This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, March 28, 2025

Both the Liberals and Conservatives have rolled out plans to cut income taxes. Each focuses on the first tax bracket—the one that applies to the first chunk of income most Canadians earn.

The Liberals want to lower that rate from 15 percent to 14 percent. The Conservatives would go further, dropping it to 12.75 percent.

At first glance, that sounds like good news. More money in people’s pockets. And yes, these cuts will raise disposable incomes for most Canadians. But when it comes to boosting economic growth, investment, or job creation? Don’t expect much.

Before getting to that point, let’s start with the basics of what these plans mean for Canadians directly.

The value of income tax cuts

The impact on families is fairly straightforward to estimate. I looked at the Liberal plan earlier, and now that we have the Conservative proposal, we can compare the two.

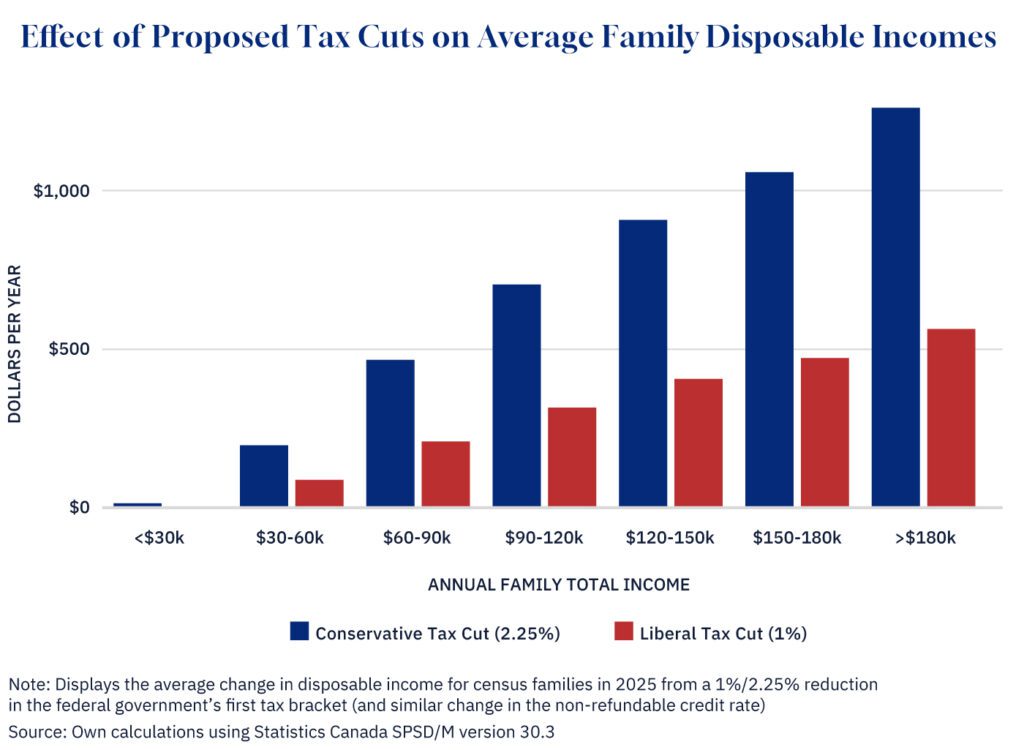

The Conservative plan is worth more, naturally, since it cuts the rate by more. On average, it provides about $575 per family, compared to about $255 from the Liberal plan.

But there are important differences across individuals and families.

Some won’t pay less tax at all since they don’t pay any to begin with. I estimate approximately one-in-four households will see no change in their after-tax income as a result of either the Liberal or the Conservative plan.

Among those that do pay taxes, some benefit more than others. If you claim a lot of tax credits, you’ll benefit less (but, of course, you pay a little less in income taxes to begin with). And if your family has multiple income earners, you’ll benefit more (since, of course, your family pays more income taxes). This means that higher-income households tend to get a bigger benefit in dollar terms. That’s partly because they claim fewer credits (which means the tax cut applies to more of their income), and partly because there may be more earners in the household—each of whom gets the cut.

How large of a tax cut?

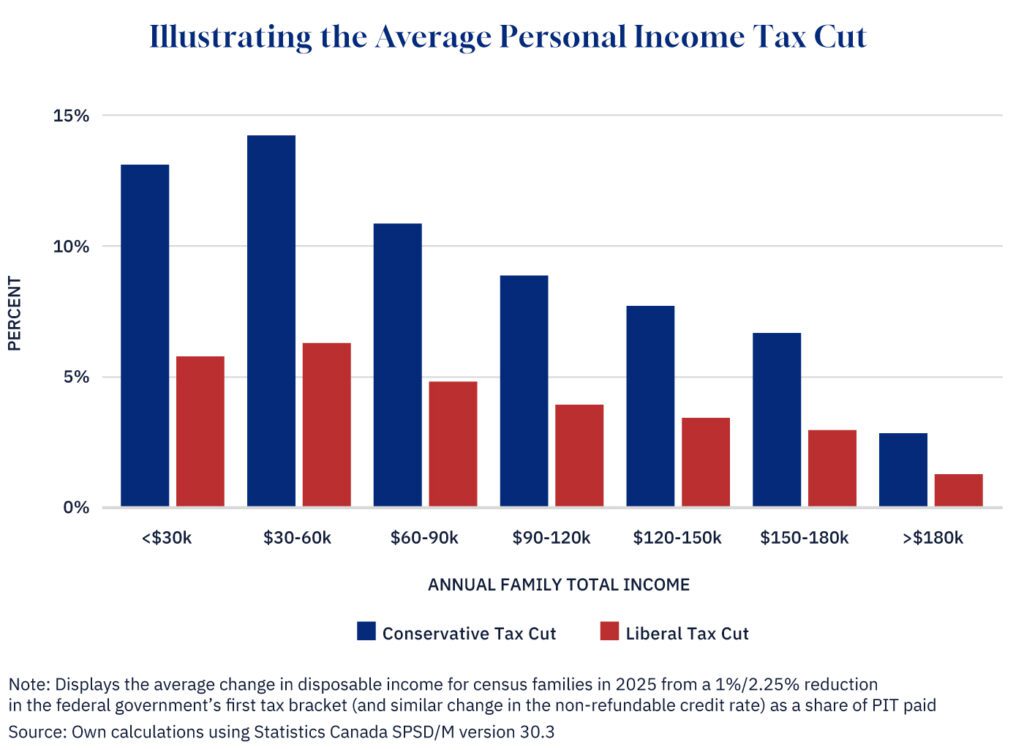

Another way to think about this is not in dollars, but in terms of taxes that you pay. The Conservatives market their plan as a 15 percent tax cut “for the average Canadian.” That’s not entirely accurate, but for some it’s pretty close. Below I estimate the percentage reduction under both parties’ plans as a share of federal income taxes paid.

For families earning between $30,000 to $60,000, I estimate that the average personal income taxes paid under the Conservative plan would fall by just over 14 percent. And across all families, the effect reduction in average income taxes paid would decline by approximately 5 percent under the Conservative plan and by just over 2.2 percent under the Liberal plan.

At what cost?

Both plans come with a cost to government. I estimate the Liberal plan would reduce government revenues by about $5 billion. The Conservative plan could cost roughly $11 billion.

How will they pay for it? The Conservatives were clear—they’d cut spending. And to be fair, $11 billion is a manageable number in the context of the $500 billion federal budget.

But the federal budget has other pressures too. An aging population means rising costs for seniors’ benefits—costs that the current government recently increased. There’s also growing pressure to boost defence spending to meet international commitments Canada has long fallen short on.

What’s more, these tax cuts aren’t a great tool to tackle affordability—the issue both parties say they’re trying to address. Targeted help for lower-income households would go further. For instance, boosting the GST credit would be more effective. It’s technically a consumption tax cut, and it delivers more support to those who need it most.

Ontario offers an interesting example. After Premier Ford’s election, the province made changes that mean many people earning under $30,000 now pay no provincial income tax at all. That’s a cheaper move and one that better targets affordability challenges.

So what about growth?

Since these cuts only touch the first bracket, they don’t change the marginal tax rates faced by middle- or high-income earners. That matters, because marginal rates affect the incentive to earn more, take on extra work, or invest. In many provinces, top earners still lose more than half of each extra dollar they make to taxes.

That’s a challenge—for attracting talent, for encouraging work, and for investment.

Broad-based tax reform, done right, could make a bigger difference. You could use the same amount of money to lower marginal rates or make changes to business taxes that help drive investment and productivity. But by locking in these first-bracket cuts, governments leave themselves with less room to do that.

Of course, we’re still early in the election cycle. The parties might have other ideas yet to come. And hopefully so, as Canada’s economic performance in recent years has lagged far behind our peers.

But based on what we’ve seen so far, these tax cuts—while good politics—won’t move the needle much on the economy.