[Ed. In the following extract, Tupper reminisces about the difficulties he faced as Premier in carrying Confederation. The speech is perhaps most noteworthy for its description of Tupper’s reconciliation with Joseph Howe, the most formidable opponent of Confederation in Nova Scotia and in 1868 the leader of a delegation to London seeking repeal of the Union. Better terms for Nova Scotia led to Howe’s entry into the federal cabinet of Sir John A. Macdonald in 1869 as President of the Council. Tupper comments: “I knew the man; I knew his patriotic sentiments. I knew him too well not to know that when the time came when it was clear that his hostility would do nothing but injure his country, he would sacrifice himself, if need be, rather than do anything to prejudice the interests of the Province.”]

Published in Halifax Evening Mail, June 16, 1883

Then came the great question of Confederation. I had concerted a measure for the union of the Maritime Provinces. I had felt at the outset how important it was that the provinces of which British North America was composed, should form a united whole. I was invited in 1860, when in Opposition, to lecture before the Mechanics’ Institute in St. John, and I chose for my subject the political condition of British North America. On that occasion I pointed out what appeared to me the glaring defects which existed in our position and I proposed for these provinces a Federal Union such as now exists. I pointed this out as being the only feasible and practicable plan of removing these defects and difficulties and placing the government of this country upon a proper foundation.

I did not believe then that the time had come when it was possible to adopt such a measure. I believed that there were difficulties lying in the way that would render such a Confederation impossible for some time to come, but I believed that one of the best steps towards it would be the union of the Maritime Provinces; and I concerted with the governments of Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick the passage of a joint resolution for a conference at Charlottetown in relation to that question.

Well, the politics of Canada, as my hon. friend Sir A.T. Galt well knows – and no person is better acquainted with the matter, for he was a prime mover on that occasion – presented very great and serious difficulties, and my hon. friend brought forward and propounded in that Parliament the project of a confederate union of all these Provinces, to have all the different Provinces of British North America united together. Taking advantage of the conference which we had called at Charlottetown, these gentlemen sailed down upon us, and one fine morning they came in upon our conference and asked us if we would allow them to present a broader scheme than that which engaged our attention.

I need not tell you that when a gentleman of the great ability and plausibility of my hon. friend Sir A.T. Galt has an opportunity to state a case, he states in in such a manner as to make it extremely attractive, and when we had heard Sir John A. Macdonald, the late Hon. George Brown, Sir George Cartier, and Sir A.T. Galt, we came to the conclusion that it was our duty, as public men, to give the fullest and fairest consideration to the great question, not merely of the union of the Maritime Provinces, but of a united British North America.

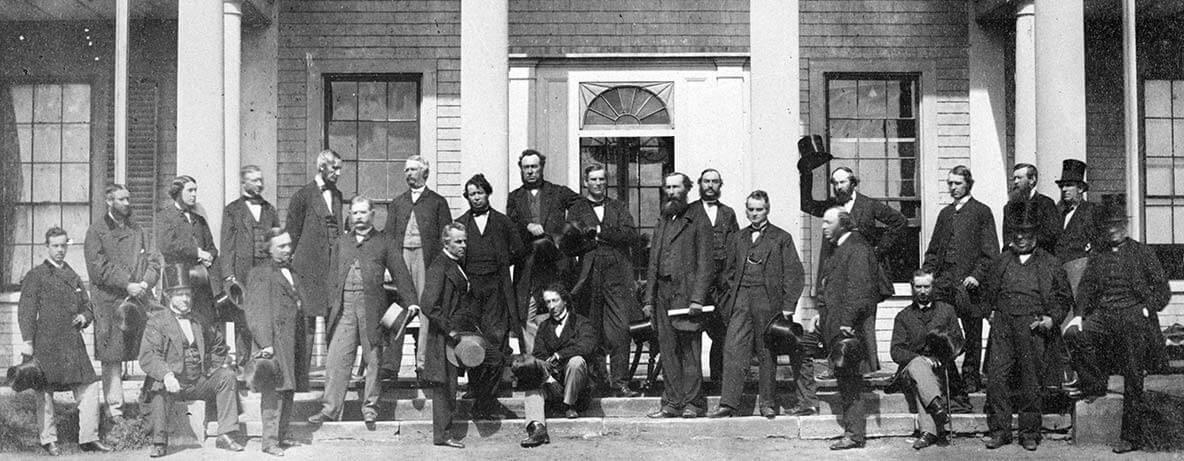

Then we adjourned the conference and came away, and I think it was in this room that I had the honor to receive these gentlemen as our guests. It was in this room that the Hon. George Brown made that able and exhaustive speech, which is not forgotten to this day, in favour of a confederate union of the Provinces. It was in this room that my hon. friend Sir A.T. Galt dealing with the great financial questions connected with that great measure attracted and riveted the attention of all hearers, and led us one and all to believe that the time had come and was propitious to giving the fairest and fullest consideration to that measure.

You are as familiar with the various steps in the progress of that question as I am myself. You know that we went to Quebec and after some three or four weeks of careful deliberation propounded a scheme for the union of British North America which substantially is the constitution of the country today. It is true it received some modification at a subsequent period at a conference at Westminster Palace Hotel in London, but the constitution of the country today is substantially that which, after three or four weeks of deliberation, the public men of the various provinces of this country devised at the then seat of the government of Canada, in the old historic city of Quebec.

I need not weary you or detain you tonight by referring to the long and arduous struggle we had with that measure, – the hostility with which it was met, and the difficulties I encountered on coming back here, and the impossibility of carrying the measure either in the Province of New Brunswick or Nova Scotia. But I may say this that such were the inherent merits of the scheme that the longer the cool, dispassionate, solid men of the country looked at it, the better they were prepared to entertain it, and at no distant period, in 1866, the measure was carried by a two-thirds vote of the House of Assembly and a two-thirds vote of the Legislative Council, when the conference in London matured and agreed upon a scheme.

I will not detain you by referring to the fact that we were not unmindful of the material progress of the province in the meantime. In the first speech which I ever made on the floor of the House of Assembly I committed myself, and so far as I was able the party with which I was connected, to the policy propounded by the late Mr. Howe of carrying out the construction of the railways of this Province as government works, and on every occasion, whether as a delegate in England or in the Legislature of this country, I advocated the pushing of that work to a conclusion.

When the Government, of which I was a member, was called to power, I think there were nine miles of railway in operation in Nova Scotia, from here to Bedford. Before I resigned the position of leader of the Government in 1867 I had carried the railroad to the Gulf of St. Lawrence on the one hand, and had provision made for its extension to the waters of the Bay of Fundy at Annapolis on the other. Under the Confederation arrangement we had further provided for the extension of the line to the adjoining Province of New Brunswick connecting with the rest of Canada and the United States of America. As I stated before, we addressed ourselves vigorously and enthusiastically to that which I believe was absolutely demanded in the best interests of this country.

It has been said at times that I made a mistake in not obtaining the services of that great and eloquent man, – the most eloquent Nova Scotian that ever adorned our Province, – the late Joseph Howe. (Cheers.) I am able to relieve myself of criticism upon that point by stating that he was the first man whose assistance I sought. Although he had been defeated, and was not then in the Legislature of his country, I recognized him as a great leader, a man of great ability, whatever position he might […] I invited him frankly to come …and join hands, as had been done by the statesmen of the older Provinces of Canada, in relation to that great measure.

Unfortunately, I believe for Nova Scotia, Mr. Howe did not concur in the scheme we had propounded and the views we had adopted, and, as you know, when he differed he differed with his whole might. And he became the great leader of the great and powerful party – too great and powerful for us to cope with for a good while – in the Province of Nova Scotia.

I had the good fortune, however, to secure the able and ready cooperation of my friend and old political opponent, the leader of the Opposition in the Province of Nova Scotia, he present Lieutenant-Governor, Hon. Mr. Archibald (Cheers.). From the hour that he joined hands with me, and came to the conclusion, in common with myself, that the common interest of the country demanded that we should unite in endeavouring to promote the welfare of the country – from that hour he was my steady, unwavering, uncompromising supporter. I am glad to be able to bear testimony, not only to the ability and zeal with which he labored in conjunction with the late Judge McCully, but I am happy also to bear evidence to the fact that in the high position of the Governorship of this country, – a position that he now fills and has filled with great acceptance, he has discharged with most signal ability and fairness the duties of a constitutional Governor. (Cheers.)

As I said before we met with a check in the measure of confederation, but were at last enabled by the changed opinion of the members of the House to carry the measure, and I am glad to be able to stand here and feel that notwithstanding all the opposition that was encountered, the time came when even Mr. Howe felt that it was his duty as a statesman and patriot to change the attitude which he had assumed, and take hold of a measure to assist in working out the constitution in the interests of our common country. It has been said that the seductive powers which I exercised were too much for that eminent man, and that on the occasion of my visit to London he was induced to desert the party to which he had committed himself. I have no hesitation in saying to you in all candor that a more unfounded statement was never made. The Hon. Sir A.T. Galt declined to go to England on the ground that the antagonism between Mr. Howe and myself would be fatal to the accomplishment of any good.

The Legislature of Nova Scotia had sent a delegation with Mr. Howe at its head for the purpose of endeavouring to break up the Union. I need not remind you that when I went over in 1866 Mr. Howe addressed a pamphlet of such signal ability to every member of the House of Commons and the House of Lords as to excite great alarm on the part of the friends of Confederation. Lord Carnarvon sent for me and told me of the great impression produced by the pamphlet and asked me to address myself at once to giving it an answer. I did so to the best of my ability, and I am happy to say that it relieved a good deal of the anxiety that had been felt in consequence of Mr. Howe’s publication.

When in 1868 he was sent back to London to get a royal commission to inquire into the working of Confederation with a view to breaking up the Union if he could, I was delegated by the government of Canada to go there for the purpose of giving information to the Imperial Government, and in so far as possible to prevent any damage being inflicted upon the interests of the Union by Mr. Howe. The first thing I did on my arrival was to leave my card for the Hon. Joseph Howe. The next morning he walked into my parlor at the Westminster Palace Hotel and greeted me with the remark that he could not say he was glad to see me but said he “you are here, and I suppose we must make the best of it.”

We sat down and discussed the question as it was worthy of being discussed by two men representing conscientiously what they believed to be the best interests of the country, but holding diametrically opposite views of the situation. I can say that if every word said between us on that, or on any other occasion, was published in tomorrow morning’s newspapers, you would not find a word reflecting upon the honor, character, or integrity of the Hon. Joseph Howe or myself. (Great cheering.) He felt, as no man could fail to feel, the momentous importance of the occasion.

I said to him at once, “You have come here on a mission with a view of obstructing Confederation, and I know too well that you will do all that man can do to accomplish the object for which you are sent here. But I said you will be defeated. An overwhelming majority of the Commons, and a still larger majority of the Lords, will negative your proposal. You will be defeated, and nothing will be accomplished by your mission. The time will come when you will have to face the question what policy you are going to pursue that is not going to be fatal to the Province of Nova Scotia in which you feel so strong an interest. And when that time comes you will find that the conviction will force itself upon you that the only thing you can do, entrusted with the confidence of the people of Nova Scotia as you have been, will be to devote your great talents in assisting to work out a scheme that will exist in spite of you, and to work it out in a way that will be most beneficial to Nova Scotia, – or if you prefer to say it, – in a way that will be least injurious to the people of your country.”

“When that time comes, as come it will, and when you give your great talents to assist the government of this country representing as you do a great majority of the people of Nova Scotia; for you will remember that after a hard and bitter struggle I succeeded in getting back to Parliament without one supporter on the right or left, and a united phalanx supporting Mr. Howe – under these circumstances said I with the extreme responsibility which the confidence of the country has thrust upon your, every hour’s reflection will force you to the conclusion that there is no course open to you but to come forward with the weight of power and influence of the united representation of the Province of Nova Scotia, to assist in working out these institutions in such a way as to make the best of them.”

I knew the man; I knew his patriotic sentiments. I knew him too well not to know that when the time came when it was clear that his hostility would do nothing but injure his country, he would sacrifice himself, if need be, rather than do anything to prejudice the interests of the Province. (Cheers.)

A paper that ought to be a very high authority has recently declared that I am a very mercenary politician; that I am carried away by an insane ambition to secure position for myself, and worst of all money for myself. I do not think my past history warrants that statement. When I first entered public life I sacrificed as independent a position as any man in Nova Scotia could desire to hold. I had a profession of which I was proud, and a large and lucrative practice. I had every comfort that my interests and those of my family required, but I did not hesitate when I felt it was for the good of my country to forego all that and to commit myself as I have already said, to the uncertain sea of politics. Again, when Confederation was carried, I had an official and professional income greater than the amount then enjoyed by the Premier of Canada. So far as mercenary considerations were concerned, I would have looked to my own interests by refusing to enter public life.

When the first Administration of Canada was formed by Sir John A. Macdonald, my hon. friend beside me knows what difficulties had to be encountered in the formation of that Government. These difficulties were solved by myself. It was not a Conservative Administration. It was a combination of the two great political parties, and I said to Sir John Macdonald the solution of your difficulties is for me to withdraw any claim to the position you have afforded me, and to ask my hon. friend D’Arcy McGee to do the same, and I will make room for an Irish Roman Catholic of this Province. Mr. Kenny, now Sir Edward, took my place, and I do not think that action stamped me as a very mercenary or an overambitious politician. I was only too proud to be able to solve the difficulty in that way, and to go back and fight single handed for my country, content if I could obtain an honourable position as a representative of my country in the Parliament of United Canada, there to assist these gentlemen in working out the constitution and carrying forward the great measures devised in the interests of the country.

Well gentlemen, when Mr. Archibald was defeated who was then Secretary of State, and Mr. Kenny was left without a colleague, my hon. friend Sir Alexander knows that I was in a position being the leader of a party, a very consolidated party at that time, a part of one, – that I was quite entitled to become a colleague of Mr. Kenny at the Council Board. But I believed there was a greater and more important service that I could render to the Union, and I asked Sir John A. Macdonald to retain the vacancy thus made by the resignation of Mr. Archibald as Secretary of State until the men whom Nova Scotia had elected and given her confidence to, should select a man to fill the position.

I told Mr. Howe that when the hour should come in which he would feel compelled – as I felt assured the hour would come – to give his services to the assistance of the united government, he would find me just as devoted a supported as he had found me a vigorous opponent. I said I would be content to remain in private life for ever if the result would be to obtain peace and satisfaction in our country and to unite all parties in working out this great question of the confederation of Canada.

As you know, the time did come when Mr. Howe accepted the position of President of the Council, and came to the county of Hants for re-election, and there is nothing in my public life of which I feel prouder in looking back over a long retrospect of twenty-eight years than when nine hundred of the stalwart Conservative yeomanry of that county who had spent their lives in opposing Joseph Howe went up to poll their votes in his support as President of the Council. (Cheers.)

And I may say more, – because you see that I am in a communicative mood tonight and disposed to let you into the secrets of the past. I went to see Mr. Howe the day before the election, when he was shattered by severe illness and dismayed by the hostility of very many old friends. I found him very much broken and apprehensive of the result. I said, “Mr. Howe, you are mistaken, you are not going to be defeated; you are going to be elected. But I tell you this: suppose you should be defeated, don’t do anything rash. Do not resign. I have arranged with my old colleague, Mr. MacFarlane, that if you are defeated in the county of Hants I will resign my seat the next day and you shall be returned for Cumberland by acclamation. (Cheers.) He said, “of course that is impossible, I could not do that.” I said, “you can, because I will tell you what I will do. Mr. Pineo is as much alone in the Local House as I am in the House of Commons of Canada. He will resign and I will go back into the Local House, and see if I cannot straighten matters out there a little.” (Cheers.) I think you will agree with me that Mr. Howe could have had no more faithful supporter than I was on that occasion.

The time came eventually when the appointment of Sir Edward Kenny as Administrator of the government, made a vacancy again in the cabinet, and I was invited to become the colleague of Joseph Howe. And I will say this, having sat at that Council Board, that although we had differed strongly in former years, no two men ever acted with more hearty, cordial, and friendly cooperation in everything designed to promote the welfare and prosperity of the country than Mr. Howe and myself.

When a vacancy afterwards occurred in the office of Lieutenant Governor Mr. Howe was feeble and broken in health. I had an impression that he had long looked upon the highest object of his ambition as being the Lieutenant Governorship of this Province. When Sir John asked me what was to be done in respect to this office, I said “I am going to ask you to tender that office to the Hon. Joseph Howe. I am in hopes that the air of his native Province will restore his health which is a good deal shattered, as you know, and I believe it will be gratifying to himself.” My colleagues were only too happy to adopt the suggestion, and no one lamented more deeply than I did the brief tenure that he enjoyed of that elevated and dignified position.

Upon the death of Mr. Howe the office was tendered to Judge Johnstone who had then retired from the Bench, and was in the south of England for his health, we would then have had in this country the remarkable occurrence of having two Lieutenant Governors in succession who had been for twenty years in the bitterest possible antagonism; and I claim as one of the results of the union of the provinces. It is with no small measure of pride and gratification that I refer to the past, that having gone forward in relation to these great questions with all the vigor and ability that God has given me, faithfully fearlessly and energetically, carrying out what I believed the best interests of the country demanded, it is with no little pride and gratification that I refer to the fact that almost every man who occupied a prominent position in the great Liberal party of Nova Scotia in this province, almost every man has become my political and personal friend.

The hon. William Annand now, now in London, is, I think, the solitary exception, and I believe that a very friendly feeling exists between us at the present moment. As I have said, with reference to the others, the time came when every man of mark, every leading man of the Liberal party, was in perfect accord of opinion with myself. It is no small source of pleasure, and it is one of the evidences of the effect of what Confederation has done for this country in elevating us out of that small groove, that narrow and bitter antagonism which formerly prevailed.

I spoke a moment ago of the Conservative party and of my having been the leader of the Conservative party. I was mistaken. From that hour when the public men of this country joined hands on that great question and were found upon the same side, it became the great Liberal Conservative party, and it is the Liberal Conservative party today, because, while Conservative in the highest and best sense of the word, and especially in that most important of all senses, of maintaining in an undeviating and unflinching manner the connection between these Provinces and the British Crown, (Cheers.) there is no measure of reform, nothing for the extension of popular control, no measure to give scope and field to the various populations now flowing into the country, no measure that the best interests of the masses demand at the hands of the government, that this Liberal-Conservative party have not grappled with and carried to a successful issue.