This article originally appeared in the Financial Post.

By Darrell Beaulieu, Paul Gruner and Heather Exner-Pirot, December 6, 2023

Although it wasn’t much noticed in the rest of Canada, the Northwest Territories had an election last month. Worn down by a series of crises, people voted for change: about half of the MLAs-elect are new. They picked a hard time to get into government. Compared to what’s coming next, COVID-19 and record-breaking wildfires might not look so bad. The territory’s diamond mining industry, which represents over a quarter of its GDP, is coming to its natural end. And as things stand there is no plan to replace it.

Southerners see the N.W.T. as a vast, cold territory with untapped resources. Many seem to assume that as the energy transition increases demand for critical minerals the territory can simply ramp up production as needed. But the mining business is more complicated than that, and nowhere are the economics and logistics of resource development more challenging than in Northern Canada. Inadequate infrastructure, a small labour force, a complex regulatory framework and high costs can discourage potential investors. Canada’s recent reputation as a difficult place for resource development doesn’t help.

The mining industry that does exist in the N.W.T. today is almost wholly in diamonds. The territory is the world’s third largest producer of the precious stones, with output of $2.2 billion in 2022. In a territory of just 45,000 people, that has enormous economic impact. Diamond mining represented 27 per cent of the territory’s GDP in 2022, more than the share of oil and gas in Alberta’s economy.

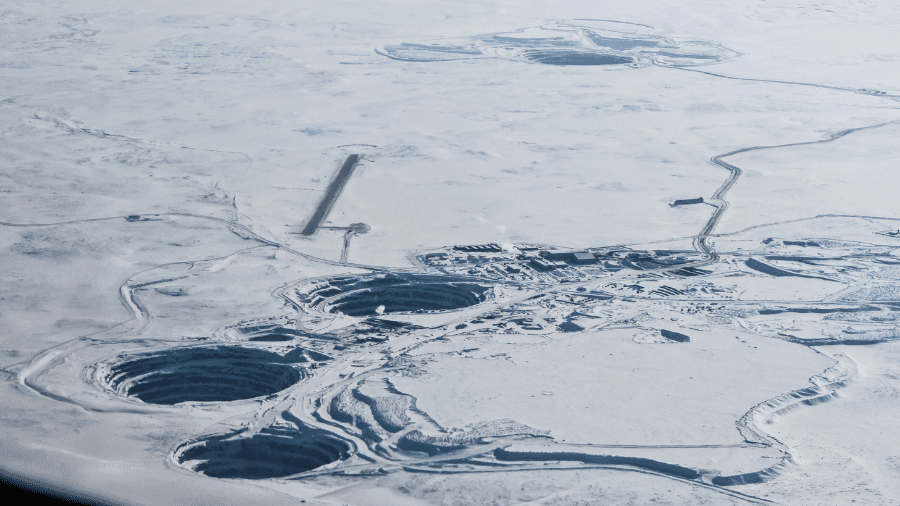

Production is concentrated in three mines: Ekati, Diavik and Gahcho Kué. Diamonds may be forever but mining them isn’t. All three mines will reach their end-of-life by 2030, with most production stopping well before then.

Much of the territory’s Indigenous business sector has grown up around diamond mining. Last year, the three mines spent well over a third of their $1 billion in procurement on Indigenous businesses. Cumulative spending on Indigenous business since 1996 has been over $8 billion. These businesses have built up capacity, skills and assets over that time that could be leveraged into even bigger and better contracts if new projects were developed. The fear is that if no new opportunities present themselves, they and the territory will lose these skilled workers and contractors to other parts of the country.

A handful of medium-sized mines are in various stages of development in N.W.T., poised to meet some of the anticipated global demand for critical minerals, including zinc, rare earths and lithium. But it’s far from certain they will all go ahead.

Despite knowing the N.W.T. economy is about to fall off a cliff, the territory’s government has done little to attract new investment. The N.W.T.’s geologic heritage and economic potential are tremendous. As we enter a new commodities cycle, options will present themselves. But the territory should not sit waiting for opportunities to come to it.

Later this week the 19 newly elected members of the assembly will meet as a caucus to determine their shared priorities. They will then vote to select their next premier and cabinet. One of the new government’s first orders of business should be to gather with Indigenous leaders and the mining industry to identify priorities and develop a plan of attack. The next step would be to meet with the federal government to devise and implement a strategy that results in economic and resource benefits for the North. This would signal both to investors and to Ottawa that the territory is serious about new investment and willing to act quickly and in close collaboration with Indigenous nations.

At least three things should be on the territory’s mining agenda:

Streamline permitting and regulation. This needs to include capacity support so Indigenous nations can do their own due diligence and provide timely and informed feedback regarding proposed projects.

Support investment in energy and transportation infrastructure. Financing for Indigenous development corporations needs to be a priority. But direct federal investment in projects — for example through Ottawa’s new Critical Mineral Infrastructure Fund — will also be needed.

Maximize Indigenous mining input. The workforce and supply chain that have been built up over the past two decades for both construction and operation of new projects are a good base on which to build.

If in any other part of Canada a quarter of GDP were scheduled to disappear within seven years, alarm bells would be deafening. Instead, both Yellowknife and Ottawa have been approaching the industry’s imminent demise with at best benign neglect. The problem barely registered in this past election.

Given the timelines involved, the incoming territorial government will be the last with any real chance to both manage the end of the diamond mining sector and seek investments to replace it. It is time to stop sleepwalking toward economic catastrophe and work with Indigenous business and communities to offset it.

Darrell Beaulieu is CEO of Denendeh Investments Inc. Paul Gruner is CEO of Tłı̨chǫ Investment Corporation. Heather Exner-Pirot is director of energy, natural resources and environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.