This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, July 14, 2025

At the NATO summit in late June, Prime Minister Mark Carney was asked how Canada plans to fund the alliance’s ambitious new target for military spending: 5 percent of GDP. Would it mean higher deficits, new taxes, or cuts elsewhere? And how much debt is the federal government willing to tolerate?

The prime minister’s answer—faster growth and a balanced operating budget within three years—sidestepped the real issue. Namely, that meeting this defence commitment will require one of three hard choices: larger deficits, higher taxes, or significant spending cuts. It could even involve all three.

Little wonder there are now reports that the federal government is looking to lower program spending by 15 percent by 2028. But by the mid-2030s, even this may not be enough.

Short-term challenges

A recent analysis by the C.D. Howe Institute paints a sobering picture. Accounting for recent policy decisions—including the cancellation of the capital gains tax, the reduction in the first income tax bracket to 14 percent, the removal of the GST for first-time homebuyers, the shelving of the digital services tax, and a range of platform commitments—the deficit for this fiscal year could exceed $92 billion. Next year, it may approach $82 billion. These levels, if sustained, would push the net-debt-to-GDP ratio from its current level of roughly 43 percent to over 44 percent by 2028.

While these figures are not yet alarming in an international context, the longer-term trajectory is troubling. With new spending accelerating and revenues constrained by tax cuts, the fiscal landscape through 2035 is far more challenging than it appears today.

Military spending boost could double the deficit by 2035

Building on the C.D. Howe projections, I constructed my own forecast for federal finances to 2035. Nothing too sophisticated, but entirely reasonable to provide a good sense of scale.

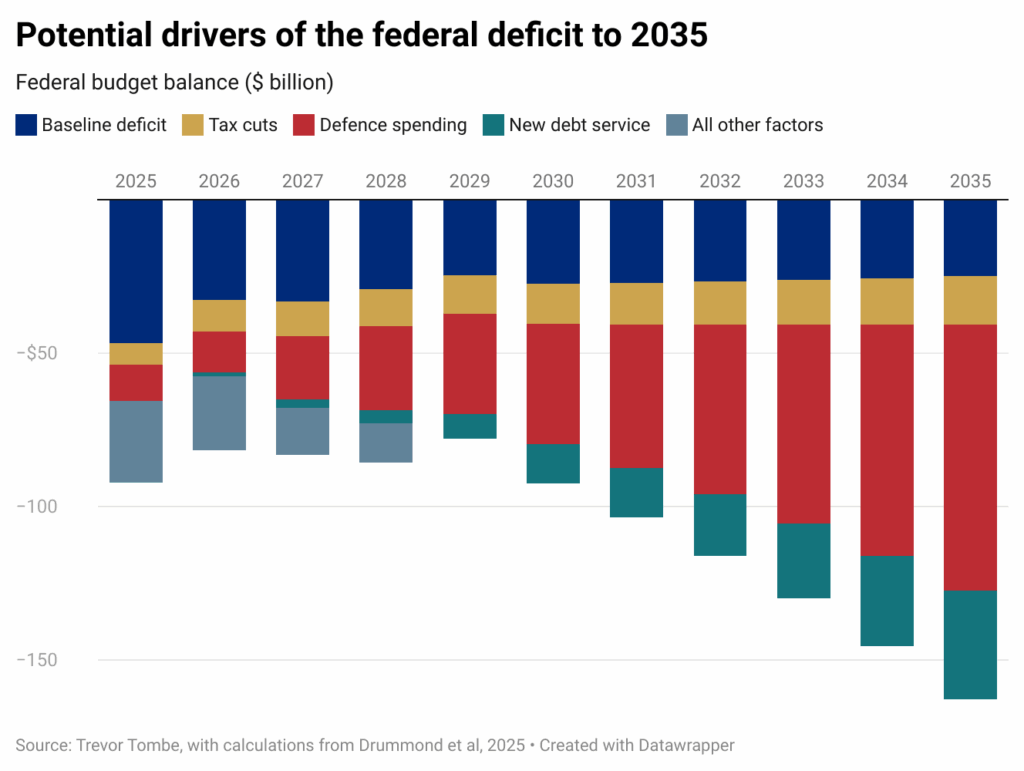

Under conservative assumptions—where current tax cuts remain in place, new platform commitments are phased out after 2028, defence spending ramps up to 5 percent of GDP, and baseline revenue and program spending grows with the economy—the deficit would decline modestly to $78 billion by 2029, but then resume its upward climb. By 2035, I estimate the increase in military spending alone would add approximately $87 billion to the baseline deficit.

Combined with a $15 billion revenue hit from tax cuts, and substantially higher debt service costs that add roughly $35 billion more to total spending, this turns a baseline $25 billion deficit into one exceeding $160 billion by 2035. Total federal debt in this scenario could potentially rise to well over 50 percent of GDP by that year.

One could, of course, quibble with some of the underlying assumptions here. But if this is even close to reasonable, then it is completely unsustainable.

More than an operating budget problem

The government’s emphasis on balancing the operating budget, however welcome this may be on its own, is insufficient.

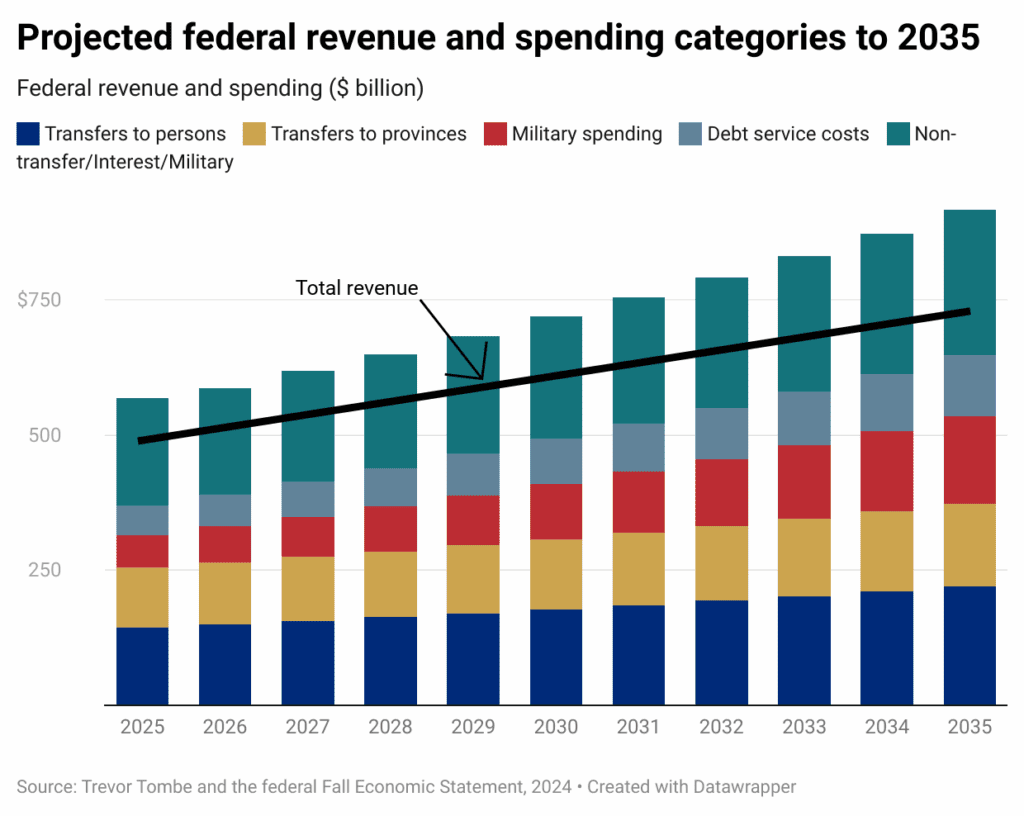

To appreciate the scale of the challenge, it’s important to understand the structure of the federal budget. Transfers to individuals, especially seniors, make up the largest share of federal spending—$85 billion today, projected to surpass $104 billion by 2029. With other transfers, such as the Canada Child Benefit and employment insurance, included, this total is expected to exceed $170 billion by the end of the decade, and I project it will reach roughly $220 billion by 2035. Transfers to provinces, meanwhile, could top $150 billion by then. And defence spending alone could reach even more than that.

If spending less in these areas is off the table (as political leaders of all political stripes consistently say), there’s not a lot left.

If transfers to people and provinces, interest payments, and military spending are all left untouched, then balancing the budget by 2029 would require eliminating roughly 40 percent of all remaining federal program spending. By 2035, that burden would increase to between 50 and 60 percent—depending on how large the prior year deficits are—which is equivalent to between $130 and $160 billion in savings that year.

Looking for spending cuts only within the roughly one-third of the budget accounted for by non-interest, non-military, and non-transfer spending results in a scale of reduction that, I think it’s safe to say, is not realistic.

Raising revenue or reforming transfers

This brings us to the inevitable conclusion: new revenues or shrinking the growth in transfers to both people and provinces should probably be on the table.

Indeed, some analysts are already (and not surprisingly) calling for increases to the GST or other taxes as a way to bridge the fiscal gap.

If the government rules that out, then cuts in transfers to individuals and provinces—especially to seniors—are the only things left. This could mean raising the eligibility age for Old Age Security, tightening income thresholds, adjusting benefit phase-outs, or fundamentally redesigning how provincial transfers grow over time.

What about higher rates of economic growth? Faster GDP growth means more income for households and profits for businesses, resulting in higher federal revenues. This indeed would shrink the projected baseline deficit. But since military spending goals are themselves a function of the size of the economy, 5 percent of a now larger GDP would necessitate even more military spending. Other areas of federal spending also grow with the economy, including major transfers like the Canada Health Transfer and Equalization.

We can’t grow our way out of these particular fiscal challenges. (Although, of course, a stronger economy would be welcome for any number of other reasons!)

The real debate ahead

Whatever one thinks about whether Canada’s pledge to spend 5 percent of GDP on defence is a worthwhile goal or not, we’ve committed to it. Following through on that will carry a steep fiscal cost that cannot be ignored. It will require either sustained deficits, tax increases, or difficult reductions in other areas of federal spending. It is likely that it will take a combination of all three at a scale far beyond what many Canadians realize.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum.