OTTAWA, ON (April 18, 2019): Canada has been experiencing surprising growth in employment despite a consistently-sluggish economy. And, even though job numbers are looking good, wage growth remains stagnant. What explains these contradictions?

OTTAWA, ON (April 18, 2019): Canada has been experiencing surprising growth in employment despite a consistently-sluggish economy. And, even though job numbers are looking good, wage growth remains stagnant. What explains these contradictions?

To make sense of all this “noise,” the Macdonald-Laurier Institute has released its Labour Market Report for Q1, 2019. Report author and MLI Munk Senior Fellow Philip Cross says that to understand what’s going on, it important to look at what has changed in Canada over the last few months and how those changes have impacted the private sector.

“There are a number of possible explanations for why job growth has recently exceeded GDP,” writes Cross, arguing that the most convincing explanation is that “firms in Ontario delayed hiring employees in the first half of 2018 until they were certain that the Wynne government would not be re-elected.”

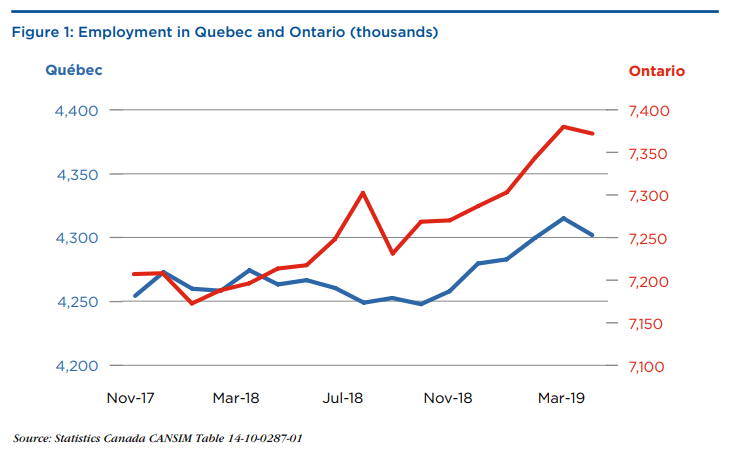

“Since the Progressive Conservatives took power, Ontario has driven job growth in Canada, with employment gains accelerating to 0.3 percent in the fourth quarter and 1.1 percent in the first quarter (see Figure 1). By itself, employment in Ontario accounted for 60 percent of Canada’s surprising first-quarter burst in jobs.”

According to Cross, the same story is true of Quebec, where employment rebounded following the election of a more business-friendly government. The stark and observable pattern of employment growth contrasts most strongly against Alberta, which has seen painfully slow employment growth.

“While it has yet to be seen whether the new Alberta government will be able to encourage the sort of business confidence that has led to hiring sprees in central Canada, it is clear that employers have been responding positively to governments that have not increased their labour bills.”

That said, despite high overall employment in Canada, stagnant labour productivity has become chronic in Canada. Cross argues that the stall in productivity is “symptomatic of the declining competitiveness regularly cited by Canada’s business leaders.” Business investment is 10 percent below its 2014 peak, and exports have remained troublingly weak, perhaps due to a lack of investor confidence in the global economy and Canada’s business climate.

And, although high-employment tends to result in better overall income growth, Canada has been experiencing a virtual absence of real wage growth between 2014 and 2018.

“While employment growth has been slightly higher under the current government than the previous government, the same cannot be said of average incomes overall,” Cross explains. “During the Harper years, real income grew by an average annual gain of 3.0 percent. By contrast, the Trudeau government has seen by a slower average of just 1.7 percent per year.”

While there could be any number of reasons for this discrepancy, these trends will nonetheless become increasingly scrutinized in the weeks and months leading up to October’s Federal Election. If it persists, the slower wage growth could be a thorn in the government’s side, particularly given the Liberal’s 2015 pledge to focus on improving outcomes for middle-class Canadians. Read the MLI Labour Market Report for Q1, 2019 to find out more.

For more information media are invited to contact:

Brett Byers-Lane

Communications and Digital Media Manager

613-482-8327 x105

brett.byers-lane@macdonaldlaurier.ca