June 1, 2012 – In his latest column for iPolitics, MLI’s Jason Clemens makes sense of the U.S. economy and Obama’s chance at re-election. The full column is below.

Making sense of the U.S. economy

By Jason Clemens, iPolitics, June 1, 2012

There is little doubt that the economy, and job creation in particular, will be the dominant issues of the coming U.S. presidential election. While the economy shows some tepid signs of recovery, there is much confusion about both the state of the economy and the degree to which President Obama should be held accountable. Making sense of both issues will be instrumental in determining whether President Obama is re-elected.

The U.S. economy officially emerged from recession in 2009 but economic growth has been anemic. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, which tracks economic performance, the current recovery is the weakest of the eleven tracked since World War II. Specifically, the bank calculated that cumulative economic growth in the U.S. since emerging from the recession has been 6.8 per cent. Since World War II the average cumulative growth over the same number of months during recovery from recession has been 15.2 per cent.

But the unemployment rate is declining so things must be getting better. Actually no. The labour market is one of the more ominous indicators of the U.S. economy. While the unemployment rate has declined from its peak of 10.0 per cent in late 2009 to its current level of 8.1 per cent, much of the decline is due to people becoming so discouraged with their prospects that they drop out of the labour market.

For example, the unemployment rate in April dropped by 0.1 percentage points. However, the decline wasn’t due to the addition of roughly 115,000 jobs, which was the slowest increase in six months. Rather, the decline in the unemployment rate was due to the fact that some 350,000 workers stopped looking for employment. Indeed, the labour participation rate in the U.S. is now at its lowest level since the early 1980s.

Some of this poor economic performance can be attributed to the nature of the recession. Economic recoveries after financial crises tend to be slower than recoveries from non-financial recessions. This is aptly documented by Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff in This Time is Different, which chronicles 800 years of financial upheaval. One of their many insights is that recoveries from financial crises tend to be slower. President Obama cannot reasonably be held accountable for a financial crisis that pre-dates his election.

However, many of the policies pursued and often implemented by the Obama Administration have had a demonstrably negative impact on the economy and job creation. For this he can certainly be held to account. Rather than detail specific problems in policy areas such as taxes, deficits, debt, health care, and financial regulation, it is worthwhile to examine one common trait – uncertainty – that runs through much of the legislation implemented by the administration in conjunction with the previous Democratic Congress.

Uncertainty is a killer for an economy. It makes economic calculations by businesses, investors, entrepreneurs, and families much more difficult, indeed almost impossible in many circumstances. It’s still unclear, for example, what the requirements will be for businesses to provide health care to their employees under Obamacare. Add to this the legal uncertainty of Obamacare given the multiple lawsuits contesting its constitutionality. If you’re a business owner contemplating expanding, you simply do not know what health care costs (or associated taxes and fees) may be imposed on you in the future. The response, not surprisingly is that businesses hold off expanding and investing, curtailing job creation that might have otherwise occurred.

Similar ambiguity and uncertainty exists in tax policies and the Dodd-Frank financial services regulations, to name just two. There are a host of taxes expiring at the end of 2012, which currently means a rather marked increase in income, payroll, and investment-related taxes. The President and Congress have been waffling and debating what to do. In the interim, people simply cannot estimate with any reasonable degree of certainty what their tax liabilities will be come January 2013. The response is again to stay on the sidelines.

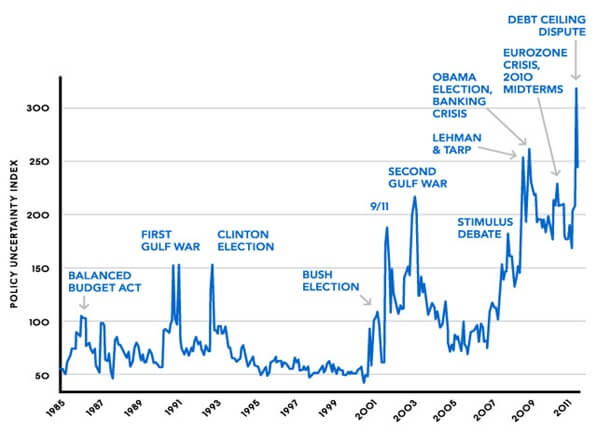

Linking uncertainty with poor economic performance is not just conceptual or theoretical. Economics professor Scott Baker along with his colleagues have actually measured policy-based uncertainty and linked it empirically with poorer economic outcomes. According to their analysis, policy-based uncertainty reached “extremely high levels” during the past several years and especially during events like the stimulus debate (2009), the Lehman bankruptcy and TARP legislation (2008 and 09), and the U.S. debt ceiling negotiations and Eurozone crisis (2011). This policy-driven uncertainty post-recession is one of the explanations for the comparatively sluggish U.S. recovery.

The President and Congress have an opportunity to improve the economy by reducing policy-based uncertainty through reasoned compromise. Unfortunately, the advent of the general election will more than likely prevent any such accommodations, which both the President and the Congress should be held accountable.

Jason Clemens is the Director of Research and Managing Editor at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Policy Uncertainty Index