This article is the first of four articles in a Macdonald-Laurier Institute special series: Delivering Basics – The ongoing Indigenous water crisis in Canada.

By Matthew Cameron and Ken Coates

November 28, 2023

Most Canadians take safe, clean drinking water for granted. Most, but not all. Instead, those Canadians, predominately Indigenous citizens, subject to drinking water advisories – including the more than 17,600 across Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario subject to such advisories for at least a year – take for granted that they need bottled water to drink, cook and carry out other daily tasks like brushing their teeth and bathing.

How is it that so many citizens of Canada, a developed, first-world country that boasts a modern democratic society and takes immense pride in its public health care system, go without access to clean drinking water? Indeed, three separate Ontario communities, home to a total of over 3,000 residents, have had drinking water advisories in place for more than 20 years. Despite touting one of the world’s most advanced economies, and proclaiming itself a leader on the international stage through its engagement with organizations like the United Nations and the G7, why has Canada been unable to provide basic necessities like clean drinking water to its citizens for over two decades?

While access to clean drinking water is a basic necessity, an established human right, and arguably a constitutional right in Canada, providing it to each of the roughly 40 million citizens of the world’s second-largest country by area has proven to be surprisingly complex. Without a doubt, politics, money and racism have all been contributing factors, as in the case of so many other social issues in Canada and elsewhere in the world. Despite the temptation to identify an easy scapegoat, however, it is not simply a lack of political will that has prolonged drinking water advisories in Canada.

Over the past several decades, successive federal governments have recognized and acknowledged the problem, pledged to tackle it, and committed substantial financial and legislative resources to address the issue. And yet, successive governments have failed to eradicate drinking water advisories, with at least 27 Indigenous communities across the country currently impacted. A closer look reveals that notwithstanding political efforts, a variety of policy decisions refracted through multiple levels of government, as well as geographical, logistical and informational challenges have contributed significantly to making access to clean drinking water one of the most persistent and troubling problems in Canada, particularly in First Nations communities.

Drinking water advisories are an important precautionary measure to protect public health. Advisories can be issued by a local government, First Nation or public health authority when drinking water quality has been or may have been compromised to the point where its consumption poses a risk to human health. Water quality can be adversely impacted as a result of any number of factors, including a deterioration in source water quality (e.g., contaminated groundwater or aquifers supplying wells); the presence of bacteria such as E. coli; unacceptable concentrations of chemicals or particles; problems associated with water treatment and distribution; or for failing to meet the Canadian Drinking Water Guidelines.

Advisories may advise consumers to boil water before drinking it, advise against the consumption of water, or advise against any use of water available through a public water system (e.g., bathing, washing clothes). Ideally, such advisories are temporary measures that allow compromised water systems to be fixed and put back into operation. In reality, however, some advisories remain in place for prolonged periods of time. Drinking water advisories that have been in place for more than 12 consecutive months are known as long-term drinking water advisories.

Based on advice from an environmental health officer, the chief and council of impacted First Nations are responsible for issuing water advisories. Likewise, once corrective measures have been taken to ensure drinking water is safe for consumption, an environmental public health officer wi ll ad vise th at an advisory can be lifted. At this point, it is up to the chief and council to lift the advisory.

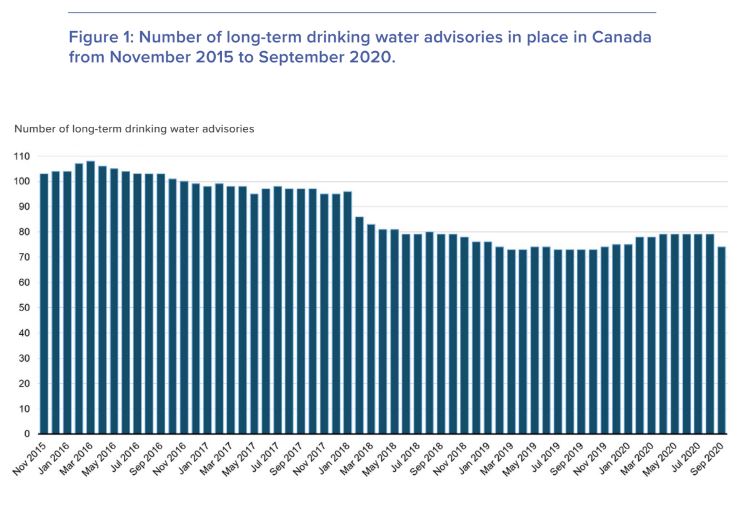

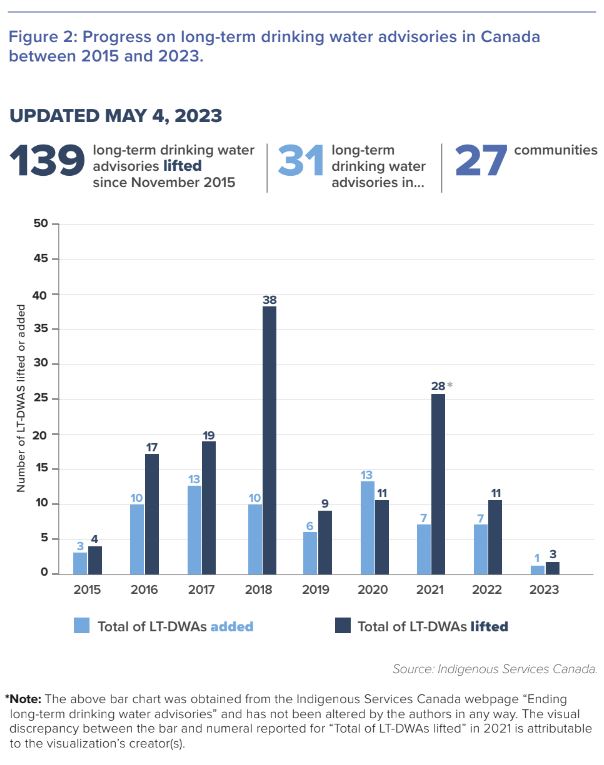

As of May 2023, there were a total of 31 long-term drinking water advisories in effect in Canada, impacting 27 Indigenous communities. According to the Government of Canada, since 2015, a total of 139 long-term drinking water advisories have been lifted, reflecting improvements in 90 Indigenous communities. As a result of collaboration between the federal government and impacted First Nations to address water quality issues, there was a relatively stable decline in the number of long-term drinking water advisories in place in Canada between 2015 and 2020 from 105 to 58 (see figure 1), and that trend has continued over the past three years (see figure 2).

Of the 139 long-term drinking water advisories lifted since 2015, 23 were in place for over five years, 34 were in place for over 10 years, 15 were in place for over 15 years, and seven were in place for over 20 years. Of the 31 still in effect in May 2023, three have been in place for over five years, over 10 years, over 15 years, and over 20 years, respectively – leaving 19 that have come into effect within the past 5 years.

At first glance, the numbers from 2015 to 2023 seem to indicate genuine progress towards increasing access to clean water in Indigenous communities. Indeed, in many cases there has been encouraging progress. For example, after nearly 25 years of drinking water advisories, the Shoal Lake 40 First Nation officially opened a new centralized water treatment plant in 2021 and lifted the community’s drinking water advisory. The water treatment plant cost more than $30 million to build and was made possible after an all-season road provided year-round access to the remote community, allowing materials and equipment to reach the community. Today, nearly 300 residents, including children and young adults who had lived their entire lives under drinking water advisories, have safe, clean and reliable drinking water flowing into their homes.

But the numbers don’t tell the whole story; in fact, far from it. They can be misleading, incomplete and, if anything, are at best a rather coarse-grained indication of the scope of the problem. For instance, five of the 90 First Nations communities in which long-term drinking water advisories have been lifted since 2015 have had new long-term drinking water advisories issued since 2019. Two of those communities had each had their previous long-term drinking water advisories in place for over 15 years.

Moreover, the numbers reported above pertain exclusively to those public water systems that the federal government has funded since 2015. An additional 12 long-term drinking water advisories are in effect in First Nations communities in Saskatchewan, Ontario and New Brunswick for water systems that are not financially supported by the federal government. There are also 10 long-term drinking water advisories in British Columbia, including in communities that are counted by the federal government amongst those that have had advisories

lifted since 2015.

And that’s just the communities south of the 60th parallel. The Northwest Territories and Nunavut each have one long-term drinking water advisory in effect, bringing the current total across Canada to at least 55. The lack of clear, consistent, and transparent data collection regarding long-term drinking water advisories makes it difficult to get a clear picture of the full extent of the problem within Canada.

Further, the raw numbers of advisories issued and lifted over time do not directly reflect overall progress on addressing the issue. While it is tempting to view an increase in the number of advisories lifted and a decrease in the “total” number of advisories in place as signs of increased traction in the effort to eradicate long-term advisories altogether, this is not necessarily the case. As noted above, a given community can have a long-term advisory lifted only to have another one issued within a few years, indicating a persistent problem that is not being fully resolved. Moreover, the numbers themselves can also more generally reflect the type of approach being taken to address the issue at a given time.

In 2009, Health Canadapublished a report entitled, Drinking Water Advisories in First Nations Communities in Canada: A National Overview 1995-2007. It found “the existence of a significant increasing trend in the number of [drinking water advisories] in effect between the periods of 2003 and 2007”(14). Indeed, during that timeframe, the number of long-term drinking water advisories nearly doubled from 58 in 2003 to 104 in 2007. The report also found that “[t]he number of First Nations communities affected by [drinking water advisories] also follows a significant upward trend during the same period”(14).

One could easily mistake this as an indication that the state of First Nations water systems was in a period of serious decline from 2003-2007. In fact, 2003 was the year that the federal government implemented the First Nations Water Management Strategy, which led, among other things, to increased testing, reporting, training and capacity to address water quality issues. The report notes that “the number of water samples tested increased seven fold [sic] from 2002 to 2006”(19) and that “reporting of [drinking water advisories] data to Health Canada Headquarters was more consistent after 2003”(4). During that time, “the number of First Nations communities with access to Community-Based Water Monitors and the number of communities with access to portable kits for biological analysis has more than doubled while the number of Environmental Health Officers has increased by one third”(19).

Far from indicating a problem getting worse, the increased numbers of drinking water advisories from 2003-2007 reflected a more accurate representation of the problem itself and allowed for a much better understanding of its scope than existed previously; thanks to more focused attention on the problem coupled with increased resources and improved coordination to address it. In this case, increased numbers of long-term drinking water advisories plausibly indicate progress in addressing the problem. As the report notes, “[w]hen water-quality monitoring and reporting is increased, it is more likely that problems will be detected, which in turn increases the number of [drinking water advisories] issued”(19). In this sense, the First Nations Water Management Strategy was successful in scoping out the problem and increasing the capacity among First Nations and the federal government to address it through “improved staffing and increased water sample testing that allow timely and informed decisions for the protection of public health”(23).

In short, the numbers themselves are a rather poor indication of the scope of the problem and they risk oversimplifying the issue given the different reasons why an advisory might be in effect and the different factors involved in lifting an advisory that has been issued. Increased awareness, improved testing, enhanced monitoring, better coordination, and information sharing are all factors that will help to address the scourge of long-term drinking water advisories in Canada – in addition to the appropriate infrastructure to properly treat and distribute water to citizens. These in turn require dedicated resources, community involvement, cross-jurisdictional collaboration, and sustained engagement with the issue.

About the authors

Matthew Cameron is a Yukon-based researcher and academic. He is an Instructor at Yukon University, where he has taught in the Liberal Arts, Indigenous Governance and Multimedia and Communications programs since 2016.

Ken Coates is a Distinguished Fellow and Director of Indigenous Affairs at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a Professor of Indigenous Governance at Yukon University. He was formerly the Canada Research Chair in Regional Innovation in the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Saskatchewan. He has served at universities across Canada and at the University of Waikato (New Zealand), an institution known internationally for its work on Indigenous affairs.