This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Bruce Pardy, August 25, 2023

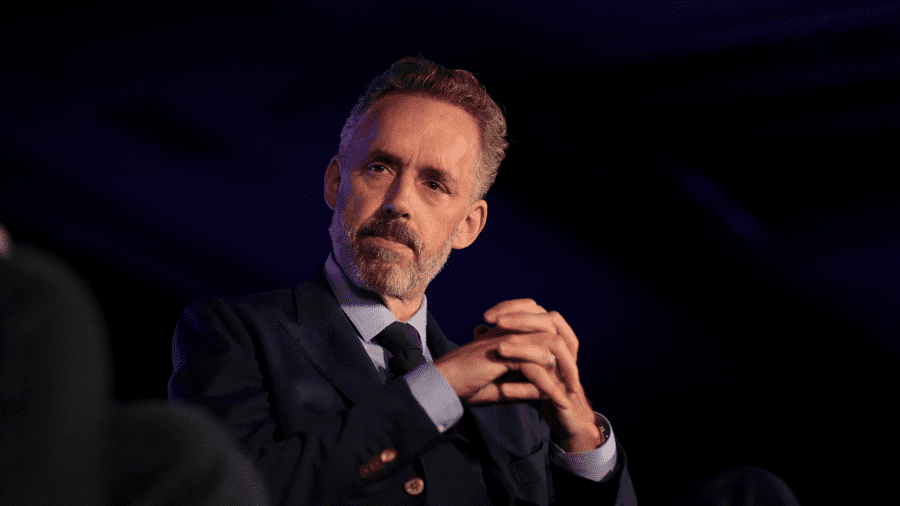

The Ontario College of Psychologists can re-educate Jordan Peterson. So said the Ontario Divisional Court on Wednesday. In November 2022, the College ordered Peterson, a prominent public intellectual and emeritus University of Toronto psychology professor, to undergo remedial education because of statements he made on social media. Peterson argued that the order infringed his freedom of expression. But the Divisional Court deferred to the college, a body created by provincial legislation, concluding that the order was a reasonable exercise of the regulator’s authority. In the era of judicial deference to the administrative state, constitutional rights do not mean what many Canadians think they mean.

The Supreme Court of Canada is largely to blame. In most circumstances, regulatory bodies are not required to apply the law correctly, the Supreme Court has said, but only “reasonably.” In other words, in certain contexts a regulator can be legally wrong if it is not unreasonably wrong. “’Administrative justice’ will not always look like ‘judicial justice’,” the court wrote in 2019 in its leading administrative law case, Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v. Vavilov, “a court … does not ask what decision it would have made in place of that of the administrative decision maker … or seek to determine the ‘correct’ solution to the problem.”

But the story gets worse. In cases involving the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, regulatory bodies can infringe charter rights if they do so “proportionately.” In its 2012 decision in Doré v. Barreau du Québec, the Supreme Court said that regulators must balance charter protections against the statutory objectives the regulator is attempting to achieve. Where a court is reviewing a decision that may infringe a charter right, as in the Peterson case, regulators are entitled to deference if the decision “falls within a range of possible, acceptable outcomes.”

And it is even worse than that. The court has enabled regulatory bodies to ignore charter rights altogether if they instead balance imaginary “charter values,” mentioned nowhere in the text, by which they mean progressive ideals such as equity, social justice and group dignity. In 2018, for instance, the court allowed the law societies of Ontario and British Columbia to refuse approval of Trinity Western University’s proposed law school because of its religious community covenant, allowing the regulators’ pursuit of equity in the name of public interest to obliterate freedom of religion.

Our government was not supposed to work this way. In principle, the administrative branch is powerless except for specific statutory mandates. Judicial review supervises government agencies, including professional regulatory bodies, to ensure they remain within those legislated powers. “I know of no duty of the court which it is more important to observe, and no powers of the court which it is more important to enforce, than its power of keeping public bodies within their rights,” wrote Lindley M.R. in an 1899 UK case. “The moment public bodies exceed their rights they do so to the injury and oppression of private individuals.”

But the legal ground has slowly shifted beneath our feet. We have moved away from the rule of law back towards rule by executive fiat. Judicial deference grants control not to a monarch but to a professional managerial class. Broad discretion in the hands of administrative bodies has become the foundation of our modern system of government.

Deference from the courts makes regulatory witch hunts possible, when carefully crafted in the guise of “unprofessional conduct,” “civility” or “undermining public trust in the profession”. Professional regulators can turn their focus from ensuring competence and ethical practice to political compliance. In Peterson’s case, complaints did not come from clients nor relate to his psychology practice, which he ceased in 2017. Instead, they largely targeted Peterson’s tweets on political topics such as Justin Trudeau and his chief of staff, an Ottawa city councillor, the climate change agenda, and transgender activism.

Under the College’s order, Peterson must pay for the remediation himself. The sessions will end when the “coach” determines that Peterson is appropriately re-educated. Yet the College insists that the order is not disciplinary. In fact, the college’s committee did not conduct a disciplinary hearing and never concluded that Peterson committed professional misconduct. Nevertheless, the college has promised that failing to complete the program may result in an allegation of professional misconduct and the commencement of actual disciplinary proceedings.

In principle, remedies and punishments are to be imposed only after a matter has been adjudicated and an accused found guilty. But courts have deferred to regulators in this respect as well. And the practice is growing. The Law Society of Ontario proposes to give its Proceedings Authorization Committee similar powers to require lawyers to submit to re-education, even if the committee concludes that there are no grounds for a disciplinary hearing.

Peterson is not alone. Across the country, regulators are becoming ever more insistent on ideological concurrence. Law societies are instituting politically laden “cultural competence” requirements. Medical regulators have sanctioned doctors for expressing medical opinions contrary to approved COVID narratives. Nurses and teachers cannot safely voice doubts about transgenderism or “anti-racist” agendas inside their institutions. Deference empowers the tyranny of the administrative state.

Bruce Pardy is executive director of Rights Probe, professor of law at Queen’s University and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.