MLI offers the first-ever comprehensive assessment of Canada’s criminal justice system

OTTAWA, Sept. 21, 2016 – Canada is suffering from a “justice deficit” – a large and growing gap between the aspirations of the criminal justice system and its actual performance.

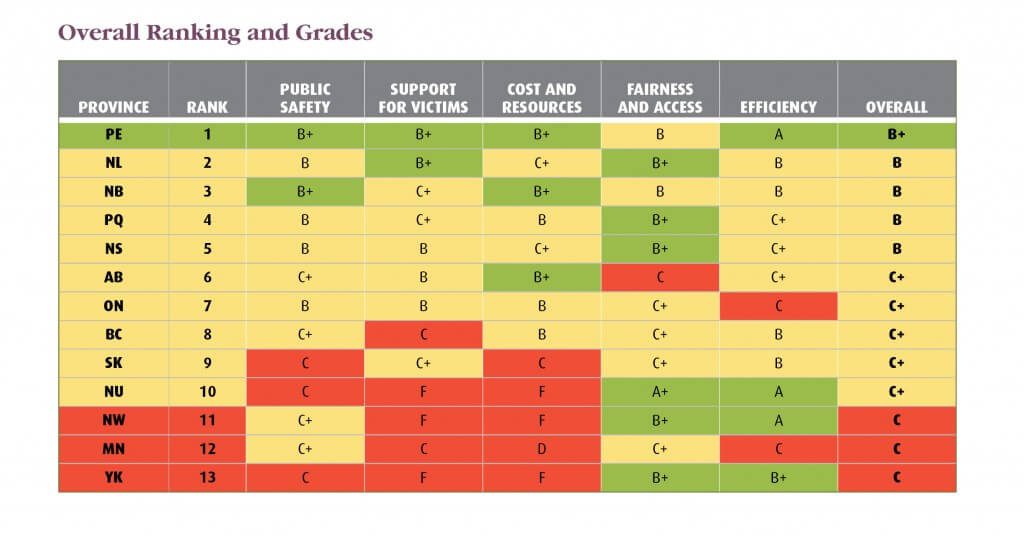

That’s the main conclusion from MLI’s inaugural Report Card on the Criminal Justice System. Following an extensive data-gathering effort, authors Benjamin Perrin and Richard Audas have rated the provincial and territorial justice systems according to public safety, support for victims, cost and resources, fairness and access, and efficiency.

For the full report, click here.

For the justice report card interactive graphic, click here.

The report finds that, with few exceptions, our justice system is slow, inefficient, and costly.

“It is our hope that this first criminal justice system report card will generate tough questions for the many actors responsible for administering the justice system in each of these jurisdictions, enhance the collection of key data on its performance, and spur much needed reform”, write the authors.

The Supreme Court sent a similar message in its July 8, 2016 decision in R v. Jordan when it threw out drug trafficking charges from British Columbia; more than four years had elapsed from when the accused was charged to the conclusion of the trial. In its decision, the court decried what it called a “culture of delay and complacency”.

But until now, the extent of inefficiency and underperformance in the Canadian criminal justice system has never been fully assessed.

The Macdonald-Laurier Institute Report Card on the Criminal Justice System aims to enhance accountability and transparency with a view towards its reform and ongoing improvement for the benefit of all Canadians. The authors assess each province and territory’s criminal justice system using data averaged over the most recent years and quantitative statistical methods.

This process revealed excellent results in certain jurisdictions on some key metrics, but some appalling failures in other instances such as excessive delays in time to trial, inadequate support for victims of crime, large proportions of cases stayed or withdrawn, very high crime rates in some jurisdictions, poor rates for solving crimes, soaring costs of policing, and disappointing rates of Aboriginal incarceration.

There was a wide degree of variability on every metric. And while there are some regional trends, some provinces and territories do noticeably better or worse within their respective regions.

There was a wide degree of variability on every metric. And while there are some regional trends, some provinces and territories do noticeably better or worse within their respective regions.

The Atlantic provinces and Quebec generally scored better than the Western provinces and the territories. Perhaps surprisingly, some larger and more prosperous provinces such as Ontario and British Columbia fared relatively poorly, with C+ grades and significant areas needing improvement. Every jurisdiction has room for improvement in reaching some or all of the core objectives of the justice system, and in numerous instances, urgent reform is required.

A few of the highlights from the report cards for each province and territory are:

- The cost of public safety per person is lowest in Quebec, Ontario, and British Columbia, while it is highest in the territories, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

- The territories have disproportionately high per-capita crime rates – far exceeding any of the provinces. Among the provinces, violent crime rates per capita are highest in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Newfoundland & Labrador, while they are lowest in Ontario, Quebec, and Prince Edward Island.

- Public perceptions of the police are generally higher in the Atlantic Provinces than in the Western Provinces.

- There are serious issues with efficiency in Ontario’s justice system. It has the worst record in Canada for the proportion of charges stayed or withdrawn (43.1 percent on average), compared with a mere 8.6 percent in neighbouring Quebec. At just 55.3 percent on average, Ontario is also a significant outlier for the percentage of accused persons found guilty.

- British Columbia received a failing grade for its weighted clearance rate for violent crime (on average slightly over half of violent crimes were solved by police).

- In terms of support for victims, restitution orders (where offenders are required to compensate their victims) are infrequent in Canada and ordered in less than 1.0 percent of cases in Quebec, Manitoba, and Nunavut.

- Disproportionate levels of Aboriginal incarceration relative to the population are a problem in every jurisdiction in Canada, but are particularly acute in Alberta, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and British Columbia.

“Canadians deserve a constructive response from those responsible, including the police, Crown prosecutors, courts, governments, corrections authorities, victim services officials, and others”, write Perrin and Audas. “As has been said, it is not a legal system that we need, but a justice system”.

***

Benjamin Perrin is an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia, Peter A. Allard School of Law and a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute for Public Policy. He is a Faculty Associate at the Liu Institute for Global Issues and the Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies.

Richard Audas, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Health Statistics and Economics at the Memorial University, Faculty of Medicine.

The Macdonald-Laurier Institute is the only non-partisan, independent national public policy think tank in Ottawa focusing on the full range of issues that fall under the jurisdiction of the federal government.

For more information, please contact Mark Brownlee, communications manager, at 613-482-8327 x105 or email at mark.brownlee@macdonaldlaurier.ca.