By David Zitner

By David Zitner

September 29, 2022

Despite the absence of supportive evidence, the American Academy of Pediatrics recently suggested that aggressive and clearly harmful medical and surgical interventions might be appropriate for many children who express reservations about their biological sex (Szilagyi 2022; Rafferty et al. 2018).

At the same time, other experts on transgender medicine, including some who are themselves transgender, are raising serious doubts about the quality and value, for young people, of “gender affirming care” (Ault 2021). They are clear that, for youth, the unavoidable short-term harms outweigh the theoretical long-term benefits.

“The latest skirmish was set off by comments made by Marci Bowers, MD, president-elect of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and Erica Anderson, PhD, president of the U.S. Professional Association for Transgender Health” (Ault 2021).

Dr. Bowers is a skilled gynecologist, who is herself transgender, and performs gender affirming surgery on adults as well as clitoral restoration surgery for adult woman who have suffered genital mutilation (Clitoris.io Undated). Clearly Dr. Bowers does not have a general aversion to major surgery for determined and consenting adults.

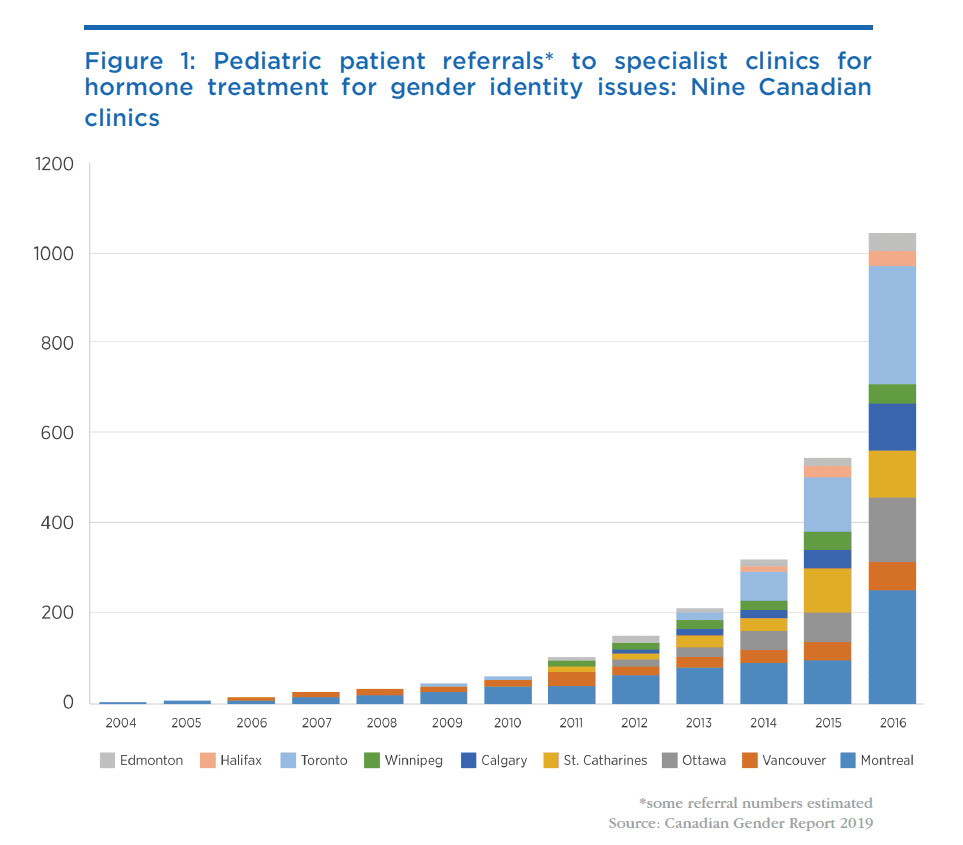

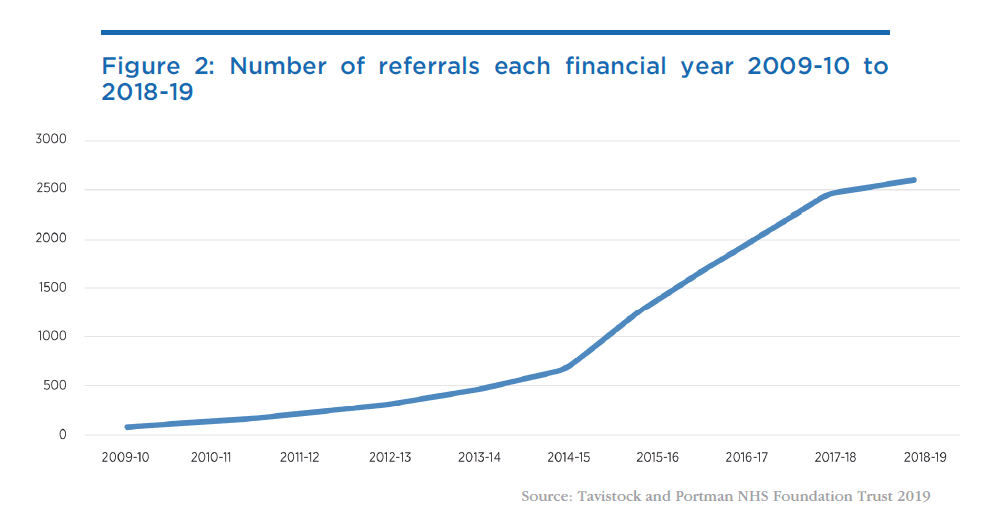

However, Dr. Bowers and transgender psychologist Erica Anderson are distressed and sound an important alarm. They are concerned that children are, on the basis of little or no clinically-proven evidence, being subjected to immediately harmful, complicated, and often irreversible medical and surgical interventions. They note the increasing incidence of, often temporary, rapid onset gender dysphoria (ROGD) where youngsters express an interest in changing from their birth sex, an interest that diminishes or disappears as they get older. Bowers and Anderson emphasize that many people change their minds! And yet at exactly the same time that these alarm bells are being rung, the number of young people now receiving gender affirming care leading to transition is skyrocketing. Figure 1 shows Canadian data and Figure 2 shows data from the UK. Trends are similar in the US (Vesterberg 2022).

Sex reassignment from male to female or female to male is not a benign medical procedure. Hormones and puberty blockers influence growth and development, and trans people are subject to increased risk of various illnesses. A recent Macdonald-Laurier Institute paper (Pike, Hilton and Howe 2021) contains an excellent discussion of the known short- and long-term harms of medical procedures aimed at gender reassignment.

Unfortunately, these aggressive interventions are not based on scientific studies demonstrating overall long-term benefit, nor studies showing which children are most likely to achieve benefit or harm, nor any studies assessing how many young people suffering from ROGD later change their minds and embrace their birth sex. Missing too is information about the proportion of people of various ages who have had gender reassignment procedures who subsequently regret having had those procedures.

Indeed, it seems that mental health issues, and particularly depression, are worse among trans adults (Kattari et al. 2020) than among the general population. There are allegations and opinion, but not sound evidence, that mental health improves after transition surgery (Ring and Malone 2020). We do not know if these mental health disturbances arise because of how trans people are treated by families, physicians, and communities or whether they indicate abnormal biology.

In the absence of the sort of evidence listed above, how can adults, parents, and children decide what to do in the face of conflicting advice from credentialed advisors? And given the politicization of these issues, not least by so-called “conversion therapy” bans, many medical professionals are reluctant to inform young patients fully of risks, or to suggest counselling, for fear of falling afoul of such legislation. Yet medical professionals and regulators should fully expect that detransitioners, those who regret their transition, will be angry and hold to account a medical establishment that refused to inform them fully at the time of their decision about the risks.

In this regard, the experience of the Tavistock Gender Clinic (formally known as the Gender and Identity Development Service (GIDS)) in the UK is instructive. At one time the flagship gender disorder clinic in the UK, the Tavistock has recently been shut down by regulators after a damning independent report (Sex Matters 2022) for precisely these issues: uncritically taking at face value young people’s gender dysphoria and immediately prescribing hormones, “puberty blockers” and even surgery with little or no effort to understand or communicate the risks to their patients. According to The Independent, “Staff, patients and parents have raised concerns that young people using the service were put on the pathway to transitioning too early and before they had been properly assessed.” Massive class-action lawsuits (Lovett 2022) are now expected to be filed against the clinic for failure to respect their professional duties to their patients. One of the lawyers involved, barrister Thomas Goodhead, is quoted as saying that the case “is going to be one of the largest medical negligence scandals of all time” (Times Radio 2022).

The controversies are also emerging in other countries. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, on September 21, 2022, responded to criticisms (Broderick, Davis, Williams, and West 2022) that it profits from and therefore promotes gender transformation in underage youth by announcing that “VUMC requires parental consent to treat a minor patient who is to be seen for issues related to transgender care, and never refuses parental involvement in the care of transgender youth who are under age 18” (Vanderbilt University Medical Center 2022). As a result of the publicity and attention that has been drawn to their activities, VUMC has essentially taken down their website, which critics argue clearly contradicted the clinic’s claims about the safeguards they now claim to apply to transgender care.

Here in Canada, parents of minor children have gone to court to prevent aggressive gender reassignment surgery on a 14-year-old (Graham 2020). Other critics argue that “Canada is too quick to treat gender dysphoria, in minors, with… surgery” (Blackwell 2021). An example is the case of a 16-year-old girl who, while being wheeled into surgery, expressed reservations about the procedure and five years later decided to detransition having decided that despite the double mastectomy she was really a woman (Blackwell 2021).

The problem, as we have noted, is that neither parents, nor clinicians have sufficient research evidence to predict which children will be better or worse off after surgery. And, as previously mentioned in this article, children and adolescents subject to aggressive medical or surgical interventions suffer immediate harms.

At this juncture the very medical professions that should be asking searching questions, and standing up for their members’ responsibility and duty to ensure that their young patients’ interests are fully protected, are trying very hard to suppress discussion of these issues and preventing their members from hearing dissenting views about gender-affirming care (Shrier 2021).

Clinicians are in a quandary: risk the ire of some professional organizations by honestly relating to patients the lack of satisfactory information about the overall benefits and harms of gender transition surgery or put themselves in legal jeopardy when some patients who accepted aggressive therapies suffer and realize that the scientific evidence was insufficient. And for the reasons outlined above, it is difficult for clinicians to predict who will benefit or be harmed by aggressive gender transformation manoeuvres.

Knowing what questions to ask might help

The purposes of health care in general are to improve comfort, function, and life expectancy. And the purpose of mental health services is to influence feelings, thoughts, and behaviour.

What should people with gender dysphoria[1] consider when thinking about complex gender affirming[2] interventions?

First, gender affirming interventions pose immediate and continuing risk to life expectancy and function.

People who transition take supplemental hormones, estrogen or testosterone, which are not compatible with their biological sex. They are exposed to various risks including increased risks of breast cancer for men who take estrogens to transition to woman, and liver disease for men who transition to female. There is also evidence of temporary or even permanent sterility as a result of taking such hormones (National Health Service 2020).

Men who take estrogen for a male to female transition must also take other drugs, like spironolactone, to block the effect of testosterone. Spironolactone interferes with potassium metabolism and increases the risk of blood pressure and heart rate abnormalities, as well as muscle problems. Some transitioners choose to have their testicles removed to take lower doses of estrogen and avoid testosterone blockers. Not everyone responds to hormone disruptors in the same way. The absence of guiding research means it is not clear what measures clinicians should use to decide on the best dose or strategy for each person.

Nor are hormones the only pharmaceutical intervention now raising concerns. The euphemistically named “puberty blockers” – more revealingly described by their correct name, “chemical castrators” – are available in Canada virtually on demand as soon as a minor indicates any interest in gender identity questions. These are not benign drugs but are associated with serious conditions such as early onset osteoporosis (Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine 2021a). Furthermore, since the use of these drugs as puberty blockers is an off-label use, it is important to understand that no proper clinical trials have been carried out on this use of these drugs. Claims that they are inoffensive and their effects perfectly reversible at any time are not borne out by the information we do have about their effects, especially on young people whose bodies are still in development.

Countries such as Sweden and Finland have recently abandoned uncritical gender-affirming care for minors. According to one Swedish account:

This is a watershed moment, with one of world’s most renowned hospitals calling the “Dutch Protocol” experimental and discontinuing its routine use outside of research settings. According to the ”Dutch Protocol,” which has gained popularity in recent years, gender-dysphoric minors are treated with puberty blockers at age 12 (and in some interpretations, upon reaching Tanner stage 2 of puberty, which in girls can occur at age 8), and cross-sex hormones at the age of 16. This approach, also known as medical “affirmation,” has been endorsed by the WPATH “Standards of Care 7” guideline. (Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine 2021b)

The experience is similar in Finland, where independent review established the lack of good evidence in favour of gender affirming care:

A year ago, the Finnish Health Authority (PALKO/COHERE) deviated from WPATH’s “Standards of Care 7,” by issuing new guidelines that state that psychotherapy, rather than puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones, should be the first-line treatment for gender-dysphoric youth. This change occurred following a systematic evidence review, which found the body of evidence for pediatric transition inconclusive.

Although pediatric medical transition is still allowed in Finland, the guidelines urge caution given the unclear nature of the benefits of these interventions, largely reserving puberty blocker and cross-sex hormones for minors with early-childhood onset of gender dysphoria and no co-occurring mental health conditions. Surgery is not offered to those [under] 18. (Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine 2021c)

Second, transitions do not necessarily lead to better lives. Walt Heyer, a former transgender female wrote:

The reprieve I experienced through surgery was only temporary. Hidden underneath the makeup and female clothing was the little boy hurt by childhood trauma. I was once again experiencing gender dysphoria, but this time I felt like a male inside a body refashioned to look like a woman. I was living my dream, but still I was deeply suicidal. (Heyer 2019)

Imagine his resentment if his parents had encouraged doctors to do his transition before he had matured.

People considering transition should be asking tough questions about the proportion of people who benefit or are harmed from such transitions and medical practitioners have a professional duty to make their patients aware of these risks. Sadly, for youngsters such research has not been done, partly because the number of candidates for transition treatments is low and it is difficult to do an appropriate trial.

Curiously, outside the area of gender affirming care, physicians and regulators are themselves cautious and ambivalent about the use of even insignificant amounts of hormones to influence function and appearance.

Men wishing to take tiny amounts of anabolic steroids like testosterone to improve their appearance or athletic performance will have difficulty obtaining steroids from a doctor. Indeed, they might be forced to buy the drugs at their local gym or from a street vendor. The reason is that the medical establishment feels that even low doses of testosterone used for body sculpting might be harmful.

Women asking for estrogens are warned about the increased risk of some cancers and of cardiovascular disease.

The risk of harm from hormone therapy is the same whether the drug is obtained from street vendors, physicians, or pharmacists.

Do some adults benefit?

Some people believe, as adults, they might be happier if they were not their birth sex. Bruce Jenner, the male Olympic athlete, who became the female actor Caitlyn Jenner, is one example and Chaz Bono, formerly Chastity Bono, transitioned from female to male. Fully informed adults under the care of competent professionals are entitled to make such choices and may feel the benefits outweigh the risks, although here again we lack the medical research and data to inform them properly about the consequences of these choices.

Conclusion

Motivated and consenting adults should have the freedom to choose how to live their lives. If clinicians are prepared to offer drug and surgical treatments for gender transition, patients should be free to have them. The regulators’ and lawyers’ responsibility is to evaluate whether clinicians gave the patients, who subsequently changed their mind, the information they needed to make an informed choice. If regulators agree with this rationale then people should be free to ask for and receive other drugs that they believe will improve their experiences, thoughts, feelings, and behaviour including hormones to modify appearance, and drugs, uppers, and downers, such as amphetamines or valium to alter their mood.

Adults and the parents of young children who want to change birth sex face a quandary. Doctors are free to opine on any topic, and many people blindly accept medical advice and recommendations. Most medical suggestions are based in science. Sometimes when science is insufficient, they are based on art. Advice about gender transition for youngsters is one example of such art too often masquerading as science.

When clinicians, making artful suggestions and constrained by conversion therapy bans not to communicate their complete thoughts, offer different and even contradictory conclusions, patients and parents are forced to choose between their opinions and must recognize that majority opinion does not rule. Historically doctors believed that many unscientific treatments were valuable. George Washington had bloodletting for a sore throat and died of anemia, others had radiation therapy for thyroid disease and died from cancer. Sadly, the list of harmful treatments that were widely accepted is not short.

In the face of evidence that some people change their minds, and the clear immediate harms from transition treatments, parents and doctors would be well-advised to support and respect children who claim they are a different gender from the one they were born with, understanding that that does not simply mean acquiescing uncritically in every demand for immediate transition. Professionals and parents should also be clear that some, but not all, people regret invasive and permanent transition treatments and should be advised that proxies (like parents) cannot make such decisions and that the child should wait until adulthood to consider transition and to get information that is current when they decide to explore transitioning.

About the author

David Zitner is a retired family physician, former Professor in the Dalhousie University Faculties of Medicine and Computer Science and the founding director of the graduate program in Health Informatics. He has contributed to the boards and advisory committees of a several Canadian health organizations, including the Canadian Medical Association and accreditation Canada. He has chaired the quality, utilization and other committees of the Halifax Infirmary, a major Canadian teaching hospital. He has published in the popular press and in peer reviewed medical journals and was co-author of the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies Fisher prize winning papers “Operating in the Dark” and “Public Health: State Secret.”

References

Ault, Alicia. 2021. “Transgender Docs Warn About Gender-Affirmative Care for Youth.” WebMD (November 29). Available at https://www.webmd.com/sex-relationships/news/20211129/transgender-docs-gender-affirmative-care-youth.

Blackwell, Tom. 2021. “Canada too quick to treat gender dysphoria in minors with hormones, surgery: critics.” National Post (December 2). Available at https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/canada-transgender-treatment.

Broderick, Kelly, Chris Davis, Phil Williams, and Emily West. 2022. “Tennessee lawmakers weigh in on Vanderbilt providing gender-affirming care.” NewsChannel 5 (September 21). Available at https://www.newschannel5.com/news/vanderbilt-university-medical-center-at-center-of-social-media-controversy-surrounding-transgender-clinic

Canadian Gender Report. 2019. “The Canadian experiment with puberty blockers: what we know so far.” Canadian Gender Report, December 3. Available at https://genderreport.ca/trans-youth-can-study-puberty-blockers/.

Clitoris.io. Undated. “Dr. Marci Bowers MD.” clitoris.io. Available at https://clitoris.io/speakers/marci-bowers.

Graham, Jack. 2020. “Canadian mother blocking trans teen’s surgery fuels age debate.” Reuters (November 14). Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-canada-lgbt-transgender-trfn-idUSKBN27U0PZ.

Heyer, Walt. 2019. “Hormones, surgery, regret: I was a transgender woman for 8 years — time I can’t get back.” USA Today (February 11). Available at https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/voices/2019/02/11/transgender-debate-transitioning-sex-gender-column/1894076002/.

Kattari, Shanna K., Leonardo Kattari, Ian Johnson, Ashley Lacombe-Duncan and Brayden A. Misiolek. 2020. “Differential Experiences of Mental Health among Trans/Gender Diverse Adults in Michigan.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (September 18). Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7557385/.

Lovett, Samuel. 2022. “Tavistock gender clinic facing legal action over ‘failure of care’ claims.” Independent (August 11). Available at https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/tavistock-gender-clinic-lawyers-latest-b2143006.html.

National Health Service. 2020. “Treatment: Gender dysphoria.” National Health Service, May 28. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/gender-dysphoria/treatment/.

Pike, Jon, Emma Hilton, and Leslie A. Howe. 2021. Fair Game: Biology, fairness and transgender athletes in women’s sport. Macdonald-Laurier Institute, December 7. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/biology-fairness-trans-inclusion-sport-paper/

Rafferty, Jason et al. 2018. “Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents.” Pediatrics, 142(4) (October). Available at https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/142/4/e20182162/37381/Ensuring-Comprehensive-Care-and-Support-for.

Ring, Avi and William J. Malone. “Confounding Effects on Mental Health Observations After Sex Reassignment Surgery.” The American Journal of Psychiatry (August 1). Available at https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19111169.

Shrier, Abigail. 2021. “A Pediatric Association Stifles Debate on Gender Dysphoria.” Wall Street Journal, August 9. Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/pediatric-association-gender-dysphoria-children-transgender-cancel-culture-11628540553.

Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine. 2021a. “The Effect of Puberty Blockers on the Accrual of Bone Mass.” Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine, May 1. Available at https://segm.org/the_effect_of_puberty_blockers_on_the_accrual_of_bone_mass.

Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine. 2021b. “Sweden’s Karolinska Ends All Use of Puberty Blockers and Cross-Sex Hormones for Minors Outside of Clinical Studies.” Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine, May 5. Available at https://segm.org/Sweden_ends_use_of_Dutch_protocol.

Sex Matters. 2022. “The Cass Review’s interim report is out.” Sex Matters, March 12. Available at https://sex-matters.org/posts/updates/the-cass-reviews-interim-report-is-out/.

Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine. 2021c. “One Year Since Finland Broke with WPATH ‘Standards of Care.’” Society for Evidence Based Gender Medicine, July 2. Available at https://segm.org/Finland_deviates_from_WPATH_prioritizing_psychotherapy_no_surgery_for_minors.

Szilagyi, Moira. 2022. “Why We Stand Up for Transgender Children and Teens.” AAP Voices Blog (August 10). Available at https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/aap-voices/why-we-stand-up-for-transgender-children-and-teens/.

Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust. 2019. “Referrals to the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) level off in 2018-19.” Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, June 28. Available at https://tavistockandportman.nhs.uk/about-us/news/stories/referrals-gender-identity-development-service-gids-level-2018-19/.

Times Radio. 2022. “Explained: Why Tavistock gender clinic is to be ‘sued by 1,000 families’.” Youtube Video, 5:50 (August 11). Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TofQjUf6jtY.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center. 2022. “Statement about transgender health care at VUMC.” VUMC Reporter (September 21). Available at https://news.vumc.org/2022/09/21/statement-about-transgender-health-care-at-vumc/.

Vesterberg, Jonas. 2022. “AHCA: Alarming Increase in Children Receiving Puberty Blockers.” The Florida Standard (August 29). Available at https://www.theflstandard.com/ahca-alarming-increase-in-children-receiving-puberty-blockers/.

[1] Men and woman who are distressed because they believe their experienced gender identity is not compatible with their birth identity.

[2] Gender affirming medical interventions are ones where hormones, surgery, plastic surgery or all three are used to modify a person’s birth gender to conform with their expressed gender identity.