This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By Charles Burton, August 28, 2023

As China’s economy tanks in dramatic fashion, there are growing signs that it is scrambling to avoid any civil unrest fanned by the downturn.

Earlier this month, after seven consecutive months of rising youth unemployment, Beijing announced it will stop releasing jobless statistics for young people. Official figures put unemployment among 16- to 24-year-olds in urban areas at 21.3 per cent; objective observers suspect it is much higher than that.

But leaders are concerned by more than the spectre of frustrated urban youth staging public demonstrations against the Chinese Communist Party. Another time bomb is the disintegration of China’s housing and real estate sector in medium and small cities, where a growing number of people have prepaid for apartments that may never get built.

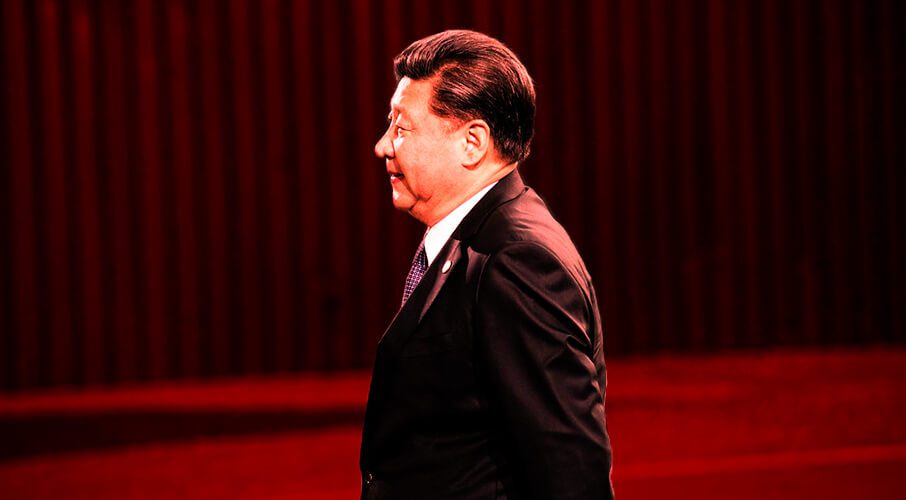

Developments like these, combined with a steep drop in foreign investment, are diminishing Xi Jinping’s charisma as China’s wisest steward (as per his own philosophical essay, Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era). It seems his Stalinist bent for economic policies – favouring state control over private enterprise, underhanded bad-faith dealings in international trade, and economic coercion – isn’t working as expected. China seemed stunned this year when the U.S. responded to Mr. Xi’s new economic gospel by imposing tariffs on a wide range of Chinese imports, and cracking down on China’s covert acquisition of U.S. technologies with military applications.

More significantly, the end of the economic boom threatens China’s “post-Tiananmen bargain” in which citizens tolerate marginalized civic freedoms and rule of law in return for continuously improving living standards. Suddenly, Mr. Xi seems politically vulnerable. His rule has been markedly more repressive than those of his recent predecessors – reversing Deng Xiaoping’s 1980s initiatives of “opening and reform” and exhortations to “liberate thought” against Maoist dogma – and because Mr. Xi has purged all his political rivals over the past 10 years, when things go wrong in this era, the buck stops with him.

Mr. Xi’s rap sheet includes the COVID-19 fiasco, wherein Communist officials, desperate to protect themselves from public scorn, lied about the cause and human-to-human transmission of the virus, thereby endangering the health of ordinary citizens. This was followed by Beijing’s abrupt reversal of its draconian “zero-COVID” quarantine policies, leading to massive outbreaks of illness and death.

Everybody in China knows that the Party’s statistics about COVID deaths, and its propaganda about the 180-degree policy shift, were false; the day-to-day reality confronting people all across the country bore no resemblance to what was being reported by state media. Mr. Xi lied to the people. The people know he lied to them.

The impression of Xi Jinping being firmly in command of the Communist Party is also being blurred by signs of discontent within China’s military leadership. This month, it emerged that Mr. Xi dismissed two generals commanding China’s Rocket Force nuclear arsenal, Li Yuchao and Xu Zhongbo; neither has been seen since. Mr. Li’s deputy Liu Guangbin has also disappeared, along with former deputy Zhang Zhenzhong. And Wu Guohua, deputy commander of the Rocket Force, reportedly committed suicide in July.

Several weeks ago, foreign minister and influential policy maker Qin Gang suddenly disappeared and was removed from his post without explanation. Speculation has been furious. As a barometer of China’s stability, veteran China-watchers say that in this environment, any sudden changes of senior officials are seen as signs of weakness, instability or opposition to Mr. Xi’s regime by Communist insiders.

If Mr. Xi has indeed compromised in his ability to weather political damage because of his handling of the economy, his mishandling of COVID, or sudden disappearances of his senior officials, then these will only add to longer-term grievances that have quietly accumulated during his rule: the persecution of #MeToo protesters, China’s growing income gap, the economic privileging of “red nobility” elites, the unfair and corrupt legal system, pervasive state surveillance and strict censorship of social media.

Against this backdrop, unemployed youth who feel resentful and badly done by could, as Chairman Mao put it in quite a different context, be the spark that sets off the prairie fire. There is much precedent for this in Chinese history.

Charles Burton is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, non-resident senior fellow of the European Values Center for Security Policy in Prague, and a former diplomat at Canada’s embassy in Beijing.