Stronger ties with Canada will not replace Japan’s alliance with the US— but it will play a complementary role that will pay dividends in the years ahead, writes J. Berkshire Miller.

Stronger ties with Canada will not replace Japan’s alliance with the US— but it will play a complementary role that will pay dividends in the years ahead, writes J. Berkshire Miller.

By J. Berkshire Miller, July 10, 2019

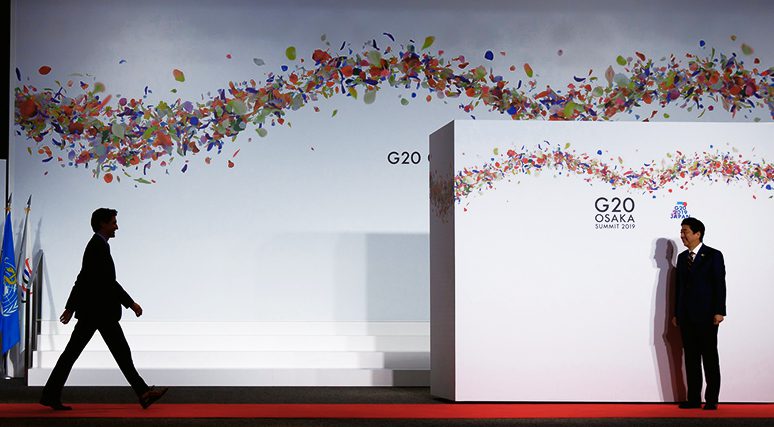

Last month, on the eve of the G20 summit in Osaka, reports emerged that U.S. President Donald Trump was openly mulling a withdrawal from the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty as a result of an “unfair” sharing of alliance burdens.

The reality is that there has been no change to the strength of the U.S.-Japan alliance, and both sides were quick to dismiss any uncertainty.

But the remarks, which fall in line with Trump’s standard “America First” rhetoric, underscore once again why Tokyo needs to continue building partnerships with other like-minded countries invested in a secure and rules-based Indo-Pacific region. This is not to replace or hedge against the U.S. alliance, but rather to complement and diversify the stakeholders supporting a free and open Indo-Pacific.

These developments have been happening already to some extent as Japan develops stronger security partnerships with Australia, India, the U.K., France and also countries in Southeast Asia.

One security relationship that has been traditionally slow to progress, but has great potential and increased momentum, is that of Canada and Japan.

Following the Shangri-La Dialogue — Asia’s premier security forum — Iwaya last month hosted Canadian Defense Minister Harjit Sajjan for a bilateral visit in Tokyo. During Sajjan’s visit, Canada and Japan agreed to work to advance a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific,” a strategy promoted by Tokyo for a more stable and prosperous region spanning from East Africa to the Eastern Pacific.

During the visit, Japan and Canada underscored the importance of an agreement to strengthen military-to-military cooperation between the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and the Self-Defense Forces signed last year. Known as the Acquisition of Cross Servicing Agreement (ACSA), the arrangement will allow both countries to make efficient use of each other’s military equipment during operations and exercises in Canada, Japan and other locations. The agreement will also advance bilateral cooperation in response to humanitarian and disaster crises, peacekeeping initiatives, and allow greater collaboration with third partners, including the United States.

In addition to the ACSA agreement, both sides are moving towards greater interoperability between their militaries with a growth in joint exercises and high-level exchanges. In 2017, the two sides commenced bilateral naval drills dubbed “Kaedex” (kaede is maple leaf in Japanese) and the Canadian Navy also participated last year in the U.S.-Japan “Keen Sword” exercises.

Canada has also been working with Japan, and other allies in the Five Eyes intelligence network, to help monitor and disrupt attempts by North Korea to evade sanctions over its nuclear and missiles programs — through surveillance of ship-to-ship transfers in the East China Sea.

What are the drivers pushing forward this improved relationship?

Traditionally, trade and investment have been the key engine of engagement between Japan and Canada. While this has served the relationship well over the years, it is time for both sides to adapt to their ties and look at more cooperation on regional security and defense relations.

On one hand, Japan is courting enhanced relationships with foreign partners through its “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” vision. Canada, meanwhile, also is looking to reorient its defense posture to be more active in the Indo-Pacific and Japan should be the logical cornerstone of such efforts.

The defense ministers dialogue may not appear consequential at first glance, but closer inspection shows that it is the latest in a trend of blossoming security ties between Tokyo and Ottawa.

Canada and Japan also are the two largest economies in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) — or TPP 11 — ratified earlier this year.

Under the pact, Canada has preferential access to the Japanese market and — perhaps more importantly — has worked with other partners to set a high-bar on the standards for progressive and high-ambition trade agreements.

But there are more steps to take in this nascent security relationship.

This past April, during Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Ottawa, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made the first high-level Canadian endorsement of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” — a vision that is also shared by other like-minded states, such as the U.S. and Australia.

This vision fundamentally rests on the maintenance of a rules-based international order premised on common norms, laws and practices, with an aim at reducing the potential for conflict and promoting sustainable development.

This of course draws a stark contrast to China’s increasingly aggressive posture in the region, marked by its militarization of man-made islands in the South China Sea and its controversial lending practices through its “Belt and Road” initiative.

For another, Beijing’s coercive attempts have increasingly drawn Ottawa’s concerns — issues ranging from the arbitrary detention of two Canadian citizens to the sealing off of much of the market for Canadian exporters of canola, soybeans and meat — to force Canada to relent on the sensitive extradition case of Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou.

To be sure, Tokyo, in contrast with Washington and Ottawa, is enjoying warmer relations with Beijing after years of abysmal ties over historical and territorial issues. Chinese leader Xi Jinping made his first visit to Japan as president last month at the Osaka G20 summit, and there are plans for him to visit as a state guest next year.

But Tokyo knows that the warming of relations with its neighbor is a tenuous one that can turn sour depending on the political winds in Beijing — and the Abe administration is fully aware that it needs to prepare for rainy days ahead.

Stronger ties with Canada will not replace Tokyo’s alliance with Washington — but it will play a complementary role that will pay dividends in the years ahead as Japan increases its geopolitical importance in the face of China’s rising dominance.

J. Berkshire Miller is deputy director and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He is also a senior fellow at the Japan Institute of International Affairs, the Asian Forum Japan (AFJ) and a distinguished fellow at the Asia-Pacific Foundation of Canada.