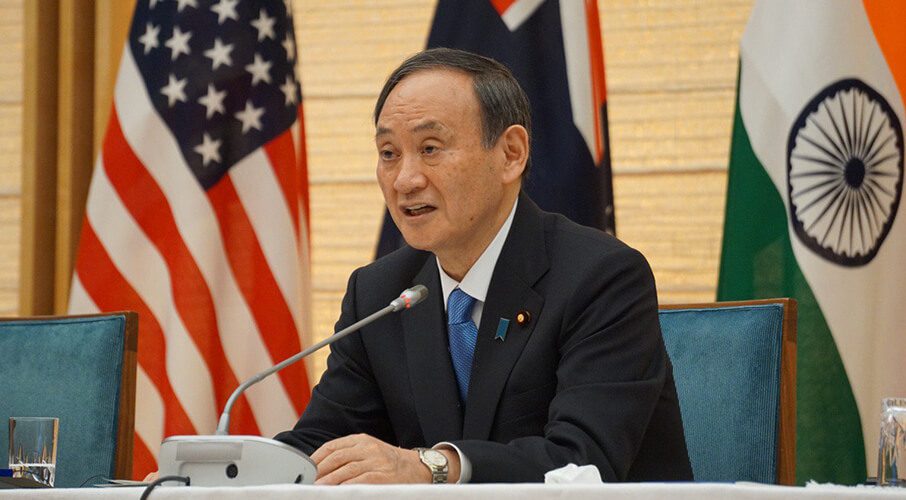

We are only at the beginning of Japan’s leadership role in the Indo-Pacific, writes Matthew Neapole. Expect even bigger things from Japan in the future.

We are only at the beginning of Japan’s leadership role in the Indo-Pacific, writes Matthew Neapole. Expect even bigger things from Japan in the future.

By Matthew Neapole, May 31, 2021

The recent talks between Chinese and American officials in Anchorage, Alaska, were preceded by both sides trading in fittingly icy and prickly barbs during their opening statements. Many of these centred on the domestic situation in China, or the Chinese rebuttals to these charges. In March, Chinese Foreign Policy Spokesman Zhao Lijian delivered some of his own, likening ally Japan to a vassal state of the United States.

However, Japan is increasingly becoming an ever-more critical hinge for like-minded partners in the Indo-Pacific region. Importantly, irrespective of the differences in its interpretation, the Indo-Pacific framework is growing in importance and centrality to how Western democratic states envision the region. In many ways, Japan as an actor has somewhat fallen out of vogue in the policy analysis surrounding the region, thanks both to its “Lost Decade” and the concurrent meteoric rise of China. However, recent developments indicate that Japan is regaining its strategic importance and, importantly, agency of its own. There are a few reasons for this.

First, the concept of the Indo-Pacific – specifically, Japan’s vision of a “Free and Open Indo Pacific” (FOIP) – is becoming increasingly authoritative. This concept is unequivocally Japanese in origin, being spearheaded by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2007, and places Japan very close to the nexus of action. As time has passed, this concept has gained in popularity and traction among Western states, including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. The EU itself has also recently published its own Indo-Pacific Strategy for Cooperation. Notably, the United States has also devoted a great deal of energy into reframing its policies to incorporate an Indo-Pacific bent, and there is interest in the concept brewing in other states, such as Canada.

That being said, there are two camps as far as tone in Indo-Pacific approaches is concerned: adversarial or competitive. The adversarial approach can be best seen with how the United States has treated the region, particularly the Trump administration’s approach to China – though one could argue this has roots in the Obama administration’s “Asia Pivot.” However, as demonstrated by the meeting in Alaska under the newly minted Biden administration, there seems to be a continuation in general policy, if not rhetoric, from the previous administration.

The Japanese strategy is a good example of the competitive camp – one that acknowledges the challenge that Beijing represents but does not frame it in too confrontational a manner. This approach is often more appealing to other actors, particularly those who have a great deal of economic exposure to China. This will make Japan a more like-minded partner to others in the region when dealing with China, while serving as an inclusive building block for minilateralism. Furthermore, Japan’s centrality when it comes to this concept will also transfer over to its role in dealing with allies and partners in the region.

Second, Japan has developed a complex, deep, and longstanding relationship with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and its members. Historically, this was built up primarily through constructive aid partnerships and beneficial trading regimes instituted by the Japanese government. For example, Japan remains one of the largest aid donors to ASEAN states, as well as being an active contributor through its own development bank, the Asian Development Bank (ADB). In fact, it was the ADB that forecasted the oft-quoted figure that Asia required roughly US$1.5 trillion in annual infrastructure investment until 2030. Furthermore, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – a massive ASEAN-focused free trade agreement involving Australia, China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, and ASEAN – is another vector Japan has pursued to deepen economic ties in the region.

ASEAN, though at times dysfunctional, is nevertheless buoyed by the increased economic and strategic interests in the region and may eventually develop more complex institutional frameworks. Japan’s geographical, historical, and institutional expertise with ASEAN will be invaluable for non-members without this experience. ASEAN is also poised to become a focal point due to its geostrategically commanding position in the Indo-Pacific. In fact, ASEAN itself has at least signalled interest in the Indo-Pacific strategy, having published its Outlook on the Indo-Pacific in 2019. And, as previously mentioned, the EU has also published an Indo-Pacific strategy that even stresses the centrality of ASEAN to its goals.

Third, the Trans-Pacific Partnership brought together various interested trading nations in the Pacific. However, negotiations advanced until they crashed into turbulent waters when the United States withdrew from it in 2017. In the midst of this uncertain situation, Japan stepped up and brought the negotiations to a successful conclusion in the renamed Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). It was through Tokyo’s renewed efforts that the CPTPP made it through negotiations in the absence of the United States. This development demonstrates a shift in agency on the Japanese side: from a supporter of the agreement to an architect and champion of this important part of the rules-based order.

Finally, Japan has become a more forceful and confident actor in its own right. One need only look at its multiple references to China in statements with the United States at the recent 2+2 Meeting or Japan’s Minister of Defence Kishi Nobuo’s address during the 2021 Ottawa Conference on Defence and Security. Japan held a 2+2 meeting with Germany and was aiming to line up visits with India and the Philippines before both were cancelled due to the COVID-19 situation in these two countries. The cooperation with Manila is right on the heels of actions by Chinese fishing boats, possibly affiliated with China’s maritime militia, encroaching into the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

We are seeing the rebirth of a more capable, and clear-eyed Japan, and like-minded states are beginning to take note of this development and are eager to develop more fruitful and expansive ties. Such states should recognize that Japan’s situation is frequently an early reflection of what will then occur to others, just as Tokyo has recognized the plight of others, and acted accordingly. The upcoming port visit and planned exercises by the UK’s HMS Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by ships from the Netherlands and the United States, as well as Germany pledging to send a ship of its own, can be seen in this regard.

Japan is no longer merely an economic and trading partner, but is increasingly viewed as a valuable strategic partner. It was under former Prime Minister Abe (2006-2007, 2012-2020) that many of these changes were ushered in, such as efforts to change the constitution to legalize the Self-Defense Forces, the formation of a National Security Council (with roots in the mid-2000s, during Abe’s first Premiership) and National Security Strategy and the changes to legislature needed to allow for collective self-defence.

Yet this momentum did not end with Prime Minister Abe. Since Abe’s sudden resignation, Japan has begun to stake even more conspicuous stances, such as ties with Taiwan. Tokyo has also recently made similarly pointed statements in concert with Indonesia. Frequent incursions into Japanese waters around the Senkakus will only harden its resolve and accelerate its measures. Indeed, there are signals that Japan might do away with its 1% GDP cap on defence spending. As Japanese Defence Minister Nobuo Kishi has made clear, “We must increase our defense capabilities at a radically different pace than in the past.”

For all intents and purposes, the changes that former Prime Minister Abe ushered in represent a broader shift in Japanese policy-making.

All of these reasons are related to a new development: uncertainty around America’s involvement in the region. Simply put, US allies in the region, not least Japan, have become more doubtful about the stability of continued American support. While precipitated by the Trump administration’s self-interested behaviour, the damage may prove more long lasting. Certainly, while the new Biden administration is saying all the right things, particularly in regards to the Senkakus, Tokyo has been forced to consider a more robust, active, and visible foreign policy outlook, while still embracing cooperation with the United States. Interestingly, uncertainty over US support may have prompted Tokyo to “diversify” partners and take on a greater leadership role, which explains its closer dialogue efforts with actors in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.

For several decades, Japan has quietly been supporting the world’s rules-based order, in concert with others. Now, we see a Japan that is more willing and able to guide and shape this order in concert with allies and partners. It is one of the few truly reliable democracies in the region, and almost certainly the most committed to a rules-based order, with the capabilities and ambition to match. In short, far from being a vassal for the United States in the region, Japan has emerged as a leader in the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific – and we are only at the beginning of this new shift. Expect even bigger things from Japan in the future.

Matthew Neapole holds an MA in International Relations from the University of Groningen and is particularly drawn to the dynamic Indo-Pacific, the evolving Japanese security situation, as well as China’s strategic policy. He lived for nearly a decade in Japan, as well as in the Netherlands and Belgium.