Looking for ways that robots and humans can effectively co-exist and work is a discussion worth having, writes Linda Nazareth.

Looking for ways that robots and humans can effectively co-exist and work is a discussion worth having, writes Linda Nazareth.

By Linda Nazareth, December 5, 2018

It really was not as simple as a bunch of robots swooping in and telling the auto workers that they were done and that the cars were going to be made a different way. General Motors’ decision to close plants in Oshawa, Ont., as well as four others in the United States, was all about costs and restructuring and probably some politics as well. Yet at the end of the day, technology played a strong part in the decision and will continue to affect what happens next in autos and everywhere else. Accepting that, the next question becomes whether we should change policies so as to deal with these new realities.

Along with the rest of the auto sector, GM is in transition. The future is about electric cars rather than gas-powered ones and about SUVs rather than sedans. The manufacturing processes for the new products are different than those for the old, and so are the skill sets required. Lost in the headlines about layoffs at GM was the fact that the company this year has been aggressively hiring engineers, bringing on-board hundreds at their technology campuses in Ontario, as well as committing $1.8-million to encourage would-be students to study STEM programs (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) through a series of scholarships in the province.

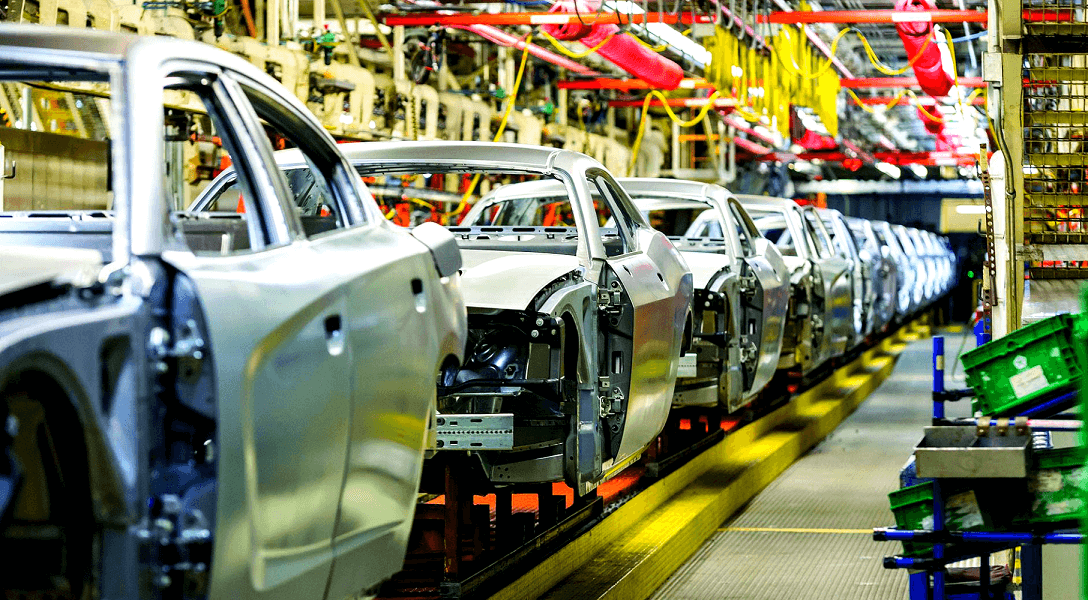

Robots, and automation in general, have been part of the ongoing transition within the auto industry. According to the International Federation of Robotics, auto companies have been forerunners in the charge to deploy robots in production. GM has been particularly aggressive in their adoption. The company is actually a leader in “cobots” or collaborative robots, clever machines that are open-minded enough to work alongside human beings on production lines. In their Shanghai plant, the cobots are a key component of a plan to eventually build electric vehicles for the Chinese market.

All of this is great for efficiency and productivity, and ultimately that tends to drive profitability. Without that profitability, job prospects are pretty dim for human beings. That said, there is no denying that in the short term there are going to be disruptions to employment as companies such as GM reassess and restructure their processes.

So is it time for a robot tax? That’s an idea that has been bandied around by the likes of Bill Gates, one of the Silicon Valley giants who has changed the world through technology and who now seems a little horrified by what he has helped unleash. Mr. Gates realizes well that the future will be one that requires fewer workers who do not have specialized or advanced skills. As a way for governments to raise money to help those workers, he suggests that a robot tax be implemented on companies that move to greater automation.

Put very simply, a robot tax would basically be a subsidy to encourage hiring a human rather than buy a machine. Things such as payroll taxes are effectively levies on labour after all, so a robot tax would even that playing field a bit and presumably make the robot relatively less attractive. Not that Mr. Gates or anyone arguing for the tax is naive enough to think that it would actually prevent any company from moving to robotics if that worked for them. It would just force them to pay a little extra for doing so, which would raise some money to aid displaced workers.

And for sure, we are going to be talking a lot more about robots and cobots and displaced workers in the future, and maybe in the near future. According to a report by consulting company Oliver Wyman, countries that have the lethal combination of a high concentration of aging populations and older workers in the manufacturing sector are the most vulnerable to job losses as a result of automation, which is why China and Vietnam top its list of those who will see the most disruption. The United States is in 10th place and Canada is way down at 14, no doubt because our economies are less manufacturing dependent than they used to be. That makes the economy as a whole less vulnerable to automation disruptions, but does not protect individual sectors or companies.

Of course, at the end of the day, a robot tax is just one more tax on business – a tactic that never really does much to create employment. Any country that pushes to adopt such a tax could reasonably be expected to see fewer – not more – jobs come into play. Still, looking for ways that robots and humans can effectively co-exist and work is a discussion worth having at a time when the former seems to be getting an edge on the latter.

Linda Nazareth is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Her book Work Is Not a Place: Our Lives and Our Organizations in the Post Jobs Economy will be published this month.