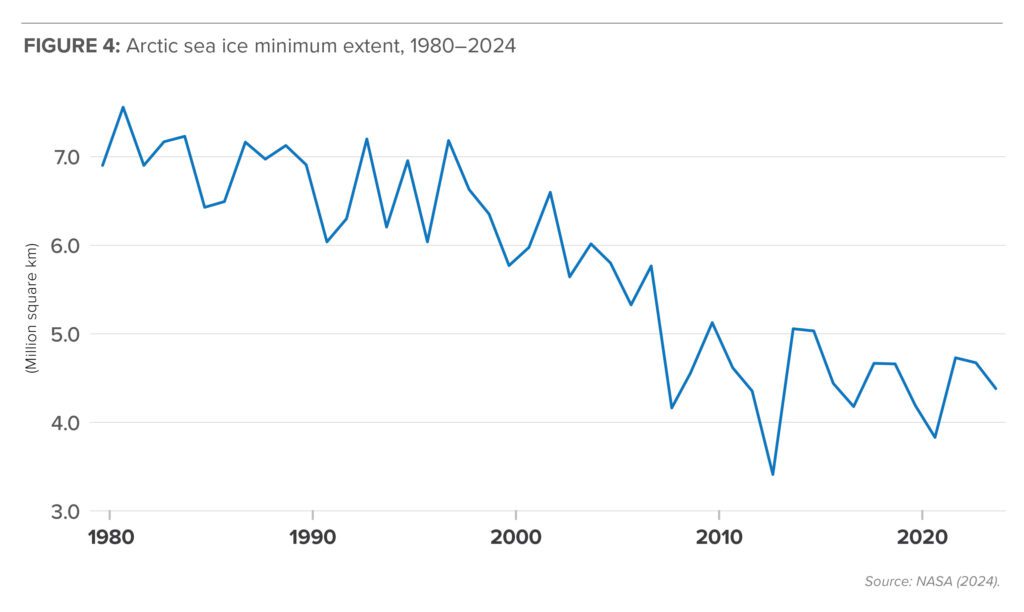

Arctic sea ice has indeed declined substantially. Around September 15 every year, the minimum annual extent is reached, and as Figure 3 indicates, it has shrunk significantly from the 1981–2010 median edge: from an average of about 7 million km2 to about 4.5 million km2. The years 2007 and 2012 were particularly bad, with dramatic declines that led to predictions that the Arctic would soon be “ice free.” Environmentalist and former Vice President Al Gore, for example, suggested in 2009 that the ice could be gone within five years.

But rates of sea ice melt have declined significantly since hitting its record low in 2012, and since 2012–24 has been minimal (Figure 4). This is not because climate change has stopped, but rather because the dynamics that led to the dramatic melt from 2000–2012 have changed. In those years, the Arctic’s thick and old ice was lost. What’s left now is largely seasonal – 70 per cent of it – but it returns every year following the dark and cold Arctic winters. The ice has absolutely changed; but it’s also melting at a much slower rate.

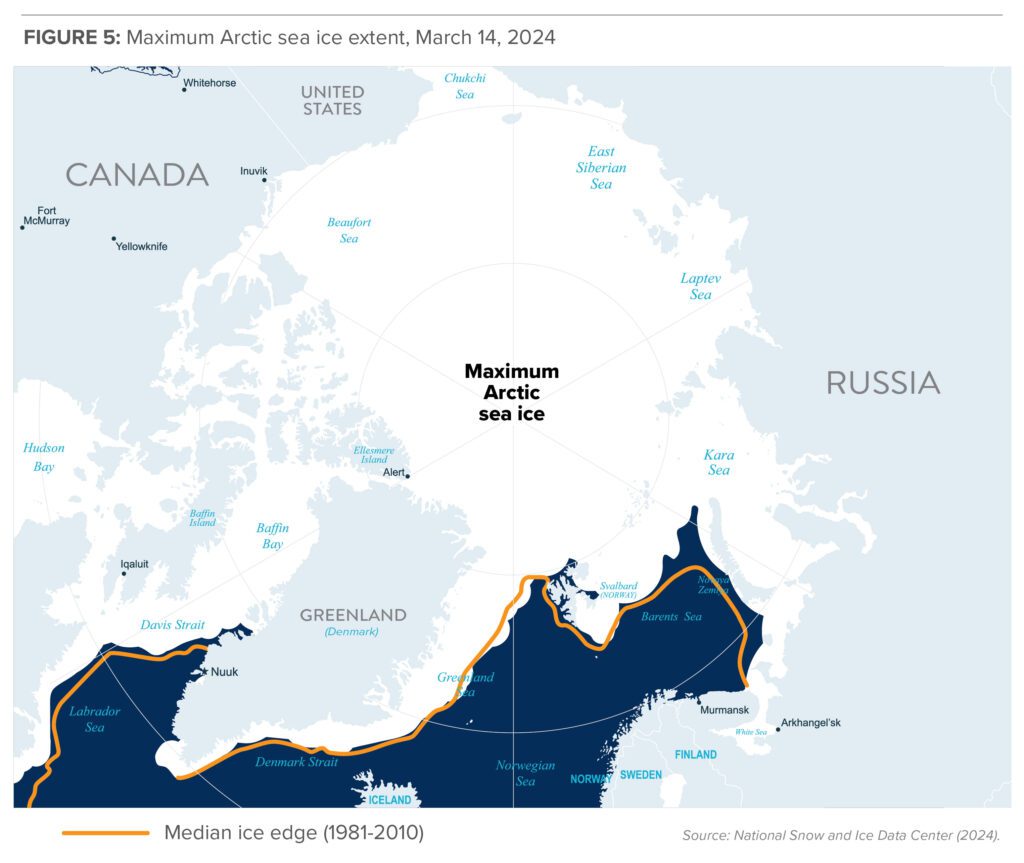

While headlines and speeches tend to focus on the September minimum sea ice extent, around March 15 every year, we see its maximum (Figure 5). And it is much more stable, such that it extends around 95 per cent of the 1981–2010 median edge.

This is not a commentary on rate of sea ice melt, but of Arctic corridor development. It’s clear that the conditions for Arctic shipping (and thus resource extraction) are not much improving.

In the best case scenario, what was once a three or four month shipping season may now be a five month shipping season. But for the most part, even that is not true. As peer-reviewed research published in Nature in 2024 has shown, the changing sea conditions and decline of older, thicker ice are actually making the Northwest Passage more difficult to cross. The shipping season has actually gotten shorter in the Canadian Arctic as multi-year ice is flushed southwards and creates chokepoints along certain route sections.

The NWP is a much less attractive route than Russia’s Northern Sea Route (NSR), as it is icier, narrower, and shallower. But the NSR is not getting easier to navigate due to climate change either. The head of the NSR Administration stated in March 2025 that they have also witnessed a worsening of the ice situation and more complicated conditions, and they do not anticipate shipping through the region will get any easier over the next two decades.

The Canadian Arctic, of course, is a huge region and shipping access is far from the only, or even the most, important factor in whether a project is economic or not. Base metal and iron mines, which depend on large volumes, have tended to be developed only where deposits are very close to tidewater (e.g. current Mary River, Raglan, and Voisey’s Bay mines, and previous Nanisvik and Polaris mines) and where ore can be easily shipped. Much of what has been developed in the interior is diamonds and gold, which have very high value to weight ratios, and are able to be transported via air.

In general, interior mines have depended on winter road access for resupply, including the storage and shipping of tens of million of litres of diesel to sustain year long operations. But climate change has been making ice road seasons shorter, compressing timelines and challenging logistics. For example, the ice road season for NWT’s diamond mines is usually about two months; in 2024, it was delayed by two weeks. The problem is even more acute in the provincial north.

Finally, permafrost thaw is posing challenges to linear infrastructure in the Canadian north, including the Hudson’s Bay Railway to Churchill, the Mackenzie Northern Railway to Hay River, and the Inuvik-Tuktoyaktuk and the Dempster Highways. This was assessed to be a factor in the Hudson’s Bay Railway flood and washout in 2017. Plans to build new roads, railroads or pipelines as part of a northern corridor will have to contend with the challenging conditions and raised costs that building on melting permafrost will continue to create.

Seasonal ports: Less use, more cost

The main reason northern corridors to Arctic tidewater have not been developed at any scale in Canada is because a seasonal port is a far worse investment than a year-round port. It will never be possible for a Churchill or Gray’s Bay to compete with Vancouver or Montreal, or even Prince Rupert and Saint John for investment and shipments; the business case will never be as good.

It is often suggested that a lack of a northern corridor is a particularly Canadian affliction, and a result of our lack of ambition. But it is worth noting that seasonal ports are equally challenged in other Arctic countries. What makes Canada unique is that all of our Arctic ports are seasonal; the entire region is covered in ice in the winter. Where greater Arctic resource development has occurred, it has been bolstered by better port accessibility. Anchorage in Alaska, Nuuk in Greenland, Reykjavik in Iceland, Murmansk in Russia and all of Norway are year-round ports, owing to warmer currents. They are not nearly as ice constrained as the Canadian Arctic and that has made a huge difference in their ability to develop.

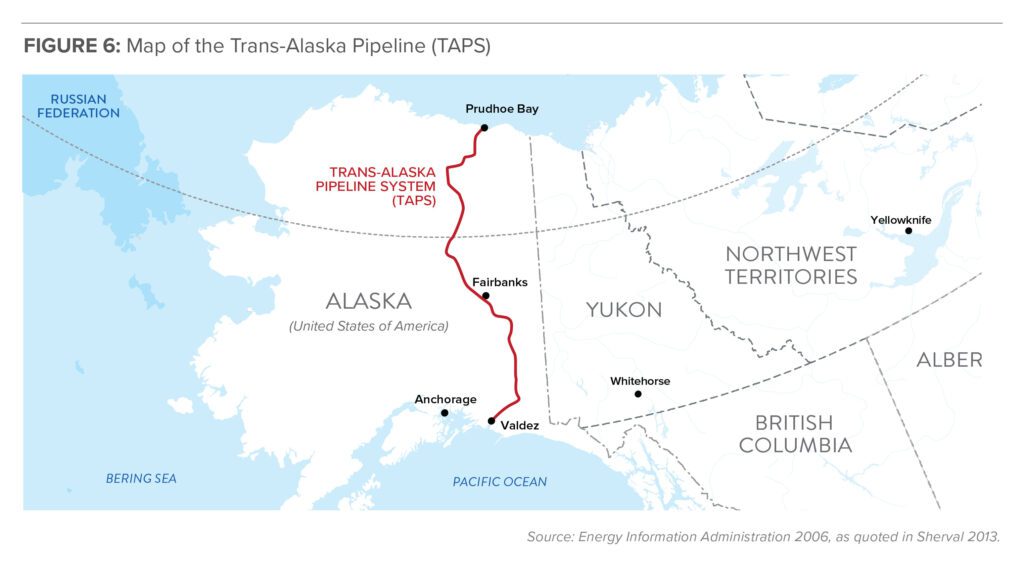

The clearest demonstration of the uncompetitiveness of seasonal ports is Alaska’s oil export infrastructure. Alaska’s oil and gas production is actually concentrated on its North Slope. But rather than suffer under the expense and burden of shipping through the seasonally ice-covered Prudhoe Bay, they built the 1288 km Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) in 1977, from northern Alaska to the port of Valdez on its southern coast, where oil can ship year round (Figure 6). The proposed Alaska LNG project would likewise build a pipeline from the north coast to a southern port.

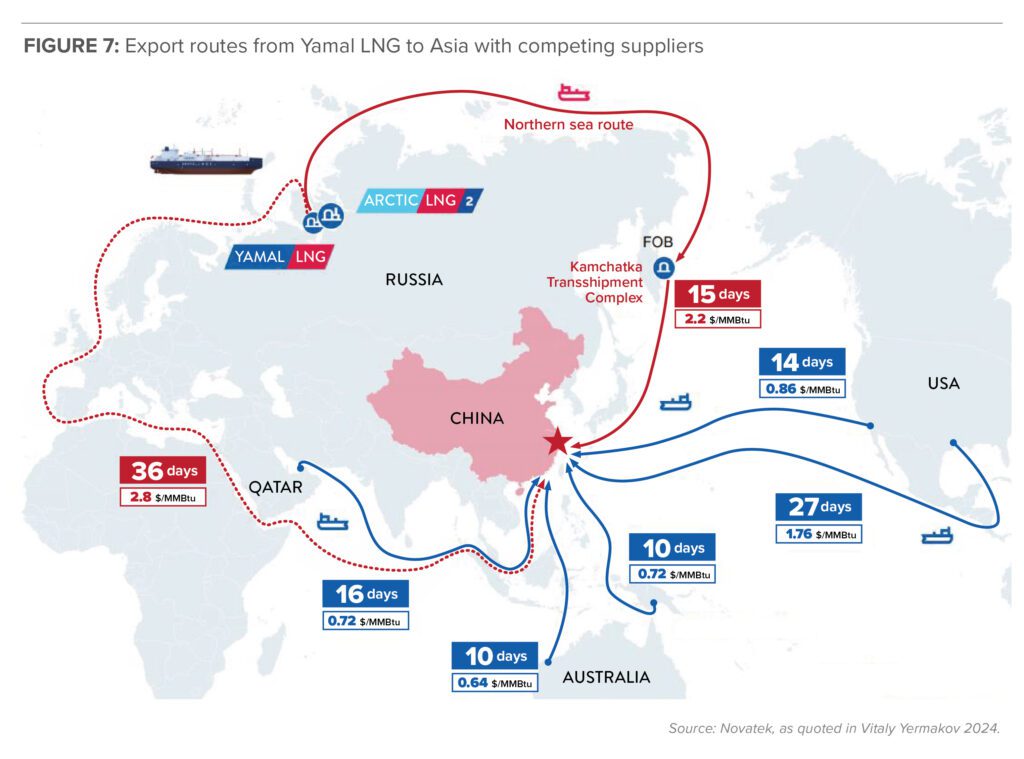

Russia is the obvious outlier in Arctic port infrastructure. Russia is an enormous producer and exporter of oil and gas, and the majority of its resources are located in its Arctic region: about 80 per cent of its natural gas and 60 per cent of its oil. While resource development across the Arctic slowed since the global commodities cycle downturn in 2015, Russian LNG has proved an exception. This is owing to two factors: one is the recent acceleration in global LNG trade, partly sparked by the availability of cheap shale gas post-2008; the other is the existence of the tremendous natural gas resource in and around the Yamal Peninsula.

Because Yamal LNG is located along the Northern Sea Route, it requires ice-capable LNG carrier vessels. South Korea’s Daewoo shipbuilding company built 15 “Yamalmax” Arc7 carriers for Yamal LNG. They each have a capacity of 170,000 cubic metres of natural gas, and measure 299 metres in length and 50 metres in width. They are powered by 45 MW engines which can be fuelled by either marine fuel oil, diesel, or LNG, and can travel at a speed of 19.5 knots in open water and at a reduced speed of 5.5 knots through sea ice up to two metres thick. They use an Azipod propulsion system that allows them to move both forward and astern through ice.

This system is expensive and complicated. Yamal LNG depends on being able to ship product westwards to Europe in the winter, when the NSR is unnavigable and shipments cannot go east to Asia. Indeed, the majority of Yamal’s shipments were always intended to be for European, rather than Asian, markets. However, the sanctions imposed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 have jeopardized Russian Arctic LNG export plans. Russian LNG giant Novatek had to issue a force majeure in February 2025 to warn it would not be able to honour contractual obligations in relation to Arctic LNG 2.

The case of Alaska and Russia patently do not inspire confidence in the prospects for oil or gas shipments out of seasonal Canadian Arctic ports. To summarize, Alaska sends its oil (and will send its gas) to southern, ice free ports via long pipelines rather than contend with an ice-covered port in Prudhoe Bay. Russia, which has no such luxury, has secured an expensive ice-strengthened LNG carrier fleet, but still must ship its product west to warmer European waters, rather than east through the ice covered NSR, in the winter months. Russia’s resource is in the Arctic; it is inconceivable that they would build linear infrastructure to go to the Arctic coast if the deposit was closer to open water elsewhere.

West Coast, best coast

One driver for building northern corridors is to provide alternate routes for Alberta’s enormous but land-locked oil and natural gas reserves. While eastern and western ports would obviously be superior in terms of greater cost competitiveness and lower environmental risk, governments in Victoria, Ottawa, and Quebec City have been obstructive, and building sufficient egress has been a perennial problem. An expensive export corridor through the Prairies or the territories is seen as better than no export corridor to BC or Atlantic Canada.

While this is true, it is unacceptable. The shortest, most obvious, cost effective, and least environmentally risky corridor for pipelines for Western Canadian oil and natural gas is to BC’s West Coast: Vancouver, Prince Rupert, Kitimat, or environs. This route leads to the world’s biggest and fastest growing energy market: Asia. It is not okay for Canadian energy to be blocked from access to Pacific tidewater, such that they must now entertain far less competitive and logical options going north. The Canadian federal government has the authority and the responsibility to make sure such projects get built, and must exercise it.

The Case for northern corridors

Canada has a tremendous natural resource endowment. It is excellent at mining, producing oil and gas, and growing crops. Its economy would thrive if it did more of that, and sent more of its products to trading partners beyond the United States. Allies in Asia and Europe would also be more secure if they could have better access to energy, minerals and food, of which they are net importers, from a reliable and democratic trade partner.

The priority in efforts to expand Canadian trade should be to address the inefficiency and disruption often experienced at our existing ports and railroads, and to build more pipelines to the West Coast.

Developing northern corridors would rank well below that, since the cost of building and maintaining railroads, roads and ports to Arctic tidewater are very high and the volume they would export would always be small. Canada has adopted a “build it and they will come” approaches before – the Hudson Bay Railroad, the Inuvik-Tuktoyaktuk Highway, the Dempster Highway – but they have not come.

There is a case for northern corridors, but it is not to increase exports. It is to support the centuries-long effort at building the nation of Canada. This means ensuring more of its northern and remote communities have good economic prospects, as well as reasonable access to transportation networks that enable them to travel and obtain supplies at a level comparable to their fellow citizens in the south.

Canadian oil and gas are very unlikely to be shipped and exported through northern ports. Corridors that allow Northern Canada to develop more of its mineral deposits and export them, even seasonally, through northern ports, will not create a ton of national wealth but can have a large impact at the regional level: the Pine Point Railway in NWT is one example of a railway built with government support but which provided a healthy return on investment. The trade-offs between the large investments needed to build and maintain such linear infrastructure, and the investment that could be directed to competing economic and social needs of northerners, must be carefully examined.

Canada needs to be extremely smart and strategic with the investments it makes in our Arctic. There is enough real demand for infrastructure in the Canadian Arctic to not be distracted by quixotic schemes. Our political leaders must get better at determining which are the former and which are the latter.

About the author

Heather Exner-Pirot is the director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.