Writing in Diplomat and International Canada magazine, MLI Managing Director Brian Lee Crowley argues that the common perception of Sweden as a staunchly socialist society is increasingly out of date. Crowley cites numerous reforms that have left Sweden with lower taxes, a commitment to balanced budgets, and more private-sector competition. Crowley writes that “while Sweden’s degree of socialism depends a little bit on what you mean by that term, there is little doubt that it has been furiously backpedalling from many of the nostrums of social democracy for decades”.

Swedish Prime Minister John Fredrik Reinfeldt

For many Canadians, “Sweden” and “socialist” have simply always belonged together in the same sentence. Today that is still true, but the sentence now reads, “Sweden is no longer socialist.”

For those who haven’t followed political developments in this Scandinavian country in recent years, such a statement may seem improbable and even outlandish, a bit like saying winter has ceased being cold. The two just seem to go together.

But while Sweden’s degree of socialism depends a little bit on what you mean by that term, there is little doubt that it has been furiously backpedalling from many of the nostrums of social democracy for decades. Moreover, it has been doing it in a typically low-key, off-hand sort of way that belies the profound nature of the changes sweeping the country.

The Sweden of socialist lore never did have a huge share of the economy owned by the government. What it did have was some of the highest taxes in the industrialized world (a top marginal income tax rate of 87 percent), one of the most elaborate offerings of social services of any welfare state, from childcare to social welfare to pensions, and monopoly control by the state in the provision of those services, giving the highly unionized public sector workers huge bargaining power. Each one of these pillars of Swedish socialism has come under concerted attack in recent decades.

Taxes and the size of government

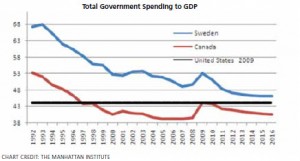

Start with the tax burden. Social democracy Swedish-style was premised on the idea that ownership of the means of production was largely irrelevant; what really mattered was who got to decide what to do with the wealth the economy generated. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), at its height in 1990, Sweden’s total tax burden (i.e. all taxes combined) as a share of the economy (or GDP) was more than 52 percent. After a near quarter-century of decline, it now clocks in at 44.3 percent. Total government spending peaked at roughly 68 percent in 1994 (when the budget deficit was 11 percent of GDP) and has fallen by 20 percentage points. That’s still higher than Canada, for example, but the scales have tipped decisively in favour of allowing private citizens and firms to control the majority of economic decision-making.

St. Göran’s Hospital, Sweden’s largest, was privatized more than a decade ago.

The size of the tax burden was a critical component in finally driving Swedes away from the big government status quo. While the top marginal rate for personal income tax reached 87 percent at its peak, that was not the end of the tax take. In fact, combining all taxes (including on income from capital and small business earnings, for example) marginal tax rates could reach more than 100 percent for those with high incomes. Children’s author Astrid Lindgren (of Pippi Longstocking fame) wrote a famous article in 1976 showing her effective marginal tax rate was 102 percent. She was actually losing money on selling additional books. That article was widely seen as a contributing factor to the defeat of the Social Democrats in 1976 after 44 years in power.

Personal income tax has fallen, with the top marginal rate now still an eye-watering 56.6 percent, but the government’s long-term goal is to reduce it to 50 percent. Corporate income tax, too, has fallen, with Sweden taking 22 percent of profits, well below Canada’s target of a combined federal and provincial rate of 25 percent. Death duties, wealth and property taxes have been eliminated altogether. Consumption taxes remain high, but the total burden is down, with Sweden relying on a more sensible mix of taxes than Canada.

At the same time it has been reining in taxes, the Swedish government has been committing itself to balanced budgets, which are already back after a brief period of recession-induced stimulus spending. And that stimulus spending chiefly took the form of tax cuts, not higher public spending on services and public works.

A Sweden committed to socialism might have been expected to balk at such a major slimming of the state. But Swedes understood that their predilection for massive taxation and government spending had actually undermined their standard of living. The fourth wealthiest country in the world in 1970, Sweden had fallen to 17th by 1993. And since the beginning of Sweden’s massive reforms, economic growth has responded positively,

although unemployment remains relatively high in Swedish terms at just a touch more than eight percent.

When the current conservative government was re-elected in Sweden in 2010, it was largely due to the success of the government’s policy of cutting taxes and reducing welfare to pay for it. For a society whose hallmark had been high taxes in exchange for cradle-to-grave social services, this, too, was a remarkable reversal.

Welfare state reform

Welfare state reform hasn’t just been a matter of cutting benefits, although there has been some of that. Much more important, Sweden has been at the forefront of subjecting formerly monopolistic public services (schools and hospitals, for example) to the bracing winds of competition.

As in Canada, health care used to be the almost-exclusive preserve of the public sector. No more. The change was symbolized by St. Göran’s Hospital, Sweden’s largest, which was privatized more than a decade ago. More than 200 clinics have been set up by private health-care providers around the country and Swedish health-care consumers have a wide array of choices.

Interestingly, former state employees have been at the forefront of the changes. Instead of obstructing the move to more private provision, for example, the nurses’ union became one of the loudest voices pushing for its members to be able to opt out and create their own professional services companies, offering their services on negotiated terms to public and private providers.

Parents in the Swedish education system have similarly been empowered to opt out of the public system, with what is essentially a universal voucher. The large majority of new schools in Sweden come from private providers. While there have been widely publicized problems with individual schools, what the critics forget is that a voucher-based system gives parents the power to shift their child to a more satisfactory school, whereas under the old system of public-sector monopoly, the state decided what school children would attend and there was little ability to avoid poorly performing schools.

Pensions, too, have been reformed. Like many western countries, Sweden was seduced by the old pay-as-you-go model under which today’s pensions were paid out of the pension premiums of current workers, with no reserves being set aside against future pension obligations. It is a system that can work when the labour force is expanding, but not when it is crumbling throughout the West under the weight of aging populations.

Sweden not only put its pension system on a more secure, savings-based track, but also specifically tied future benefits to future economic conditions. Instead of making unqualified promises that pensioners will recieve a given level of benefit, the Swedish government has made it clear benefits will be adjusted if their planning assumptions do not pan out.

As for those cradle-to-grave benefits such as social welfare and unemployment benefits, access has been tightened and benefit levels cut. And in accordance with their famous Lutheran work ethic, the Swedes press benefit recipients hard to return to work at the earliest possible moment.

Critics on the left, who yearn for the old days, try to make out that Sweden is abandoning its long-standing commitment to egalitarianism with these reforms. While the direction of the reforms is clearly towards a more market-friendly system, one also has to put those reforms in context. The starting point was one of a huge state and public services designed to protect the poor.

The reforms have tempered, but not eliminated, these egalitarian leanings so that, according to The Economist: “Once you allow for the progressivity of public services, the OECD reckons, Sweden’s Gini [coefficient, a widely used measure of inequality] drops to 0.18. That still leaves it as the world’s most equal place, as well as one of the fastest-growing and fiscally stable countries in the rich world.”

In other words, socialism in Sweden is hardly dead, but it is no longer an article of faith. Swedes have demanded that high taxes and generous public services be subject to stringent analysis to see whether they really contribute to a higher standard of living. The answer seems to be that Sweden had too much of a good thing and governments of all political stripes that have pursued these changes have enjoyed widespread backing from the public.

That’s not to say that there aren’t dissenting voices. But when the Social Democratic Party, the architect of Sweden’s original welfare state, now campaigns against the centre-right government on the grounds that it has not done enough to create an entrepreneurial culture in Sweden, you know things can never go back to the way they were.

Brian Lee Crowley (twitter.com/brianleecrowley) is the managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, an independent non-partisan public policy think-tank in Ottawa (www.macdonaldlaurier.ca).