While boil water advisories are down, real reform is required to give Indigenous communities control over water safety and bring quality up to national expectations, writes Joseph Quesnel.

While boil water advisories are down, real reform is required to give Indigenous communities control over water safety and bring quality up to national expectations, writes Joseph Quesnel.

By Joseph Quesnel, February 4, 2019

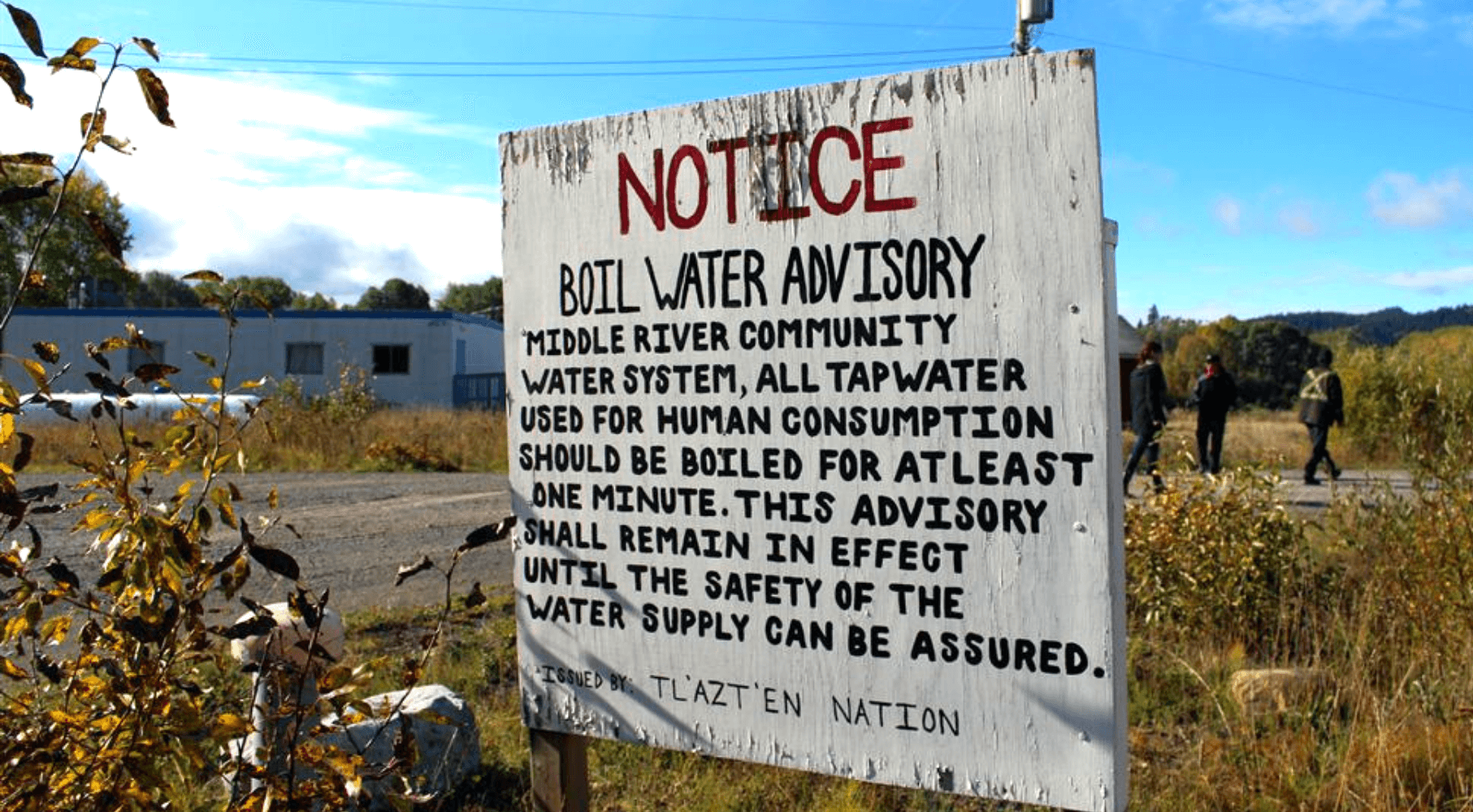

The Liberal government recently announced that it was on track with reducing long-term boil water advisories on First Nations in Canada – and that they will meet their target of eliminating them completely by 2021. This is indeed good news and should be celebrated, even if short-term advisories continue to be a problem for many First Nations.

Indigenous Service Canada’s website reveals that 79 long-term advisories were cancelled since November 2015. When the Liberals took office, there were 105 advisories.

For First Nation communities, safe drinking water – or more appropriately the lack of it – has become a national moral issue and a scandal for Canada, and it should be treated as such.

The federal commitment to quality drinking water for all First Nation citizens should come before access to broadband Internet. People need to be safe and healthy before we worry if they can surf the Web.

This government needs to tackle not only funding for water and wastewater infrastructure, but also the legislative gap and the central governance problem associated with water delivery. Addressing the governance issue is the elephant in the room.

From the outset and to be clear, the governance problem is not that Indigenous communities cannot handle their own water systems or that this problem is evidence of corruption. It is the opposite. The problem is that First Nations are truly not able to control their own water systems.

First Nation communities need the proper tools and authority to handle their own drinking water issues. They also need to handle these basic infrastructure matters so that they can be perceived as credible and trustworthy governments, which is good for outside investors and resource partners.

For some perspective, one Indigenous community in Northern Ontario has had an advisory since 1995. Talk about “long term.”

Non-Indigenous Canadians take safe drinking water for granted. This is especially the case after the infamous tragedy in Walkerton, Ontario in which individuals died as a result of contaminated water. Since Walkerton, provincial governments have enacted serious reforms to protect water quality. The Walkerton tragedy really revolutionized our systems. We now have multi-barrier systems to prevent contamination.

First Nations, however, have been left behind on these reforms, largely because they do not come under provincial jurisdiction on these matters. There was a legislative gap where First Nations were under federal authority and a patchwork of government ministries were responsible for First Nation water.

As some observers caution, there are Indigenous Walkertons just waiting to happen on some First Nations.

The sad truth is it has already happened. In the early 1980s, eight children in the Cree communities of Waskaganish and Nemaska died from gastroenteritis likely caused by contaminated water from a central well.

Indigenous water issues also made the news in 2005, when Kashechewan First Nation, located near James Bay in Northern Ontario, had to evacuate 60 percent of its community due to a misdiagnosis of a simple water operator problem.

It would simply be irresponsible, however, to argue that the federal government – of both stripes – has not acted to prevent a First Nation Walkerton from ever re-occurring. Landmark investments have been made. And, under the Conservatives, a Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act was finally passed that attempted to create enabling legislation to address the regulation gap and provide a legislative base that was lacking.

As stated above, the governance problem on reserves is not that First Nations lacked the ability – if given the tools – to operate their own water systems. Rather, they lacked the resources or the know-how to hire trained and certified water operators who could do the necessary inspection and water testing.

Informed observers have also blamed the problems on the challenges of operating a small system. Some argue that provincial water policies should allow for the consolidation of smaller water systems into larger, more viable ones. It is an issue of scale. According to a 2005 report from the Water Strategy Expert Panel, the US Environmental Protection Agency states that a minimum of 10,000 customers is required for a viable drinking water system. Of course, no single First Nation in Canada can meet that.

The problem with the Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act – particularly from an Indigenous government perspective – is that it was all about federal mandate and was not Indigenous led. It did not recognize First Nation authority over water. For many Indigenous communities, that was a non-starter.

While an argument can be made that Ottawa must act to protect water safety for all Canadians, there is strong evidence that Indigenous governments at the local level must ultimately operate these systems, when they have proper infrastructure and standards. The federal government does not have a good record of being a supplier of services, such as water. They are distant and unresponsive to problems.

A model moving forward is the Atlantic First Nations Water Authority, a new utility body created by the Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs (APC-FNC), which oversees First Nation communities in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. The authority is moving towards common standards to protect water and it aims to reduce the cost and management burden of each individual band operating separate systems, which addresses the scale issue mentioned before.

The government has not developed regulations under the Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act and has now engaged in a First Nation-led review and input process to gather concerns about the current Act and work to find solutions moving forward. The engagement sessions are expected to start this February.

As in the areas of education, land management, and access to capital, the remedies for the First Nation water woes seem to come from voluntary opt-in legislative frameworks that are often rolled out regionally. When the government moved to possibly amend the Act, the Atlantic First Nation Authority approach should be seriously considered for adoption across Canada where it can be tailored to regional circumstances.

Perhaps one model to follow is that of recent matrimonial property rights legislation on reserves. Ottawa felt it had to move on a critical moral and rights-based issue where Indigenous women were not protected by provincial rules that governed equal division of property in case of marital breakdown, largely because reserves were federal concerns. However, to address the pressing issue of Indigenous jurisdiction, they allowed a system where federal rules would apply until the Indigenous community had adopted its own matrimonial property laws.

Ottawa must deal with these operational and fiscal issues before it finally addresses the so-called regulation void. But ultimately it must address the elephant in the room, which is the governance issue.

Canada must never again experience another Walkerton. First Nations right now know that only too well.

Joseph Quesnel is program manager for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Aboriginal Canada and the Natural Resource Economy project.