There is nothing sacrosanct about the guarantees of central bank independence. It is not written in any constitution. The political system that granted this independence can also take it away, writes Philip Cross.

There is nothing sacrosanct about the guarantees of central bank independence. It is not written in any constitution. The political system that granted this independence can also take it away, writes Philip Cross.

By Philip Cross, January 10, 2018

The sniping at Bank of England Governor Mark Carney from the U.K.’s Tory backbenchers over his fearmongering about the perils of Brexit and President Donald Trump’s threat to replace Jerome Powell as chair of the Federal Reserve Board for raising interest rates have both renewed concerns about preserving the independence of central banks from political influence. Of course, central bank independence would not be necessary if monetary policy were guided by mechanical rules and fixed formulas instead of the discretion currently exercised by central bankers. But rules have been out of favour since the early 1980s when they were revived to stop political meddling and decisively brake inflation.

Trump is hardly the first American president to pressure the Fed to lower interest rates, a time-honoured practice used by presidents Truman, Johnson and Nixon. Ongoing political pressure for easy money helped fuel rampant inflation in the 1970s. The move in the 1980s and 1990s to insulate central banks from politics was one of many responses deployed to fight inflation. Central bank independence eventually gained widespread acceptance among parties of all stripes, partly because independence by itself helps lower inflationary expectations and, therefore, interest rates.

However, there is nothing sacrosanct about the guarantees of central bank independence. It is not written in any constitution. The political system that granted this independence can also take it away. This is especially the case if central banks fail to deliver the financial stability, low inflation and improved economic performance that were the promised benefits of their independence.

Since gaining independence, the track record of central banks has been uneven at best. While consumer price inflation has stayed low, central banks have encouraged “rational bubble riding” in financial and housing markets going back to the late 1990s. The serial stoking of asset-price inflation by central banks whose independence was premised on low inflation and financial stability recalls former Norway Bank Governor Hermod Skånland’s observation in 1988, on the effect of soaring oil prices, that “We carefully plotted a course and then immediately headed in a different direction.”

A corollary of central bankers being free from political interference is that central bankers also must refrain from involvement in political debates. After all, if central banks expect to be insulated from politics, they cannot willingly enter the political arena without expecting consequences. In his recent book about central banking, Unelected Power, Paul Tucker, a former deputy governor of the Bank of England, points out that if banks want independence, “reciprocally, they should not participate in party politics, even in the private recesses of their minds.”

On this score, they have failed miserably. Central bankers in recent years have routinely intruded into politics. Most notably, Carney, while governor of the Bank of Canada, dabbled with the idea of running for the leadership of the federal Liberal party. He further revealed political biases in public pronouncements on everything from the voluntary long-form census to the risks of climate change (both subjects important to the left-wing circles Carney seeks to command).

The European Central Bank, considered by many to be the least politically accountable central bank in the world, urged Spain and Italy in 2011 not just to lower their deficits but specified that they must do so using spending cuts and tax hikes. It even quietly encouraged Italy to invoke Article 77 of its constitution to ram through emergency measures (ignoring the criticism from Italian courts of the article’s overuse). Italy’s then-prime minister Silvio Berlusconi accepted the terms but later said the ECB’s instructions “made us look like an occupied government.”

And Alan Greenspan, when he was U.S. Fed chairman, openly lobbied the Clinton administration to cut the federal budget deficit, demonstrating how the tables had turned from the days when presidents were the ones pressuring the Fed, to the point where the Fed was dictating policy to presidents. Today, the extraordinary policies of zero or even negative interest rates and quantitative easing clearly have large political and distributional impacts, yet these policies were adopted with almost none of the public debate that would have buttressed their legitimacy.

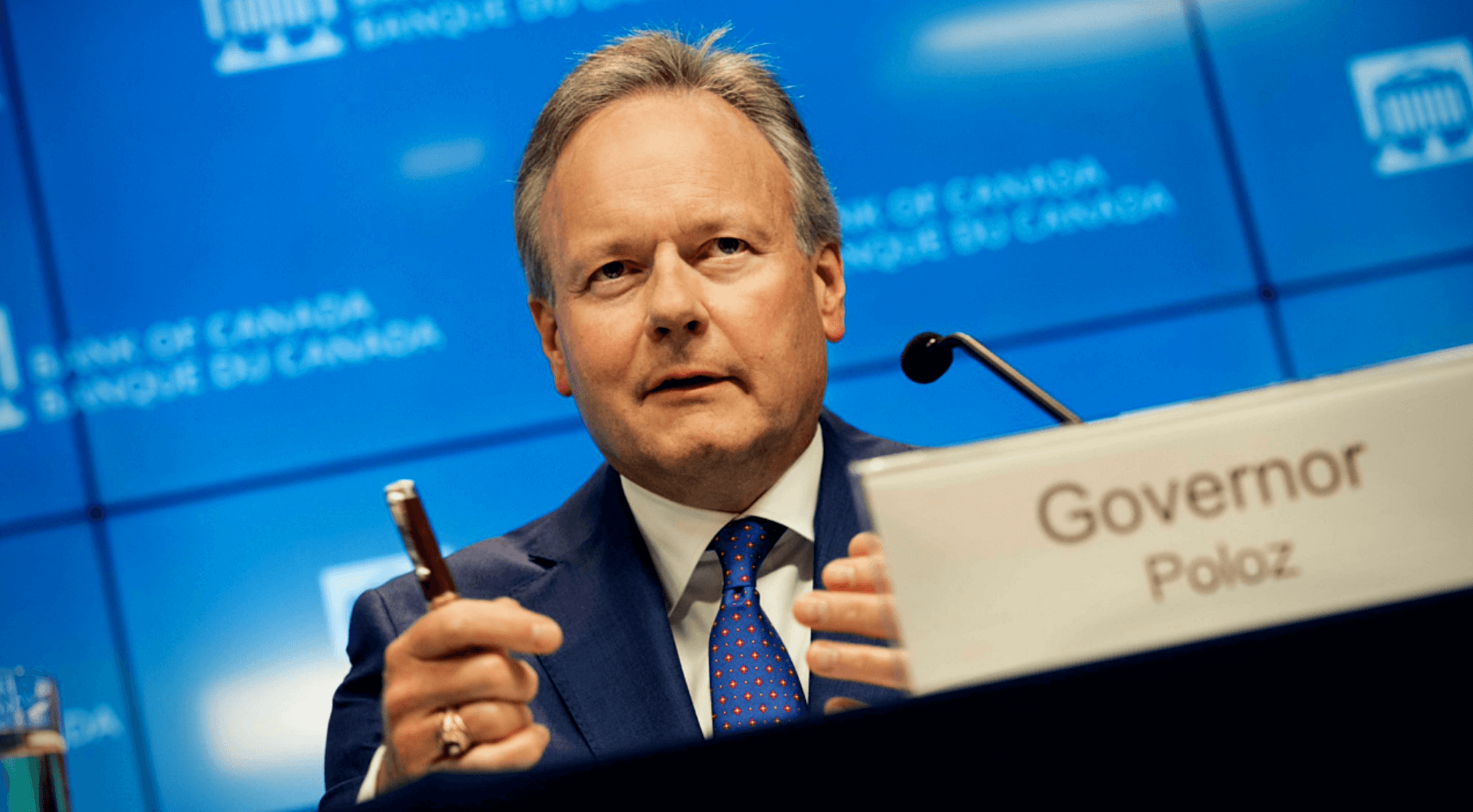

Central bankers made their job harder by welcoming the media’s cult of celebrity (note the contrasting demeanour between Carney’s preening style as Bank of Canada governor and the modesty of his successor, Stephen Poloz). It began with Greenspan in the 1990s — even though Greenspan’s “maestro” reputation lies in tatters today. Next, Fed chairman Ben Bernanke was credited with staving off a depression during the global financial crisis, although the crisis itself revealed systemic problems with both the Fed’s bank supervision and persistently low interest rates. The ECB’s Mario Draghi was hailed as the saviour of the euro after his 2012 promise to do “whatever it takes” to preserve the currency, but the euro’s future nevertheless remains dubious.

By accepting accolades that they are the infallible high priests of global monetary activism, central bankers invite the public to hold them to impossibly high standards. When they fail to live up to those standards, as they often do, they can only invite questions about whether they deserve the independence they demand.

Malaysia’s former central bank governor, Jaffar Hussein, once said “Good bankers, like good tea, are best appreciated when they are in hot water.” Today, the water temperature surrounding central banks continues to rise rapidly. If public suspicions are confirmed that the lengthy recent stretch of ultra-low interest rates and quantitative easing have only set the stage for rising debt and serious inflation, it would seem inevitable and justifiable that politicians will demand more direct input into monetary policy.

More than independence is at stake. Central bankers risk losing credibility in claiming that exercising their discretionary judgement is superior to the centuries-old wisdom that governments will always try inflating away large debt loads unless they’re checked by hard-and-fast rules governing money. Their curtain will have been pulled back, revealing the banking wizards frantically fidgeting with the dials on debt and inflation time bombs.

Philip Cross is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.