This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Rob Huebert, June 20, 2022

The resolution of the Danish-Canadian Hans Island dispute is being recognized as an important step forward in resolving one of our enduring Arctic sovereignty disputes. But many of the media accounts of the dispute omit an important part of the story.

There is a narrative that is now being developed about the history of the disagreement over Hans Island. The first part of this narrative is that the dispute was characterized only by an ongoing, good-natured exchanged of flags and alcohol. While this makes for good stories, it leaves out a very important and troubling part of the history.

In 2002, the good-natured exchanged of booze and flags that had characterized the dispute was completely upended when the Danes used an ice-capable frigate, the HDMS Vaedderen, to land troops on the island. Despite Canadian pleas not to repeat these escalatory actions, they did it again in 2003 with her sister ship, the Triton.

In 2005, then-minister of national defence Bill Graham landed with Canadian Forces personnel on the island. As he makes clear in his memoirs, it was very challenging to get there because the Canadian Navy lacked ships capable of transiting the ice. But the effort was worthwhile, because it was only at this point that the Danes stopped deploying military forces to the disputed island.

Why does it matter that the recent media stories about the settlement leave out this part of the story? It is important because Denmark’s shift from using civilian officials to leave flags and alcohol, to making its point using a warship with troops is escalatory in a serious manner. When this has happened in the South China Sea, fighting has occurred and lives have been lost.

Granted, there is no question that the relationship between Canada and Denmark is not the same as the relationship between China and the other states it has engaged in the South China Sea. But the fact that the Government of Denmark felt it was necessary to do it two years in a row and only stopped when Canada followed suit with its own troops underlines the seriousness of the Danish actions. To pretend that this did not happen is to pretend that Denmark was not using gunboat diplomacy against Canada, which of course it was.

There is a second overtly political narrative that is also being propagated, which is that Stephen Harper was the only prime minister who stood in the way of a settlement. Given the long-term nature of the dispute — about half a century — it seems a little bizarre to blame one prime minister. But the more important omission is that Denmark had the maritime capability to get to Hans Island, but Canada did not.

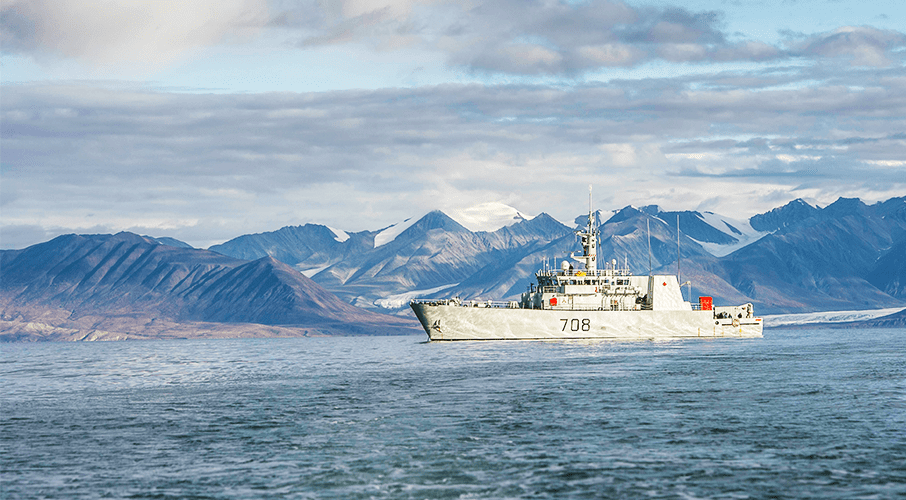

Unlike Denmark, Canadian leaders had never thought it necessary to equip the Royal Canadian Navy with icebreakers or ice-capable vessels. This lack of capacity was noticed and addressed by the decision of the Harper government to build a class of Arctic and offshore patrol ships that now give Canada the ability to get to Hans Island and respond to any future instances of gunboat diplomacy in the Arctic.

Why does this matter given that the problem of Hans Island has been solved? First, Canada will need to engage Denmark in negotiating over the boundaries dividing the extended continental shelf. Its use of gunboat diplomacy over Hans Island demonstrates that the Danes take their negotiating position very seriously and Canada needs to be careful not to underestimate Danish diplomacy.

They will not use their frigates in such a dispute, but Canada needs to realize that they will seek to maximize their position and the fact that we are friends will not mean that they will cut us any slack. They may be small, but they understand power politics.

Second, and more importantly, Russia’s intensification of its 2014 invasion of Ukraine has caused all northern nations to take stock of their need to improve their northern defences. As Canada’s Liberal government reluctantly moves to modernize NORAD, it is becoming clear to many observers that it is necessary to include Greenland, and hence Denmark, in any effort to properly defend against new Russian weapons systems, such as hypersonic missiles.

Hopefully, the settlement of the Hans Island issue, along with an understanding of the whole history of the dispute, will remind Canadian political elites that Denmark may be small, but that it is tough and needs to be included in discussions about protecting the Far North from foreign threats.

Rob Huebert is an associate professor of political science at the University of Calgary and Senior Fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute.