This article originally appeared in the National Review.

By Aaron Wudrick, May 13, 2022

A long-running joke that perfectly encapsulates Canadians’ collective need to convince ourselves that our country is a linchpin of global affairs is that the domestic media always find a “Canadian angle” to any story in the news, no matter how tenuous the connection. This silly tradition has led to such important revelations as the fact that Donald Trump’s grandfather made his fortune in Canada by running a far from respectable hotel during the Klondike gold rush, or that Vice President Kamala Harris went to high school in Montreal.

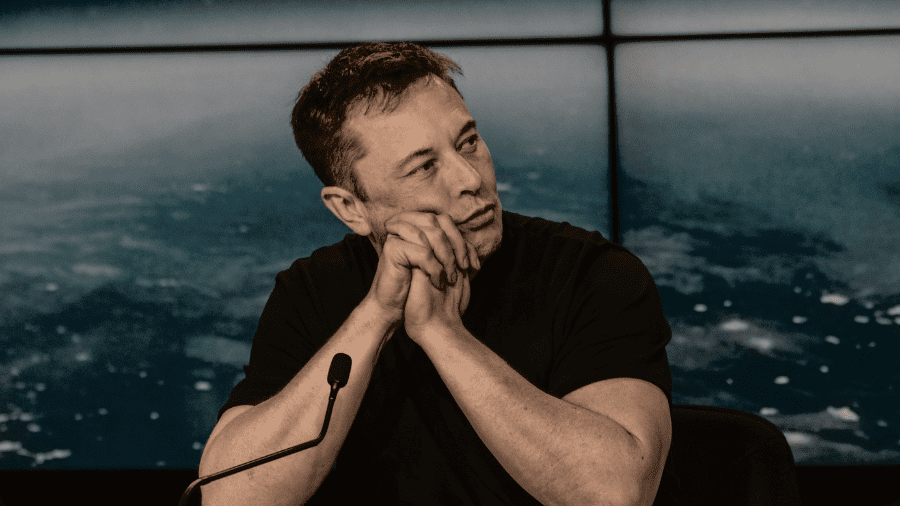

When it comes to the world’s richest man, however, there’s a legitimate Canadian angle. Elon Musk’s mother was born in Canada, which allowed him to apply for Canadian citizenship after finishing high school. Musk then spent a year living with a second cousin on the Canadian prairies — working on a farm, no less — and then two more attending Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, before transferring to the University of Pennsylvania. His first wife, Justine Wilson, and on-again-off-again partner Grimes are also both Canadians.

Indeed, the maple leaf is part of his story — and he still maintains at least a passing interest in what’s going on here, eh?

Musk’s recent purchase of Twitter has generated countless think pieces on everything from the appropriateness of rich people owning major platforms (are there any that aren’t owned by rich people?) to the Sisyphean struggle that surely awaits him (spaceflight and electric cars may be complicated, but have you tried moderating a discussion with 300 million people?). But speaking of a Canadian angle, here’s another one to consider: Hopefully the free-speech absolutist who believes that free speech is essential to a functioning democracy is aware of the alarming direction that Justin Trudeau’s government has been taking when it comes to regulating the Internet in Canada.

Consider a few recent examples.

First, the Trudeau government decided that it ought to concern itself with whether Canadians are watching enough Canadian content on the Internet. This is the impetus behind Bill C-11, which would extend the tentacles of the national radio and television regulator to policing social-media platforms. While regulating cultural content is nothing new in Canada — it even had a possibly defensible rationale in the pre-Internet world where cultural space was finite — it is simply ridiculous in present times, especially considering it may apply to both commercial-content providers such as Netflix and to user-generated content on platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

More recently the Trudeau government also tabled Bill C-18, which would force online platforms to compensate news-media outlets for sharing news content, including by simply posting links. That, of course, would create an absurdity in which the entities driving most of the eyeballs to struggling news websites are forced to pay for the privilege (an approach previously pursued by the Australian government, which led to Facebook temporarily blocking news pages in protest). Moreover, it wouldn’t do much for the credibility of Canadian media outlets that would benefit from this law, leaving them indebted to the government for strong-arming the tech giants into supplying them with some cash.

But perhaps most relevant to the proud new owner of a $44 billion social-media platform are the government’s as yet unfinalized plans to tackle “online harms.” This initiative began last year with a discussion paper that proposed creating a comprehensive system of online-content moderation and surveillance, complete with an Orwellian-sounding Digital Safety Commissioner holding the power to block websites.

The government then held consultations on the paper but refused to make the submissions public. Observers were left to marvel at the deficit of self-awareness required to hide feedback about a prospective censorship law.

Eventually a prominent law professor and critic of the government’s approach managed to obtain the full set of submissions through freedom-of-information laws. A glance at these submissions explains why the government wasn’t keen on releasing them. Groups that the Trudeau government might have assumed would be supportive — such as the LGBTQ, indigenous, and minority coalitions — instead raised concerns about the proposal, noting that such sweeping new powers could actually be deployed to squeeze out their voices rather than protect them.

The real capper, though, is the official submission from (pre-Musk) Twitter itself, which included this eyebrow-raising passage:

The proposal by the government of Canada to allow the Digital Safety Commissioner to block websites is drastic. People around the world have been blocked from accessing Twitter and other services in a similar manner as the one proposed by Canada by multiple authoritarian governments (China, North Korea, and Iran for example) under the false guise of ‘online safety,’ impeding peoples’ rights to access information online.

Having been sufficiently chastened, the Trudeau government has opted to appoint an expert panel to advise the government on how to move forward.

The good news is that it’s still entirely possible for the Trudeau government to abandon the approach outlined in its discussion paper in favor of a lighter touch: one that would be consistent with Musk’s own vision of self-regulation and avoid the obviously problematic approach of state moderation of content (beyond such well-established limits like libel and incitement to violence, which are already covered under existing laws).

Indeed, depending on the kinds of changes Musk implements at Twitter, he might provide a useful template for other platforms. Verifying users as human and focusing on defeating spam bots are at the top of his list. He might also consider banning autocratic governments that refuse to allow their own citizens on the platform.

Musk’s deal for Twitter is not expected to close until near the end of 2022, but he may be in de facto control of the platform much sooner than that. If he truly wants to make Twitter a beacon for free speech, he should keep an eye on what the Trudeau government is up to. And if it refuses to abandon its dangerous approach to online censorship, he should consider doing the principled thing and pull Twitter out of Canada.