This article originally appeared in the Vancouver Sun.

By Richard Shimooka, March 15, 2022

Two weeks into the invasion of Ukraine, the conflict risks expanding into a wider direct conflict between NATO and Russia. It’s not really a situation that many people have seriously contemplated for the past two decades, and probably requires some unpacking. Many have watched the tragic scenes coming out of Kyiv, Mariupol and Kharkiv and want the West to do more, but there are real limitations.

The most important factor is that NATO (specifically, the U.S., France and the U.K.) and Russia are nuclear-armed, which creates strong inhibitions for direct action against each other. This is why Pakistan, Iran and North Korea were so focused on obtaining such weapons — they ensure security and stability from foreign military threats.

For Russia, nuclear weapons — especially smaller “tactical” systems — are an important part of its defence strategy. Since the Gulf War, Russian military planners realized their inability to match NATO’s conventional capabilities. Consequently, they maintained a very large tactical nuclear weapons arsenal as a deterrent to adversaries. The possibility of a nuclear exchange exerts tremendous pressure on Western leaders to keep the conflict localized to Ukraine. As such, NATO establishing a no-fly zone over Ukraine remains a non-starter: It would put NATO aircraft in direct contact with Russian aircraft, potentially leading to escalation.

Instead, what have emerged are unspoken rules for the conflict. These norms and expectations largely arose in the half-century Cold War struggle between the West and the Soviet Union. Providing military arms and financial support to allies were generally tolerated. The Soviet Union supported their Communist allies like China, North Korea and North Vietnam against the U.S. or its proxies, while the U.S. did the same in Afghanistan and Central America during the 1980s. The Russians have continued in that tradition — one can recall reports that Russia had paid bounties to the Taliban for killing American soldiers.

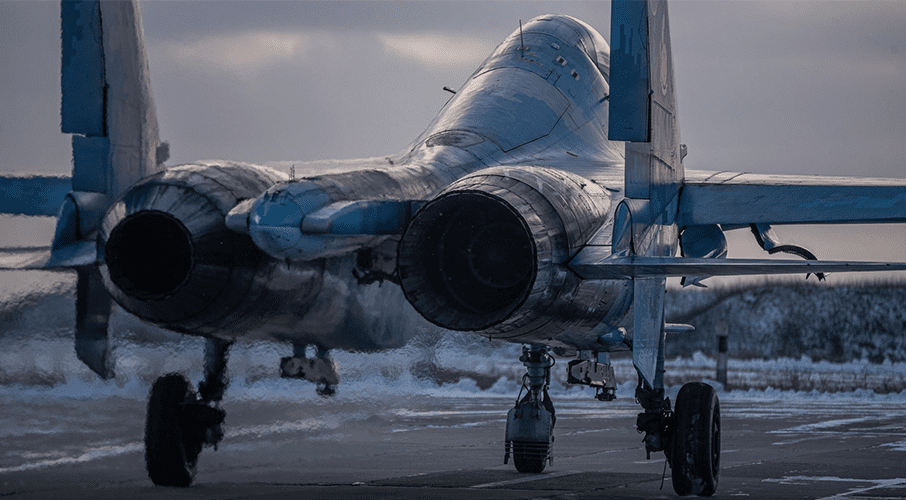

Ukraine has already received large infusions of Western weapons and military systems, such as anti-tank guided missiles that are critical for Ukraine’s ability to resist Russian forces. But there are, potentially, limits to what can be provided, as evident over the controversy in transferring Poland’s Mig-29s to Ukraine. While these aircraft might not make a substantial difference in the war, compared to the hundreds of millions of dollars in other military systems, they have become an important symbol for Ukrainians of Western military support.

Other norms have been formed during the conflict. One area is cyber-warfare, an area where Russia has been very active in the past. Early in the war, NBC News reported that U.S. President Joe Biden had been given options for the use of U.S. cyber weapons, which could potentially shut down Russia’s power, train and Internet systems. Up until this time, there has never been a leak about U.S. cyber weapons. Now, in the midst of this crisis, a “leak” disclosed their frightening capabilities. This represents a clear signal to the Russians that any cyber-war attack would be met with overwhelming force.

Yet this does not mean that the rules are clear, static or solid. There are risks involved with any course of action, and perceptions change. Historically, economic sanctions were generally considered an acceptable response, like in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military involvement in the Donbass region of Ukraine. However, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the West has levelled sanctions on an unprecedented scale — of a kind that have brought the world’s 11th largest economy to its knees and prompted Moscow to issue threats comparing these sanctions to acts of war.

This is problematic. If the war continues to go poorly for the Kremlin, the calculus of what is acceptable and unacceptable can change. Moscow may deem some currently acceptable aid as unacceptable tomorrow, either to lay blame for its failures and/or to change the dynamics on the ground. While the West must take care to avoid escalation, it also cannot cease aiding Ukrainian forces as they fight this invasion. It is a difficult balancing act — and failure to maintain the balance can result in an unbelievable tragedy for the people of Ukraine, or a thermonuclear war that will engulf our civilization.

Richard Shimooka is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.