There is a price for Canada’s foreign and security policy autonomy, but because of Beijing’s own hesitance in upsetting its economic interests, it is not a high one, writes Luke Patey.

There is a price for Canada’s foreign and security policy autonomy, but because of Beijing’s own hesitance in upsetting its economic interests, it is not a high one, writes Luke Patey.

By Luke Patey, April 26, 2021

In a scene from the pre-COVID world in December 2019, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sat down for an interview in a crowded, bustling Italian restaurant in Montreal. Clinging on to power with a minority government, Trudeau’s Liberal Party had just survived a bruising election. But with Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou still under house arrest in Vancouver, and Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor enduring harsh conditions in Chinese prisons, CBC host Vassy Kapelos was also keen to ask the prime minister about Canada’s frayed relations with China.

Trudeau pointed out that Canada still had a “multifaceted, complex relationship with China.” Trade and investment stood on the one side, and human rights challenges on the other. After Kapelos pressed the prime minister on whether Canadians shared that nuanced perspective considering Beijing’s detainment of up to one million Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang and its political crackdown in Hong Kong, Trudeau retorted that she should “talk to our canola farmers,” “the lobster fishermen on the East Coast,” and “the cherry growers in the Okanagan.”

Despite recent polling showing that 73 percent of Canadians held an unfavourable opinion of China, agriculture industries benefitted from trade in the vast Chinese marketplace. “Canada is a trading nation,” Trudeau said, and Ottawa had to be careful in balancing standing up for human rights while creating mutual benefits through trade.

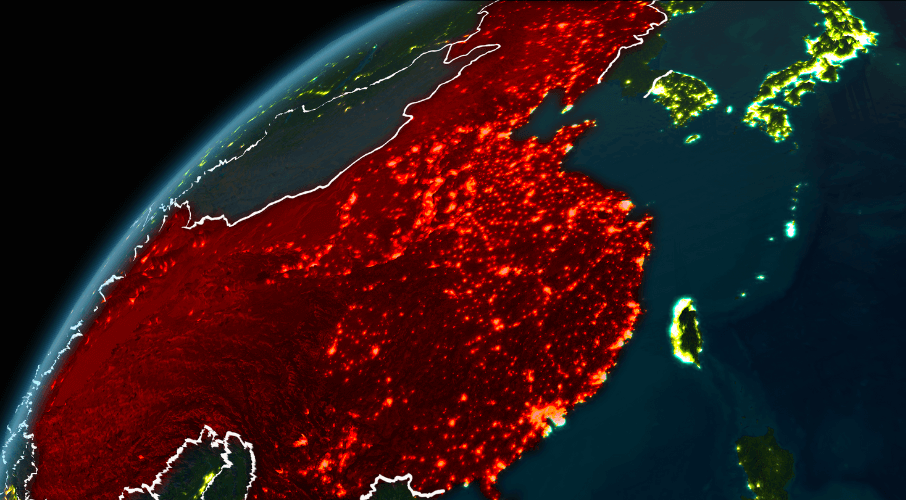

In Canada and the West at large, the debate on engaging China is often framed as one about balancing human rights with economic interests. Yet the black and white dichotomy is an unhelpful one. It drives forward the assumption that standing up for human rights, or for that matter, raising political and strategically sensitive issues with Beijing, will severely jeopardize Canada’s economic interests. The reality is quite different. China does have an increasing number of red lines it is busy policing. Whether on quelling international criticism on Xinjiang and Hong Kong or deterring international pushback against its militarization of the South China Sea, China employs coercive diplomacy to help shape the foreign and security policy decisions of other countries.

But the rupture in Canada’s relations with China has revealed the necessity to rethink entrenched narratives on Beijing’s willingness and capability to inflict economic harm. China may have risen to become Canada’s number two trading partner, but Canadian economic interests at large – and even those of the canola farmers, lobster fisherman, and cherry growers, as referenced by Trudeau – are in a stronger position to deal with China than many assume.

China has economic interests too. Trade is a two-way street. Investment can bring mutual benefits. Beijing remains sensitive to overly upsetting economic ties with Canada. Understanding Beijing’s limits in defending its political and strategic positions is instructive to Canada in shaping its foreign and security policy positions with China.

To be sure, China is an important trading partner for Canada. Representing 9.5 percent of Canada’s total, two-way trade in goods was over $100 billion in 2020, offering an important source of diversification from the United States. Not only is China a significant export market for Canadian agriculture goods and other natural resources, but Chinese foreign investment, tourism and higher education enrollment generate billions of dollars for the Canadian economy.

Yet China did not overly threaten Canada’s welfare and productivity when it targeted Canadian canola, pork and a long line of agricultural exports in 2019. There was a downturn in exports to China, and the canola industry was the biggest victim, losing an estimated $2.34 billion. But the significance of China’s trade measures and Beijing’s willingness to punish Canadian exporters is often exaggerated. Canada’s trade position as a whole held quite firm despite the pressure. Canada’s exports to China fell by almost $5 billion in 2019, but the loss only represented a tiny fraction of nearly $600 billion in total Canadian exports that year.

Canadian canola seed exports to China were halted after Beijing suspended the licences of two Canadian companies for alleged sanitary reasons. But the value-added products of canola seeds, oil and meal continued to find their way to China, with canola oil exports rerouted through the United Arab Emirates.

There was no guarantee that canola exports to China would have not fallen anyway. In 2018, one-third of imported canola was used as animal feed in China. But 40 to 50 percent of China’s pig population was devastated by the African swine fever, so their interest in Canadian canola may not have been high the following year. Beijing may have put Canadian canola on its restrictions list for the demonstrative effect alone, knowing that Canadian media would make a big deal of it (which they did) without overly upsetting Chinese interests.

Canada’s competitive agriculture industries and dominance as the world’s largest canola exporter also limited China’s ability to see through a widespread, long-term ban. It took only a few months before China lifted restrictions on Canadian pork due to domestic shortages. With food security concerns spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic, Beijing ramped up its purchases of Canadian canola once again. Canadian canola farmers “watched in surprise and delight” as prices rose sharply from August 2020 on the back of Chinese and global demand.

Neither did Beijing impose trade measures that upended the work of Canadian lobster fishermen on the East Coast or cherry growers in the Okanagan Valley. Quite the opposite, Canadian lobster exports to China boomed during the diplomatic crisis. The glad-handing and frequent visits of then Nova Scotia premier Steve McNeil to China may have encouraged commerce, but Chinese tariffs on Maine lobster in response to President Donald Trump’s trade war likely played a stronger role in boosting Canadian exports. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, McNeal’s charm offensive could not overcome Chinese worries that the virus could be transmitted through seafood, resulting in new Chinese border measures on Nova Scotia lobsters.

As for Canadian cherry growers, Canada’s fresh fruit exports remained healthy throughout the diplomatic row. Indeed, British Columbia farmers were also successful in tapping into China’s e-commerce networks. In any case, Canadian fruit exports, similar to its overall trade, are overwhelmingly dependent on the American market.

Canada’s experience with China’s economic coercion is not out of ordinary. In 2010, after the Nobel committee in Oslo awarded the Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, an imprisoned Chinese intellectual and human-rights activist, Beijing placed a six-year diplomatic freeze on Norway and cut off its salmon exports to the Chinese marketplace. Norway lost up to US$1.3 billion in its exports to China between 2011 and 2013, but this only amounted to a drop of 0.3 percent in its total annual exports. Similar to Canadian canola oil, Norwegian salmon was rerouted through Vietnam during the long-running dispute. Norway’s trade with China even reached new highs by 2015.

More recently, after calling for an international investigation into the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic early last year, Australia faced China’s barrage of tariffs and restrictions on its coal, wine, barley timber, and other exports. But after a year, the damage was minimal. Similar to China’s short-term difficulty in staying away from Canadian canola, Beijing did not place trade measures on Australian iron ore exports, which grew strongly in 2020, due to demand from China’s construction stimulus. For other targeted products, the fungibility of natural resources resulted in Australian coal and barley finding new markets in India, Japan, and the Middle East.

Australia’s wine industry is suffering. The iron ore boom may not last. And just as with Canada and Norway, Australian exports could have done better if China had not placed trade restrictions. But there is a price for foreign and security policy autonomy, and because of Beijing’s own hesitance in upsetting its economic interests, it is not a high one.

Neither has China shown any willingness to deploy what probably represents its most potent trade weapon: restricting Chinese exports to Canada and other targeted countries. As argued in a recent analysis by Global Affairs Canada, Canadian welfare and productivity benefits from essential Chinese imports such as laptops, cell phones, consumer goods, and more recently during the pandemic, face masks. But blocking these products from entering foreign countries will undermine economic growth and jobs back in China.

Over two years have passed since the diplomatic crisis between Canada and China began, with Meng’s extradition case still ongoing, and Kovrig and Spavor facing espionage charges in China. Ottawa remains in a difficult spot in responding to Beijing. But any hesitance on the part of the Canadian government in placing new pressure on China to settle the dispute should be done knowing the limitations of China’s economic coercion.

Ottawa could continue to work with countries that signed its recent declaration against arbitrary detention to include political sanctions on those countries, such as China, which violate international law. Australia, Sweden, and other countries also have citizens detained in China on political grounds. Even if the Kovrig and Spavor cases are resolved successfully, China’s use of arbitrary detention will not go away unless there are clear detrimental consequences to its broader interests.

Beijing will likely retaliate to any Canadian action, but to minimize any economic harm done to selected industries, Canada can continue to broaden its horizons by diversifying its agricultural exports to India, Southeast Asia, and other emerging markets. Diversification does not entail decoupling from China, but pinpointing which industries are prone to Beijing’s pressure, and encouraging new trade and investment to lower such strategic vulnerabilities. Canada can also exchange lessons learned with Australia on how targeted countries are coupling long-term export diversification strategies with short-term finance facilities and political risk insurance.

In a post-pandemic world, China’s economic coercion will only go away if Ottawa and its partners find the strategic clarity to see through China’s own limitations and muster a concerted response. Shelving outdated narratives of the necessity to balance economic interests with human rights represents a first important step.

Luke Patey is a senior researcher at the Danish Institute for International Studies and the author of How China Loses: The Pushback Against Chinese Global Ambitions.