We still have time to act; we could approve and quickly license and produce rapid tests in Canada by the tens of millions, write John Adams and Kashif Pirzada.

We still have time to act; we could approve and quickly license and produce rapid tests in Canada by the tens of millions, write John Adams and Kashif Pirzada.

By John Adams and Kashif Pirzada, December 15, 2020

Canada’s ongoing failure to effectively control the spread of COVID-19 reflects increasing failures by governments to coordinate with one another and to respond quickly and effectively to new developments and scientific advances. This is abundantly clear in the self-harm inflicted by our original difficulties in sourcing of personal protective equipment (PPE), Canada’s late and flawed strategy for vaccine procurement, and our continuing faulty approach to self-sufficiency in drug manufacturing.

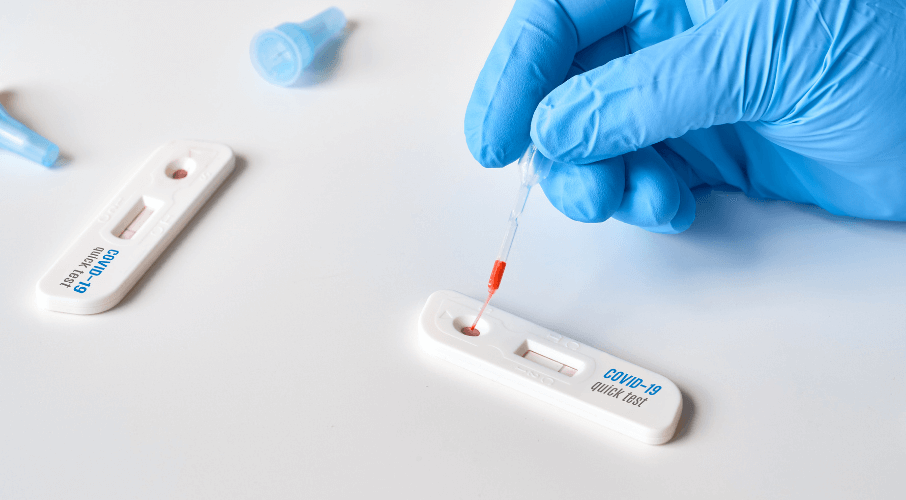

It is the issue of rapid tests that brings this into light most abundantly. Rapid antigen tests are screening tools – very much similar to a home pregnancy test – that can detect COVID-19 at its most infectious. Any screening test has limits and will occasionally miss infections, and thus needs to be conducted regularly, two-to-three times per week, to be most effective. The real world choice is to screen widely and miss a few infections but act on the findings, or not screen at all and miss many infections due to mild or no symptoms. The rapid tests are inexpensive to manufacture, easy-to-use and there are Canadian companies ready to make them. Their advantages have been known for five months at least, since July when Professor Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at Harvard University, began to advocate for their wide use.

Their effectiveness has been quite obvious lately. Europe has been reporting shocking numbers of cases and deaths, but one country is bucking that trend. In just two weekends in October, Slovakia tested every resident between the ages of 10 and 65 using rapid tests. That is a proper use of screening. They locked down the country for two weeks; those that tested negative – the large majority – were given a special pass to move freely. They mobilized every resource, including the military and polling centres in schools, and created thousands of testing teams.

As a result, Slovakia found that 1 percent of the population was infected, and isolated them for ten days. They brought down their R0, a measure of virus reproduction, from 1.47 to 0.62, and they are the only country in the world now reporting a decrease in cases. They did not use these tests as a surrogate for diagnostic PCR tests, which they are not, but used them instead as an effective mass screening tool.

Resistance to use of these tests for screening comes from multiple levels. Let’s look at the four barriers. The first is at the public health agencies, where a new technology has been met frostily by those too busy fighting fires in their own regions, or fixated on comparing these screening tests to diagnostic tests not distinguishing apples from oranges, or wedded to older paradigms and methods and resist change for the sake of resisting.

How ironic and sad that some public health experts cannot deal with the different roles of screening and diagnosis. We are seeing this in British Columbia, where a pilot project in using rapid tests is being met with opposition by provincial authorities. This is not universal, as authorities in Halifax successfully used these tests as designed to quickly suppress a burgeoning outbreak. Sadly, successful examples like this do not scale or percolate through our insular health silos across the country.

The second level is at the provincial political level, as very few provinces have shown an interest in the technology, and those that have, as in Ontario, have been stymied by a lack of supply. Provincial governments lack the sophisticated advisory bodies like the National Research Council or Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council to obtain scientific advice, and few politicians or political aides have the scientific credentials to evaluate new discoveries and technologies and override system inertia.

The third barrier is at the federal level, where you have the political side eager to obtain and use these tests, but hamstrung by a health regulator they are loath to interfere with. Health Canada has approved very few rapid tests, and those approved all have impressive capabilities in terms of sensitivity and specificity (measures of accuracy). However, other excellent screening tests are languishing in the queue for approval, even though they are already being used in Europe and the US, whose competent regulators have verified their excellent performance characteristics. One company we spoke to is marketing a made-in-Canada test, but is faced with a months-long process and ever-increasing evidentiary requirements.

The final barrier is the market, where more savvy governments are quickly buying and monopolizing testing supplies that are available. Canada’s government response, which is fragmented between levels and limited by an inchoate strategy, cannot hope to compete in this arena. Canada has received four million Abbott rapid tests from abroad, and is unlikely to receive more anytime soon. The number sounds impressive, but the true need is in the tens of millions.

We could have licensed production here in Canada, as Roche did with a South Korean test from SD Biosensor, and set up contract facilities in the months that we had, but sadly nothing was done. With a pro-rapid-test incoming CDC head in the US under the new Biden administration, you can be assured that every last stock of these tests will be poured into an insatiable US market.

Vaccines are on the horizon, but a full rollout of these will take far into the summer months for most Canadians. In the meantime, we face real hardship in controlling these infections. Targeted closures are effective but cases are still rising. A blunt full lockdown will not be effective on its own for very long; Brampton, the hardest hit city in Ontario, has hundreds of transport, industrial and food processing businesses critical to supplying the country. Truckers, who are exempt from 14-day quarantine rules, are constantly moving back and forth from the US and will simply reseed infections again. This is predictable.

We still have time to act; we could approve and quickly license and produce rapid tests in Canada by the tens of millions. Every Canadian can test themselves twice weekly for the early months of January, and we can emerge from our lockdowns and resume contact tracing and targeted measures while vaccinations occur. We can try, almost, to live life like our brethren in Atlantic Canada, where shops, restaurants and gyms are open, normal life continues, and that omnipresent fear isn’t there.

Sticking with the status quo means we live with increasing cycles of lockdowns, re-openings, disrupted holidays, distant family and constantly living in fear, which exacts its own toll. The choice is clear, fight our collective government dysfunctions for a better future for all Canadians or be passive, defer to authorities and suffer unnecessarily.

John Adams is volunteer board chair of the Best Medicines Coalition of 30 patient organizations and co-founder/CEO of Canadian PKU and Allied Disorders. Dr. Kashif Pirzada is an Emergency Physician in Toronto, is affiliated with McMaster University and the University of Toronto, and is co-chair of Masks for Canada.