This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, September 28, 2023

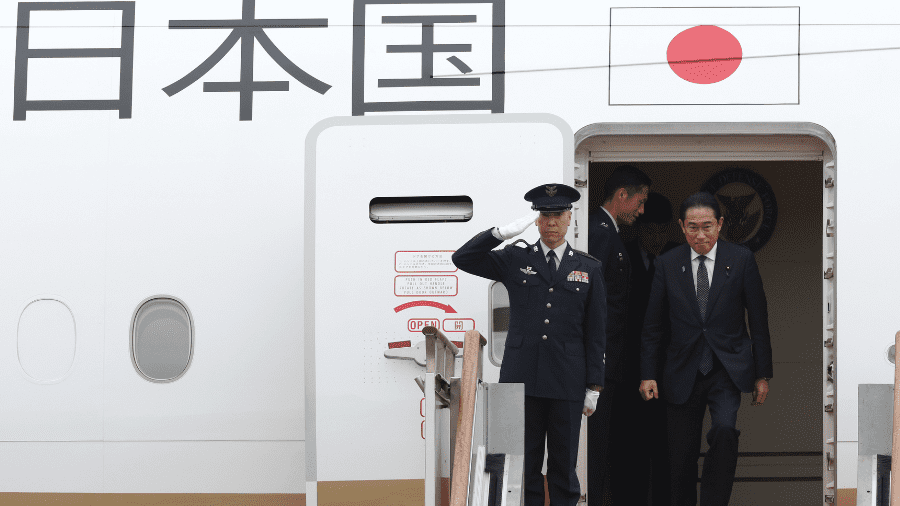

Since Fumio Kishida became prime minister, Japan has experienced and seen significant changes on the domestic and international fronts.

Under Kishida’s watch, Russia has invaded Ukraine, there are heightened tensions due to North Korea’s missile testing, an increasingly assertive China and a domestic economy that is facing inflation for the first time in decades.

A sober assessment of Kishida’s first two years is a litmus test of the sustainability of his leadership.

On the domestic front, we should examine his economic achievements. Upon coming to power, he soon introduced his “new capitalism” policy framework, sometimes dubbed Kishidanomics. Most analysts noted Kishidanomics’ focus on income redistribution, fair minimum wages, bolstering social security services and reducing the wealth gap. Critics have argued that the effects of these policies have been uneven and some suggest that not enough has been done to stimulate the nation’s stagnating economy.

Have there been tangible benefits for the Japanese economy?

The answer to that question is that it depends on what part of the economy you belong to. Real wages are stagnant despite a tight labor market. This impacted the average person when key consumer prices rose 3.1% in September 2023. Moreover, Kishida’s administration has yet to implement a workable response to the 2023 World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report in which Japan ranked 125th out of 146 countries in terms of gender parity — the lowest among the Group of Seven countries and low compared to other nations in the East Asia and Pacific regions.

Recently there have been discussions on the creation of special business zones for asset management companies with the aim to encourage overseas players to set up shop in the country. The problem with this approach is that it is really just old wine being presented in new bottles. Aside from high taxes, investment in Japan, or the lack thereof, stems from an aggregate of factors including capital gains laws, an overly regulated business environment, a lack of international schools when compared to Hong Kong or Singapore, as well as other perks such as a liberal domestic helper system.

In short, Japan’s long-term domestic challenges seem to be inherited by one administration after another with incremental and uneven progress advanced by each. But on other fronts, such as with foreign policy, security and defense, these have been areas where Kishida has achieved tangible success.

A good example of a success for the administration, however moderate, can be seen in Japan’s approach to climate change. Kishida has made climate change a key part of his foreign policy agenda, pledging to make the nation carbon neutral by 2050. His administration has also played a crucial role in international climate change negotiations, contributing to the success of the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

Kishida has also been adept in terms of diplomacy in at least four areas: the war in Ukraine, the Taiwan issue, development aid in Southeast and South Asia, as well as the Pacific Islands region and resuscitating Japan’s relationship with South Korea.

First off in Ukraine, Kishida has repeatedly warned that today’s Ukraine could become the Indo-Pacific’s future. The explicit linkage of Russia’s war and invasion there and the associated downstream consequences has raised the importance of the Indo-Pacific region.

Second, based on strict adherence to Japan’s “One-China” policy, we have seen Tokyo advocate for peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait in multilateral meetings and statements. The Kishida administration has stressed the importance that Taiwan represents to the world’s technological supply chains, such as with semiconductors, its geographic centrality as it pertains to sea lines of communication that ferry $5.5 trillion in trade and its strategic position in the first island chain and Japan’s security.

Third, the Kishida administration continues to champion infrastructure and connectivity development in developing countries situated in the Pacific Islands and elsewhere such as Southeast Asia. By way of example, the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) update in March expanded the geographic location of where Japan is supporting development through infrastructure and connectivity projects.

Stressing the fundamental concept of its Free and Open Indo-Pacific policy, Japan continues to invest in the Indo-Pacific region with the aim of fostering prosperity, a place that values freedom and the rule of law and is free from coercion and force.

Kishida’s revamped FOIP vision prioritizes defending freedoms and the understanding that countries that are vulnerable due to developmental challenges are in greatest need of the rule of law. To achieve that, the Kishida administration has emphasized the importance of respect, diversity, inclusiveness and openness. According to his vision, no one should be excluded, there should not be any factions or camps, values shouldn’t be imposed on others, rule-making must be achieved through open dialogue, there should be an equal partnership among all nations and an approach that puts people first.

These initiatives are clearly meant to contribute to improvements in such regions, but also are part of a larger effort to ensure that China does not use the Belt Road Initiative to cultivate relations and and garner votes in the United Nations and further support among the Group of 77 developing nations, as well as other multilateral groupings. The fear is those governments could aligned behind China and advance its preference for a less rules-based world that prioritizes so-called sovereignty, noninterference and interpretations of the rule of law, democracy and human rights that are defined by Xi Jinping and his government.

Fourth, and still a work in progress, is the Japan-South Korea relationship. Working with South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, Kishida has moved the relationship into a more constructive dynamic focusing on shared interests. Key areas of improvement were evidenced in the recent Camp David Principles that committed the two neighbors to trilateral military drills, increased diplomatic contact, partial semiconductor relocation cooperation and finding diplomatic and unorthodox ways to depoliticize historical disagreements, including the so-called comfort women and forced labor issues. More needs to be done.

However, the administration’s efforts with China have been less successful. The relationship between the second and third largest economies remains rocky, as evidenced by the disinformation campaign following the release of treated water from the damaged Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant; barring the exit from China of prominent executives of Japanese firms there; and the continued greyzoning and other pressures placed on Japan in the East China Sea. Tensions will undoubtedly increase as Beijing misinterprets all of Tokyo’s moves to enhance Japan’s security through a lens that interprets such actions as being linked to U.S. efforts to contain China and engage in regime change.

Two years on, Kishida continues to embody stability in terms of leadership and a balanced tone towards China, while deepening its deterrence and economic resilience with like-minded partners like the U.S. More needs to be done on the domestic front in terms of sustainable wage increases, addressing gender and diversity challenges and making Japan a more attractive place for foreign investors.

Dr. Stephen Nagy is a professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute; a senior fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute; and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.