This article originally appeared in National Review. Below is an excerpt from the article.

By Jon Hartley, March 14, 2024

As many are finally starting to realize across the world, the economic costs of a transition to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 is proving to be an extremely costly endeavor. The bills are only going to rise from here with costly regulation, highly expensive subsidies, and massive implications for the fiscal outlook with required taxes that would ultimately be levied on those below the median income as well as the rich.

Absent a dramatic improvement in energy-storage capacity, transitioning rapidly to an economy with only “renewables,” primarily solar and wind, simply doesn’t work as well as many hope (the wind doesn’t always blow and the sun does not shine) without reliable baseload power. This can come from either nuclear energy or from fossil fuels — of which the cleanest remains natural gas, which can also (despite worries about methane) operate as a bridge fuel between now and any completed transition. Letting the perfect be the enemy of the good is poor policy and reflects an environmentalism where dogmatism, not reason, is driving policy.

Environmentalists have a long record of opposing nuclear power, pointing to the difficulty of storing nuclear waste, the risk of the mishandling of nuclear materials, and the spillover effects of nuclear-power-plant disasters. Films such as Oppenheimer excited fears about how nuclear material in the wrong hands could have existential consequences.

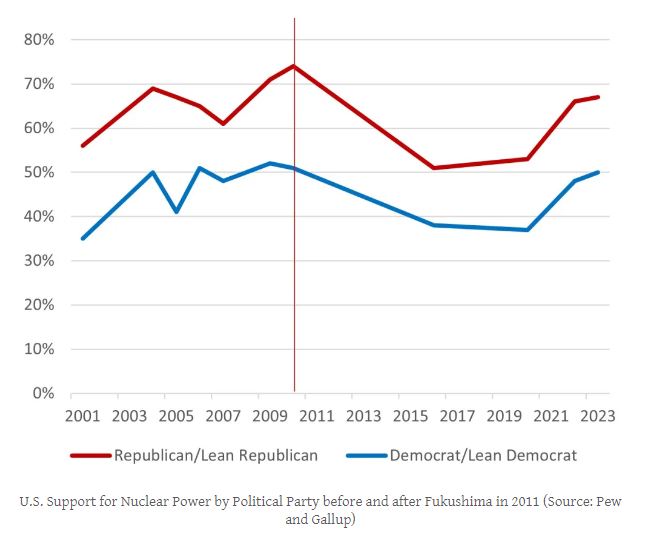

Opposition to nuclear power, a clean source of energy with no carbon emissions in its direct production, has, as mentioned above, a long history. While nuclear power was ascendant in the 1950s with the “Atomic Age,” fearmongering about nuclear goes back to the early days of the environmental movement in the 1960s. Advocates such as Ralph Nader and Jane Fonda reached peak influence with anti-nuclear protests during the 1970s and 1980s that involved anti-nuclear groups such as Friends of the Earth. (Anti-nuclear activism grew in Europe during this time as well, especially in Germany during the ’70s.) They helped advance the anti-nuclear movement by promoting false science around the dangers of nuclear power, making exaggerated claims about radiation exposure to those living near nuclear reactors, and so on. Since then, many environmentalists have been adamantly opposed to nuclear power as an energy alternative (although some of that has eased as their concerns switched to the climate). Democrats continue to be more opposed to nuclear power than Republicans are:

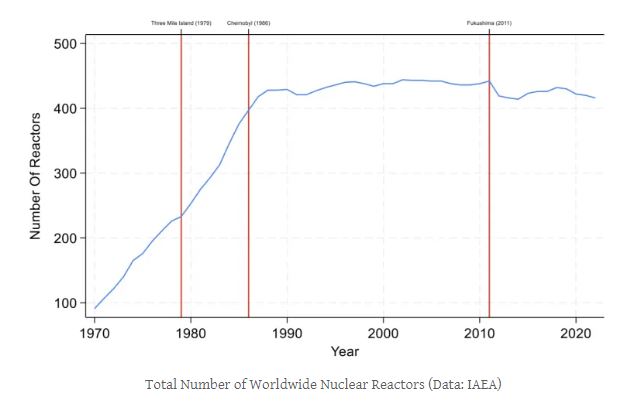

In a new working paper with Michael Manieri, I show how nuclear disasters such as Chernobyl and Fukushima have set nuclear-power growth back by decades by shaping attitudes toward nuclear power. Since Chernobyl in 1986, there have been extremely few new nuclear reactors built in America (save one in Georgia and one in Tennessee). The same is true largely for the rest of the world. Germany, one of the main centers of the European anti-nuclear movement, announced plans to phase out its nuclear-power stations at the turn of this century. This phaseout was slowed down after Angela Merkel took office but speeded up again after the Fukushima disaster in 2011. This deepened the country’s reliance on Russian natural gas (something it would later regret during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine) and, expensively, renewables. Japan itself shut down all of its nuclear reactors following Fukushima, although it began reactivating them in 2015. Russia and China meanwhile have been among the few countries still building nuclear reactors at some scale in recent decades:

Promisingly, there has recently been a resurgence in support for nuclear-energy development as a clean-energy alternative to fossil fuels amidst growing concerns about the role of emissions in global climate change. In 2020, the U.S. Democratic Party platform endorsed nuclear power for the first time since the 1960s. The California state government recently postponed the scheduled closure of Diablo Canyon, the last nuclear-power plant in California, until 2030.

Regulatory roadblocks to more nuclear development exist. For instance, small modular reactors (small mobile reactors with a fraction of the power capacity of traditional nuclear reactors, with much less fissile nuclear material) are currently under development by companies such as Oklo and NuScale Power that offer more safety, scalability, and economic benefits, while having received some initial approvals, have yet to get final approval from the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, creating enormous regulatory costs and delays for the companies.

***TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE, VISIT NATIONAL REVIEW HERE***