The provinces’ preoccupation with the size of federal cheques during the prelude to this week’s health ministers meeting reveals a failure to learn the lessons of the past 12 years, writes Sean Speer.

By Sean Speer, Oct. 18, 2016

INTRODUCTION

This week’s meeting of federal, provincial, and territorial health ministers should be about how to reform Canada’s health-care system. We certainly need it. Not only does Canada rank poorly with regards to wait times and access to doctors and medical technologies relative to most of our peers, we also have one of the most expensive health-care systems in the industrialised world. Reform is thus needed to improve the affordability, universality, and quality of Canadian health care.

Yet the meeting is shaping up to regard reform as a secondary matter and instead focus on federal-provincial squabbling about how much Ottawa sends to provincial capitals to maintain the status quo. A preoccupation with the size of federal cheques reveals a failure to learn the lessons of the past 12 years. The record shows that less funding with fewer strings is the best impetus for real reform.

Yet the meeting is shaping up to regard reform as a secondary matter and instead focus on federal-provincial squabbling about how much Ottawa sends to provincial capitals to maintain the status quo. A preoccupation with the size of federal cheques reveals a failure to learn the lessons of the past 12 years. The record shows that less funding with fewer strings is the best impetus for real reform.

Rarely are policymakers able to draw from clear and applicable examples in devising solutions to present-day problems. Health-care reform is an exception.

The past dozen years provide a valuable case study on the interplay between Ottawa and the provinces on the health-care file and the type of federal involvement that contribute to or detract from reform. Federal Health Minister, Jane Philpott, would be wise to study it in advance of Tuesday’s meeting.

10-YEAR HEALTH ACCORD: “THE MONEY DID NOT GO TO CHANGE”

This period is marked by two distinct models for federal leadership with regards to health-care reform. The first is characterized by the then-Martin government’s 10-year health accord that involved the provincial adoption of federal priorities in exchange for considerable new funding including a new 6-percent annual escalator to the Canada Health Transfer. The much-vaulted agreement was supposed to be a “fix for a generation.”

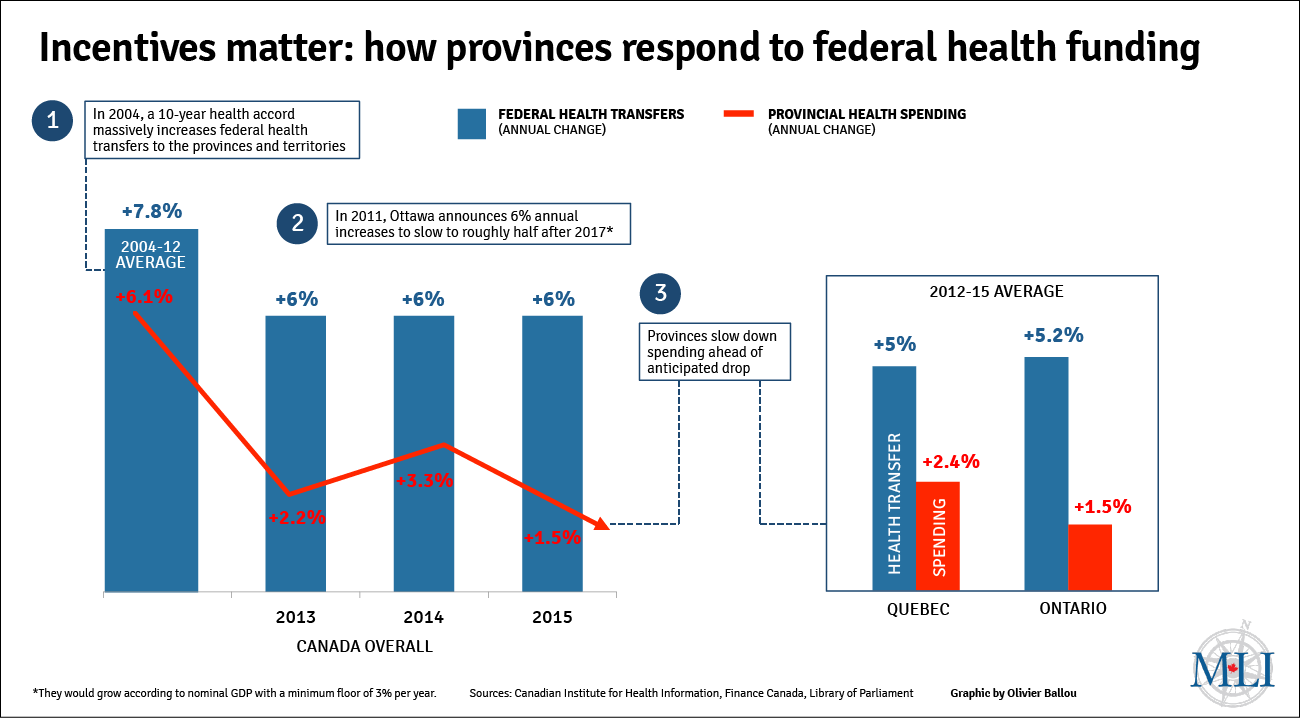

And yet the health accord failed to catalyse reform. Buttressed by massive new federal dollars, annual provincial spending on health care grew, on average, by 7.8 percent between 2004 and 2012. But this new spending did not translate into better results. Wait times grew. Our relative performance fell. And health-care spending continued to consume more and more of provincial budgets.

The record shows that less funding with fewer strings is the best impetus for real reform.

Why did the health accord lead to more spending but not meaningful reform? Former Saskatchewan finance minister Janice MacKinnon points to the increase in federal funding. More federal dollars papered over the health-care system’s inherent weaknesses and diminished the need for provincial governments to enact reform. Saskatchewan shelved a sensible plan to consolidate hospitals because of the infusion of federal funding as one example. As MacKinnon puts it: “Why would you make a tough decision if somebody is going to give you more money to keep the status quo? … The money did not go to change.”

PROVINCES KNOW BEST: THE “RIGHT CONVERSATION”

The second period begins with Jim Flaherty’s announcement in December 2011 that the then-Harper government would not negotiate a new health accord (when the previous one expired in 2014) and intended to slow the annual growth of the Canada Health Transfer from 6-percent per year to tied to economic growth (with a 3-percent floor) beginning in 2017.

The underlying assumption was that the provinces and territories were best placed to drive reform and that Ottawa’s main contribution was to provide clear, predictable funding with fewer conditions. But instead the government was accused of abandoning health care and in turn undermining the prospect for reform. Ontario’s finance minister even called the December announcement “a lump of coal.”

The subsequent experience tells a different story. The federal decision prompted renewed interest in provincial-led reform. A premier-level working group on health-care innovation was established in the following weeks. New arrangements on bulk drug purchases were launched. Greater attention to cost containment became evident. Slow yet steady progress in the direction of health-care reform has commenced. The right conversation – focused on reform instead of interjurisdictional infighting about funding – was started.

Just consider: provincial and territorial health-care spending is now growing slower than the Canada Health Transfer. Total provincial and territorial spending has grown by an average of 2.5 percent annually since 2012.

Ontario’s experience is a prime example. Its annual health-care spending has grown, on average, by 1.5 percent over this period, and in the most recent year the growth in its federal transfer payment is projected to be twice as large as the year-over-year change in provincial spending.

The key takeaway is that provinces and territories are capable of spending control and structural reform with the right incentives. Their spending behaviour changed in response to the knowledge that Ottawa would not be coming to the negotiating table and intended to adjust federal transfer payments over time. It is a powerful reminder that incentives matter when it comes to fiscal federalism and creating the conditions for health-care reform.

NEW ROUND OF HEALTH-CARE NEGOTIATIONS: WHAT COMES NEXT?

Which brings us to this week’s meeting between Minister Philpott, and her provincial and territorial counterparts.

The Trudeau government was elected on a commitment to restore “federal leadership” in health care, including providing additional funding and signing a new health accord. The provinces and territories were relieved. New federal dollars would let them defer tough choices, particularly with a series of 2017 and 2018 elections across the county.

But since then Minister Philpott has talked about the need for “structural reform” and the inherent risks of “throwing money at the problem.” She has even said that Ottawa does not intend to revisit its predecessor’s changes to the Canada Health Transfer’s growth rate.

Provinces and territories are capable of spending control and structural reform with the right incentives.

The provinces are fussed to say the least. The premiers have sent a letter to the prime minister demanding a meeting. Provincial spokespeople are now lowering expectations for this week’s meeting. The discussion seems poised to devolve into a conflict about inputs rather than outputs (or “money and not people” as the Canadian Medical Association president has recently put it).

Ottawa’s commitment to meaningful reform will invariably be tested. More federal funding may buy provincial approbation but the past 12 years show it is unlikely to secure patient-oriented reform. Tuesday’s meeting is therefore a critical juncture.

CONCLUSION

While Canada’s health-care system is among the most expensive in the world, its outcomes are far from world leading. Canadians can and should demand better, and Minister Philpott has rightly made the case for reform.

The question is: which path will she choose to get there when she meets with her provincial and territorial counterparts this week? The last 12 years present two clear options.

Real federal leadership is about creating the incentives for provincial-led reform, and that starts with resisting calls for more dollars. We wish the minister luck.

Sean Speer is a Munk senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.