MLI’s Annual Foreign Policy and International Affairs Survey reveals both opportunities and challenges for policy-makers who are tasked with securing Canada’s interests on the global stage. The full poll results are available to read and download here. A selection of key data is available to explore in the interactive module immediately below, and you can read the full analysis further down the page or here. MLI also hosted a webinar discussion breaking down some of the survey’s findings which can be watched in full here.

Foreign policy received little attention from Canada’s political leaders in the 2021 federal election. While such an oversight may be predictable, it is also unfortunate – as the very future of our country is being shaped and defined by foreign affairs. To help correct this oversight, MLI conducted opinion polling, in tandem with the Konrad-Adenaeur-Stiftung, to ascertain the views of Canadians on the most important issues facing our country beyond our borders.

The polling, done on an annual basis, builds off the results from 2020 and reveals some changes in Canadians’ attitudes and opinions on matters of foreign policy and international affairs.

Overall knowledge of foreign affairs declined in 2021. While this may be attributable to screening questions used to ascertain International Knowledge Scores (IKS) in this most recent survey, it correlates predictably to weaker views on foreign policy more generally, and views that tend to see our allies with more skepticism, our adversaries with more acceptance, and our important international partnerships with greater negativity.

Despite growing public interest in our country’s place on the world stage, Canadians appear to be less certain about the states who share our interests and the states who oppose them. Between our political leaders, media, academia, and civil society, there is a need and appetite for greater public education and debate on foreign affairs.

While this information can help inform policy-makers, Canada’s actions on the global stage need to be driven by our interests and values. Where interests are aligned with public opinion, this task is easy. Where interests and public opinion diverge, this task is more challenging. This polling should help identify easy wins for Ottawa, and areas where the government’s direction and our public debate make Canada more effective internationally – in cooperation with allies or in competition with adversaries.

Canada’s role in the world

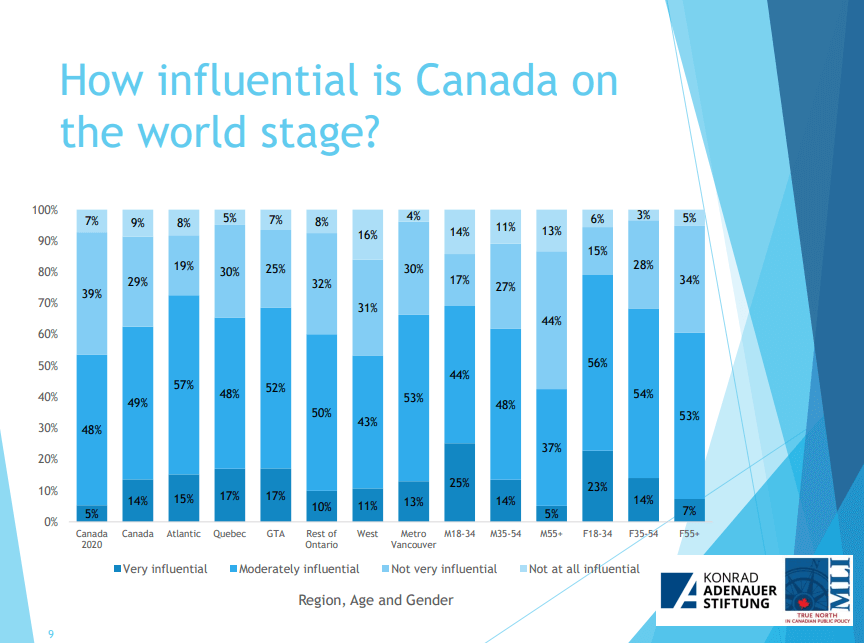

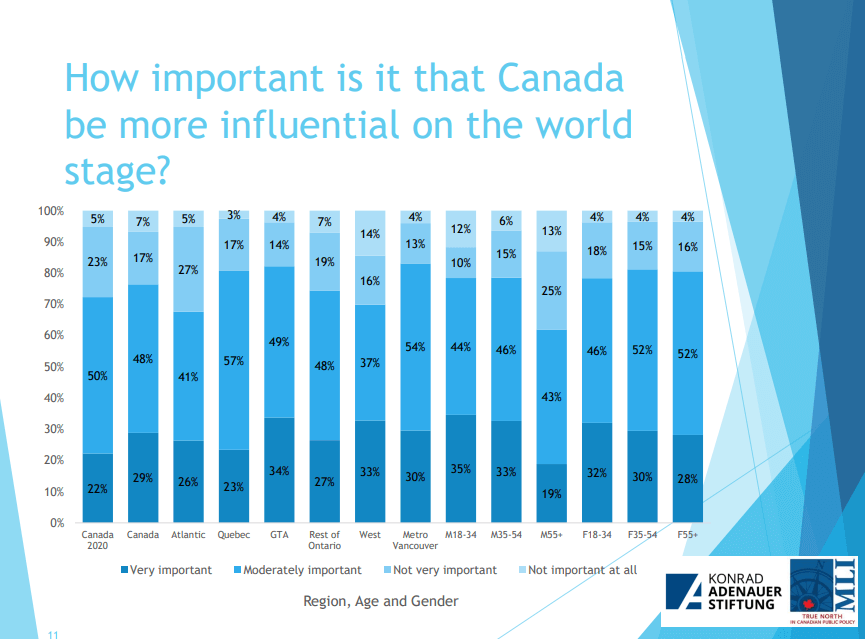

Looking at the data, 63 percent of Canadians say our country is very or moderately influential on the world stage, an increase of 10 percent since 2020. Over three-quarters (77 percent) of Canadians believe it is important for Canada to be influential on the world stage, an increase of 5 percent since 2020. It is not clear why more Canadians think our country is more influential at the world stage as there are no clear, discrete sets of events that demonstrate increasing international clout for Canada. In fact, Canada has conversely been viewed by many key partners and allies as less influential. This is true especially in groups such as the Five Eyes intelligence grouping. It is possible 2020 might be a low point in Canadian public opinion regarding our country’s influence in the world and we have returned to a more optimistic baseline. This interpretation has partial support from the fact more Canadians are optimistic about the future compared to last year, as discussed later in this report.

Looking at the data, 63 percent of Canadians say our country is very or moderately influential on the world stage, an increase of 10 percent since 2020. Over three-quarters (77 percent) of Canadians believe it is important for Canada to be influential on the world stage, an increase of 5 percent since 2020. It is not clear why more Canadians think our country is more influential at the world stage as there are no clear, discrete sets of events that demonstrate increasing international clout for Canada. In fact, Canada has conversely been viewed by many key partners and allies as less influential. This is true especially in groups such as the Five Eyes intelligence grouping. It is possible 2020 might be a low point in Canadian public opinion regarding our country’s influence in the world and we have returned to a more optimistic baseline. This interpretation has partial support from the fact more Canadians are optimistic about the future compared to last year, as discussed later in this report.

“Canadians are growing more confident in realizing our influence, and that bodes well,” says Shuvaloy Majumdar, MLI Munk Senior Fellow and Foreign Policy Program Director. “This data should serve as a reminder that an activist foreign policy, one where Canada embraces its leadership potential, is attainable and desirable in the eyes of Canadians.”

“Canadians are growing more confident in realizing our influence, and that bodes well,” says Shuvaloy Majumdar, MLI Munk Senior Fellow and Foreign Policy Program Director. “This data should serve as a reminder that an activist foreign policy, one where Canada embraces its leadership potential, is attainable and desirable in the eyes of Canadians.”

Views of countries: Partners, democracies, and like-minded countries

With President Biden replacing President Trump, Canadians’ views toward the US have markedly improved, moving from a net-negative of -44 percent to a net-positive of +16 percent. This stark and dramatic 60-point swing represents the most significant change measured in this survey.

Beyond a visceral dislike of Trump among Canadians, this also points to another fact: Canadians are saturated with news, opinions, and commentary regarding the United States. This means Canadians are more likely to tie their opinions to the attitudes, policies, and peculiarities of the US government of the day, rather than view the Canada-US relationship on the basis of Canadian priorities with the United States.

Even still, Canadians are not as positive about the United States – a clear and critical ally in terms of security, economic prosperity, and shared values on the global stage – as the relationship between our two countries might suggest. This speaks to another potential quirk of Canadian public opinion revealed in this polling: Canadians appear distrustful of superpowers. In this sense, there is a continuity with the results from last year, namely, middle power weariness toward major power imbalances.

Of all countries measured, Australia is viewed most positively by Canadians (net-positive of 58 percent). This suggests that shared values and history are important factors in shaping Canadian perceptions of countries, and alongside very positive views of the UK and the Five Eyes alliance (discussed below), the Anglosphere continues to be a central feature in how Canadians view the world.

Second to Australia in the Indo-Pacific region, Japan is viewed most positively (net-positive of 45 percent). South Korea is viewed positively as well (net-positive of 23 percent). That said, both Japan and South Korea’s net positivity rates dropped by 8 and 9 points, respectively, since 2020. It is unclear what underpins this change in opinion, even though Canadians continue to hold overwhelmingly positive opinions of both. Opinions of Taiwan remain relatively unchanged since 2020, sitting at a net-positive of 21 percent.

Opinions of other East Asian democracies (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan) increase dramatically as IKS increases. These three countries enjoy a net-positive of roughly 60 percent among those with high IKS, versus a net-positive of 30 percent among Canadians generally. For countries that share Canadian interests, values, and systems of democratic governance, there are significant opportunities to strengthen ties and public perceptions of these alliances in East Asia. “It’s clear that Canadians, regardless of their educational background, recognize East Asia’s key democracies as the most favourable and aligned with our interests,” according to Jonathan Berkshire Miller, MLI Senior Fellow and Indo-Pacific Director.

In Europe, the United Kingdom is viewed most positively (net positive of 52 percent) among countries measured, which is relatively unchanged from 2020. Germany also enjoys a high net-positivity score of 47 percent. This is a drop of 10 points from 2020, driven largely by an increase in neutral opinions, reflecting again a drop in knowledge about foreign affairs more broadly. It is unclear if Germany’s election had any bearing on this result.

Canadian opinions toward Latvia have doubled, from 3 percent net-positive in 2020 to 7 percent net-positive in 2021. Canadians may be more aware of Canadian leadership in NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) mission in Latvia, as neutral opinions have decreased by 8 percent since 2020.

Opinions toward Ukraine shifted significantly from a net-negative of -8 percent in 2020 to a net-positive of 9 percent in 2021. Positive views of Ukraine are most common in Western Canada. It is unclear whether the subject of Ukraine and Russia as they pertain to controversies over the US election, or Ukraine’s resistance against Russian encroachment generally, have shifted public opinion. However, while opinions have shifted, 55 percent of Canadians have a neutral opinion of Ukraine.

Some democracies that share long-standing interests with Canada are viewed with skepticism by Canadians, particularly Israel and India. Notably, these countries exist in dangerous geographies, directly bordered by actors conducting irregular warfare and terrorism. Israel and India are outliers among the democratic cohort, with net ratings of +2 percent and -7 percent, respectively. Canadian leaders will need to contend with public opinion as they seek to develop these critical relationships.

Perceptions of Israel improved significantly since 2020, growing 15 points. This growth is clear in a variety of cohorts, but most significantly among those with high IKS. As Israel’s 2021 election was an IKS screening question, it is most likely the case that the change in Israel’s government is a significant factor in this change in opinion. Even still, 2021 saw a significant flare up in the conflict between Israel and the terrorist organization Hamas, which operates principally in Gaza. It cannot be discounted that the shift in Canadians’ opinion was connected to sympathy for Israel in this conflict.

Though still somewhat negative, net-opinions of India improved since 2020, growing 8 points. Opinions of India are particularly positive in Atlantic Canada, with young men and foreign policy voters. Once again, there are few clear events to explain this shift in opinion, though it is notable that MLI’s experts have long articulated that the Canada-India relationship is one of significant opportunity and promise.

According to Miller, “Positive perceptions toward India have grown among Canadians, which is cause for optimism and ambition.

“India is the world’s largest democracy and a critical and fast-growing economy. It also shares many of our interests for a rules-based international order. Increasingly, India is playing an active and constructive role in the security of the Indo-Pacific region. Our countries have much to benefit from one another, and increased federal ambition to that end should be strongly supported.”

Results from the US indicate that Canadians appear to attach perceptions of certain countries to perceptions of their leadership or government. While not unreasonable, there is a need for a better understanding of the differences between a state and its government. This is particularly true when it concerns Canada’s central foreign and security relationship.

“The fact is, whether it is Trump or Biden in the White House, 75 percent of our trade is directly tied to the US. And whether Democrats or Republicans hold the upper hand in Congress or across state capitals, Canada’s fundamental defence and security interests are inseparable from our relationship with the United States,” says Majumdar. “While it is productive that Canadians’ opinions of the US have improved, we should expect the media and government to do a better job in going beyond mere partisan flattery, beyond adopting challenges in American democracy as immediately transcribable to Canadian democracy, to instead feature real and strategic priorities between our two countries.”

Views of countries: Authoritarian and disruptive regimes

Canadians remain largely clear-eyed in their assessment that authoritarian and disruptive regimes stand opposed to Canada’s interests. Regimes that are authoritarian or undermine the rules-based international order are viewed far more negatively (net-negative -37 percent) on average than more like-minded democracies (net-positive of roughly 25 percent). Those with the greatest knowledge of international affairs have the most negative and pronounced views of authoritarian/disruptive regimes.

This is most clear with China, which is the country viewed most negatively (net-negative -47 percent) in our survey.

A clear majority of Canadians (62 percent) maintain a negative view of China, which has softened 11 points from 73 percent measured in 2020. Only 15 percent of Canadians hold a moderately positive view of China, with 23 percent neutral. Those with high IKS view China most negatively (85 percent), suggesting that as knowledge about China’s actions increases, so too do negative views of the country.

With the release of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, opinions of China may have softened. Additionally, as the origin story of COVID-19 recedes from public debate, it is likely that the focus of Canadians has shifted from initial responsibility for the pandemic to other issues.

“Canadians remain resolute in their skepticism on China and its increasingly assertive policies in the Indo-Pacific region and globally,” says Miller. “More work will need to be done to articulate that the challenge of dealing with Chinese actions are strategic in nature. We must resist the temptation to get stuck on ‘episodes’ that appear tactical and isolated, but are in fact interrelated and persistent. A long-term strategic lens – one done in tandem with our key Indo-Pacific allies – is needed.”

Canadian views on Russia also softened in 2021, moving from a net-negative score of -64 percent in 2020 to a net-negative score of -31 percent in 2021. Even still, 49 percent of Canadians view Russia at least somewhat negatively in contrast to only 18 percent who have an even modestly positive view of Russia. The largest change from 2020 appears to be a move from negative to neutral opinions; the size of the negative cohort shrank from nearly three-quarters to one-half of Canadians, whereas the share of neutral Canadians grew from less than a quarter to now more than a third of Canadians.

In any case, softening opinions on Russia do not appear to be directly tied to any specific event, and indeed, appear to be inconsistent with Russia’s increasingly bellicose activities during the survey period. Once again, lower information appears to correlate to less negative opinions about Russia.

New to this round of polling were questions about Canadians’ views of Pakistan, which like other disruptive regimes was viewed overwhelmingly negatively by Canadians. Pakistan has a net score of -33 percent, the second worst of any country measured. Only 13 percent of Canadians have an even moderately positive view of Pakistan.

Negative views regarding Pakistan are consistent with one of the most important news stories of 2021: the fall of democratic Afghanistan to the Pakistan-backed Taliban. This suggests Canadians support a policy that holds Pakistan accountable as a rival.

“It is possible, though hard to prove, that a growing presence of disinformation is muddling public opinion about regimes that do not share our interests,” says MLI Senior Fellow Marcus Kolga. “This would be consistent with repeated warnings from Canadian intelligence agencies, as well among as the growing number of voices in Canadian civil society.”

Delving more deeply into the determinants of why Canadian attitudes have shifted regarding authoritarian regimes is critical to defending Canadian values and interests. It is especially so as these regimes intensify their assaults against democracies worldwide.

Threats to Canada

Of all state-based threats to Canada, China is seen as the most serious threat. That being said, only 36 percent see China as a serious threat, down from 44 percent in 2020. Sixty-nine percent of Canadians believe that China is either a moderate or serious threat, and only 21 percent of people see China as a small threat or no threat at all. Canadians’ perception of the threat posed by China grows as IKS increases. Young women and residents in Atlantic Canada are the least likely to perceive China as a threat, and immigrants to Canada and those who voted Liberal are more likely to see China as a moderate rather than serious threat.

Since 2020, Canadian perceptions of the risk posed by Russia have also dropped. Now, one in five Canadians believe Russia poses a serious threat to Canada, down 8 percent. Of those surveyed, 56 percent believe Russia poses at least a moderate threat to Canada, with the remaining 44 percent responding that Russia is either a small threat (27 percent) or no threat at all (17 percent). Young women, those with low IKS, and those for whom foreign policy is not important are least likely to see Russia as a threat.

As MLI Senior Fellow Balkan Devlen argues, “at a time of rising threats posed by authoritarian regimes, whether it is China toward Taiwan or Russia toward Ukraine and, more recently, the people of Kazakhstan, many Canadians are becoming less concerned and more inward looking.

“If these flashpoints turn hot or if authoritarian aggression spills over so much so that Canada is forced to act in defence of our interests, policy-makers should be aware that there appears to be a growing information gap among some in the Canadian public and that might hamper an effective Canadian response.”

Beyond superpower challenges, 33 percent of Canadians believe Taliban-ruled Afghanistan poses a serious threat to Canada, and an additional 31 percent believe the Taliban pose a moderate threat to Canada. Those most likely to see the Taliban as a moderate or serious threat include French Canadians (69 percent) and Atlantic Canadians (68 percent).

Iran is seen as a serious threat by roughly the same amount as last year (23 percent). Iran is seen as a moderate threat by an additional 34 percent of the population. Older women, Quebeckers, high IKS, and foreign policy voters are all more likely to see Iran as a threat to Canada.

“In 2020, Iran shot down a passenger aircraft with 55 Canadian citizens and 30 permanent residents on board. That clearly suggests the regime poses a clear, obvious, and serious threat to Canadian lives and interests,” says MLI Senior Fellow Kaveh Shahrooz. “While many Canadians intuitively grasp the danger posed by Iran’s regime, more work needs to be done to articulate how Iran’s actions, especially its unwavering state-sponsorship of terrorism, create a less safe world.”

In 2020, fully 61 percent of Canadians believed that the United State posed a serious (26 percent) or moderate (35 percent) threat to Canada. With Trump out of the White House, those numbers have dropped to 12 percent and 22 percent, respectively. Young women, the well-educated, NDP voters, and non-foreign policy voters are more likely to see the US as a serious threat.

Views of international organizations

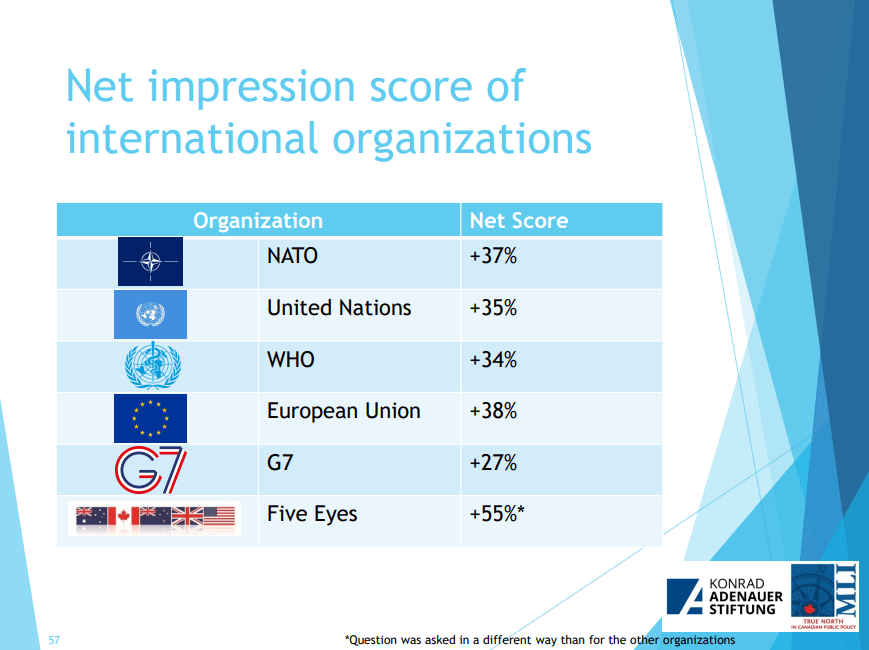

Net impressions of international organizations decreased slightly over 2021, though Canadians remain largely supportive of key international and multilateral bodies. Indeed, the general perspectives of Canadians have changed very little, but there are some notable exceptions. In most cases, high IKS scores are generally correlated with better views of international organizations.

Net impressions of international organizations decreased slightly over 2021, though Canadians remain largely supportive of key international and multilateral bodies. Indeed, the general perspectives of Canadians have changed very little, but there are some notable exceptions. In most cases, high IKS scores are generally correlated with better views of international organizations.

Half of Canadians (50 percent) hold a positive view of NATO, with only 12 percent holding a negative view, with a net-impression of +37 percent – a drop of 8 points since 2020. Canadians are over three-times as likely to be very positive (18 percent) about NATO as they are to be very negative (5 percent). A third of Canadians (33 percent) hold a neutral view, and 6 percent report never having heard of the organization. Young women, the less educated, and those with low IKS are the most likely to have never heard of NATO. People for whom foreign policy is not at all important to their vote are most likely to have a negative opinion of the Alliance (22 percent), but even in this cohort, NATO has a 10-point net positive opinion.

“Canadians generally continue to view international organizations positively, though somewhat less positively than in 2020 in the case of NATO,” says Devlen. “While opinions of NATO remain very positive, this shift should be carefully monitored as NATO plays such a central role in Canada’s foreign policy interests and defence posture.” Further data discussed later in this polling series examines perspectives on NATO more deeply.

Canadians are similarly positive about the United Nations, with a net impression score of +35 percent. Roughly half (52 percent) of Canadians view the UN positively, and 17 percent view it negatively. These numbers are statistically similar to 2020. The UN has one of the starkest partisan divides, with Liberals having very positive views (68 percent) and Conservatives much less so (42 percent). Once again, those for whom foreign policy is not important at all to their vote are the most starkly negative (31 percent).

The World Health Organization (WHO), European Union (EU), G7, and Five Eyes all enjoy similar levels of approval as they did in 2020 among Canadians. The Five Eyes remains the most popular of all these groups, with a +55 percent net impression score, though the question was asked in a different way. Opinions about the Five Eyes track most closely with IKS; while only 47 percent of very low IKS respondents view the organization positively, that number shoots up to 85 percent for high IKS respondents.

According to Miller, “the Five Eyes represents an alliance of both strength and opportunity that would benefit from expanding into other aspects of international relations.” A recent MLI paper by John Hemmings and Peter Varnish argued that the Five Eyes grouping could be used by Canada and others to expand the ability to counter and deter China and Russia across multiple areas, including technology, information, military, and economics.

Views on international affairs

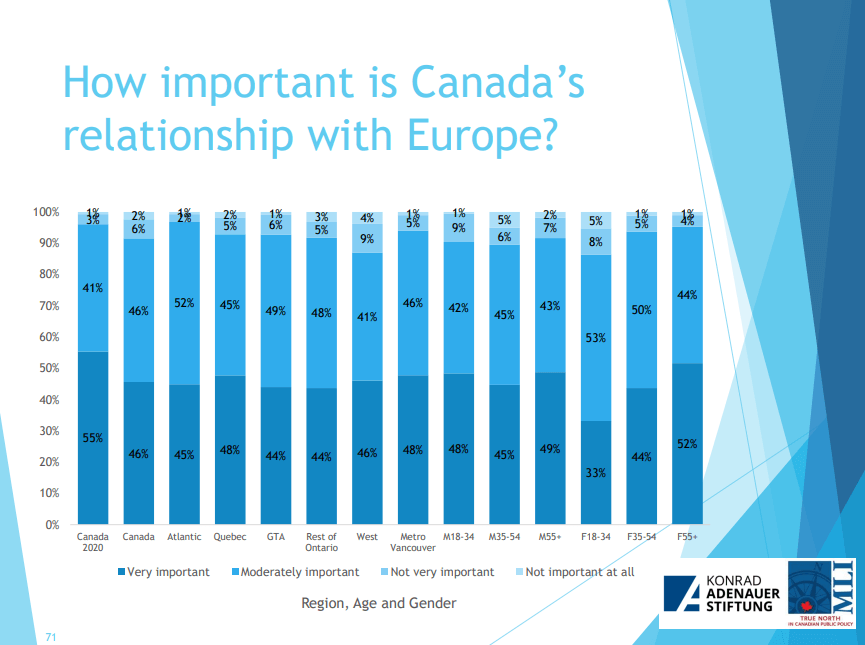

Canadians are nearly universal (92 percent) in believing that Canada’s relationship with Europe is modestly important (46 percent) or very important (46 percent). Though a small, 4-point drop from 2020, the data suggest that greater cooperation and engagement with our European allies would still be viewed positively by Canadians. With so many of Canada’s traditional democratic and likeminded allies in Europe, this positivity comes as no surprise. Canada’s transatlantic role, particularly as it relates to NATO and security, was analysed in MLI’s “Across the Pond” podcast series.

Canadians are nearly universal (92 percent) in believing that Canada’s relationship with Europe is modestly important (46 percent) or very important (46 percent). Though a small, 4-point drop from 2020, the data suggest that greater cooperation and engagement with our European allies would still be viewed positively by Canadians. With so many of Canada’s traditional democratic and likeminded allies in Europe, this positivity comes as no surprise. Canada’s transatlantic role, particularly as it relates to NATO and security, was analysed in MLI’s “Across the Pond” podcast series.

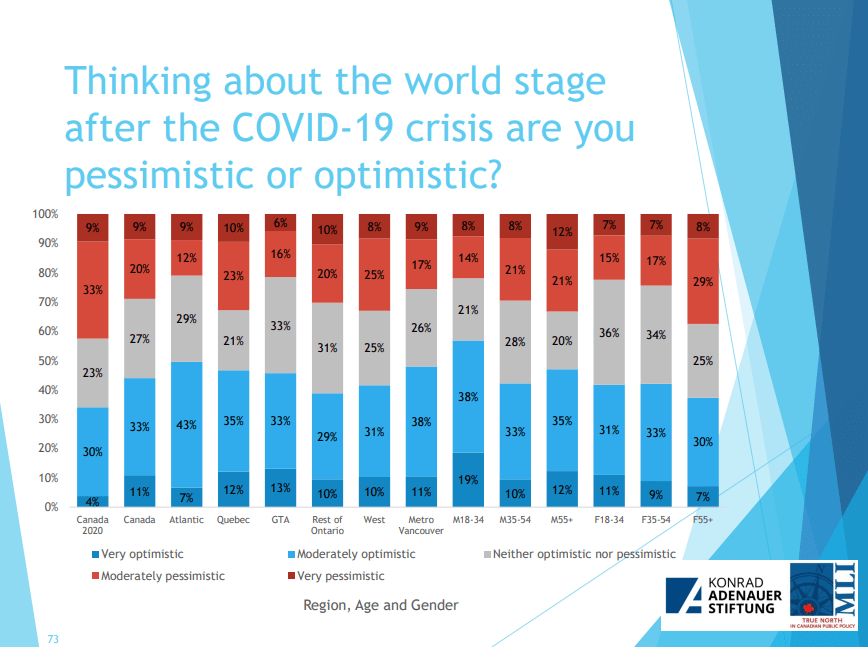

Canadians are more optimistic about the future of the world stage after the COVID-19 pandemic, with a net-positivity of 15 percent (though the survey was done prior to the Omicron wave). This represents a 21-point improvement since 2020. Overall, 44 percent are optimistic and 29 percent are pessimistic, with 27 percent somewhere in between. Atlantic Canadians, young men, high-earners, immigrants, those with high IKS, Liberal voters, and voters most interested in foreign policy have expressed the most optimism.

In Devlen’s view, “as vaccinations blunt the threat posed by COVID-19, it appears that Canadians have become more optimistic about the state of the world. While reintroduced lockdown measures following the Omicron wave are perhaps a reminder that it is too early to break out the bubbly and celebrate the end of the pandemic, it seems that Canadians have regained a positive view of the future.”

In Devlen’s view, “as vaccinations blunt the threat posed by COVID-19, it appears that Canadians have become more optimistic about the state of the world. While reintroduced lockdown measures following the Omicron wave are perhaps a reminder that it is too early to break out the bubbly and celebrate the end of the pandemic, it seems that Canadians have regained a positive view of the future.”

On economic issues, Canadians views on globalization remain largely unchanged from 2020. Canadians are largely positive about globalization (69 percent), but the largest cohort of Canadians believe that it should slow down, despite being positive for the world (48 percent).

“These views speak to an inherent caution in Canadians’ views of the global economic order. Despite unique challenges during the pandemic, particularly challenges which have harmed global supply chains and led to higher inflation than wage growth, few Canadians believe that a radical overhauling of the global economy would be helpful,” argues MLI Domestic Policy Program Director, Aaron Wudrick. “Few seem to think that reverting to autarky or isolation is preferable.

“Canadians appear to recognize that globalization comes with benefits as well as drawbacks. This suggests Canadians are comfortable with maintaining the interconnected global economic system, while still acknowledging the system’s unintended consequences with respect to economic dislocation, climate change, economic coercion, and more challenges that need to be considered and inoculated against.”

Canada’s foreign policy

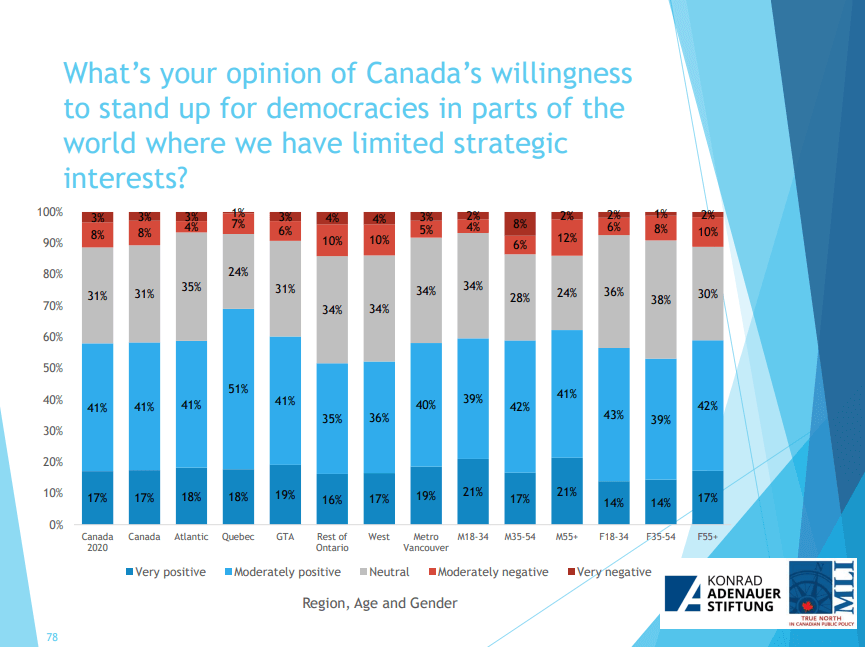

Canadians remain unchanged in their positive view (58 percent) of the country’s willingness to stand up for fellow democracies, even in regions in which we have limited strategic interests. Just 12 percent feel negatively. Additionally, Canadians are more than twice as likely to believe that we should side with other democracies rather than acquiescing to the wishes of multilateral institutions like the UN (54 percent to 23 percent, respectively) This reflects a 4-point shift into the “democratic” rather than “multilateral” camp since 2020.

Canadians remain unchanged in their positive view (58 percent) of the country’s willingness to stand up for fellow democracies, even in regions in which we have limited strategic interests. Just 12 percent feel negatively. Additionally, Canadians are more than twice as likely to believe that we should side with other democracies rather than acquiescing to the wishes of multilateral institutions like the UN (54 percent to 23 percent, respectively) This reflects a 4-point shift into the “democratic” rather than “multilateral” camp since 2020.

“Anchoring our foreign policy among democratic allies remains a clear winning strategy in the eyes of Canadians,” says Majumdar. “Even though doing so may result in disagreement with international bodies, when forced to choose, Canadians are willing to pick our allies over multilateral equivocation.”

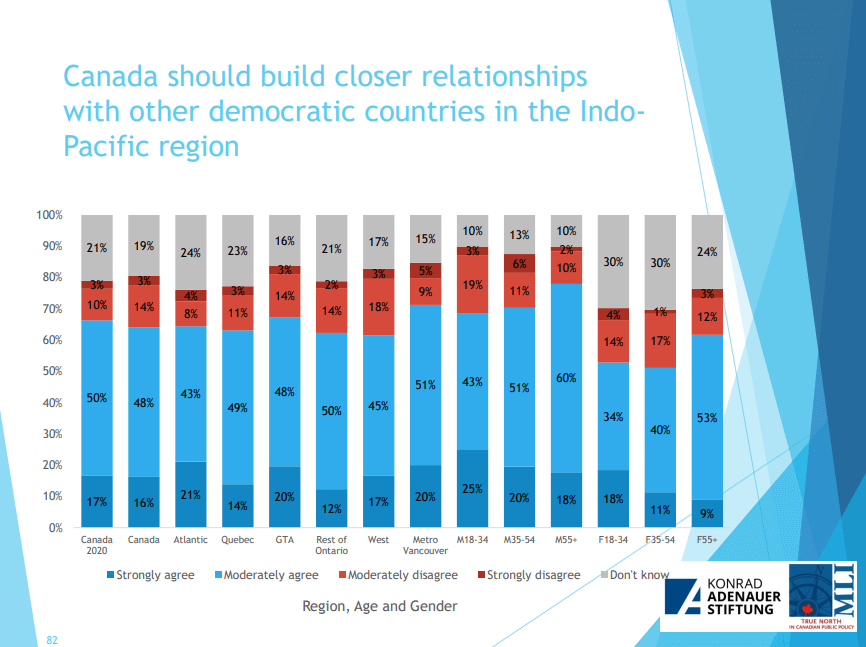

Additionally, with the government supposedly set to imminently release its Indo-Pacific strategy, 64 percent of Canadians believe we should build closer relationships with other democracies in the region. While this is relatively unchanged since last year, there is a growing negative opinion on this subject, which has shifted from 13 percent to 17 percent.

Additionally, with the government supposedly set to imminently release its Indo-Pacific strategy, 64 percent of Canadians believe we should build closer relationships with other democracies in the region. While this is relatively unchanged since last year, there is a growing negative opinion on this subject, which has shifted from 13 percent to 17 percent.

“Canada is an Indo-Pacific country, and finding our place in this region is crucial for Canada to succeed in the coming decade and beyond,” argues Miller. “Canada’s role in the Pacific and Indian Ocean Rim region must shift from one of a fair-weather trading partner to a regional power engaged on a number of fronts, from economic and trade to security and defence.”

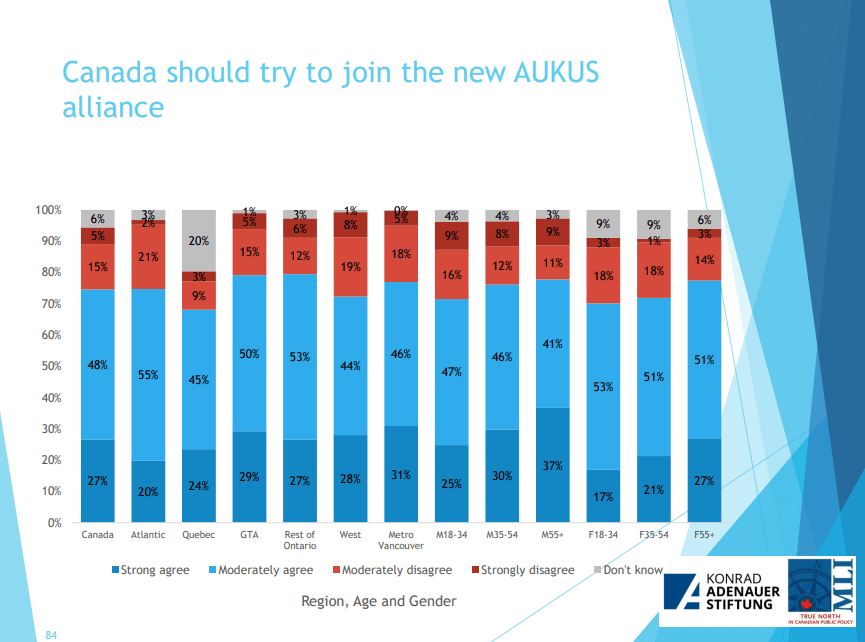

Speaking of the Indo-Pacific, Canadians overwhelmingly believe that Canada ought to try to join the new AUKUS alliance (75 percent). Canadians are close to four-times as likely to believe Canada ought to join AUKUS as they are to disagree, and Canadians are over five-times more likely to be strongly in favour as they are to be strongly opposed.

Speaking of the Indo-Pacific, Canadians overwhelmingly believe that Canada ought to try to join the new AUKUS alliance (75 percent). Canadians are close to four-times as likely to believe Canada ought to join AUKUS as they are to disagree, and Canadians are over five-times more likely to be strongly in favour as they are to be strongly opposed.

Taken together, Canadians are clearly of the view that our country should seek to bolster its involvement in multilateral and minilateral organizations that are oriented around fellow democracies. The data suggest a principled approach to foreign policy that neither shuns international organizations nor acquiesces to them when doing so is against our interests would be broadly supported by Canadians.

NATO and Defence Policy

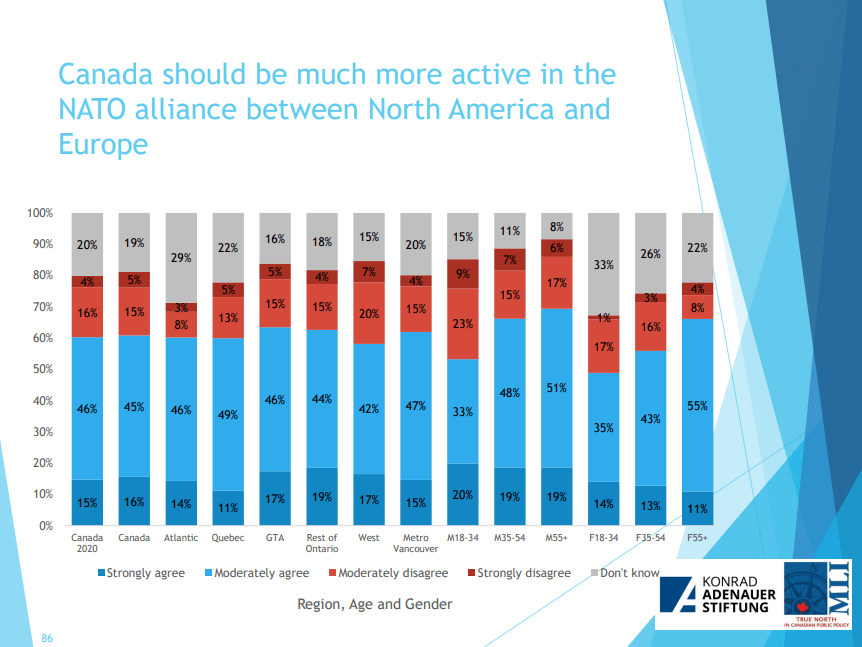

Canadian views on whether we ought to be more active in NATO remain virtually unchanged, with 61 percent agreeing at least moderately that Canada ought to be much more active in NATO. As IKS increases, so too does the conviction that Canada should be more active in the Alliance

Canadian views on whether we ought to be more active in NATO remain virtually unchanged, with 61 percent agreeing at least moderately that Canada ought to be much more active in NATO. As IKS increases, so too does the conviction that Canada should be more active in the Alliance

Though perceptions of NATO itself remain relatively unchanged, there has been a significant increase in Canadians (30 percent) who think Canada should withdraw from NATO to focus on other parts of the world. This is over double the number of Canadians who held that position (12 percent) in 2020. Even still, Canadians remain more significantly likely to disagree with the statement (49 percent).

Those with positive views of Russia and China, as well as young men, are most likely to hold this view. People with negative views of NATO are understandably more likely to believe that Canada should be less active in the Alliance or ought to withdraw from it. Differences in opinion do not track strongly with IKS score.

Yet over half (58 percent) of those who want Canada to leave NATO and focus elsewhere have a positive view of the Alliance, suggesting it is not a dislike of NATO per say, but rather a desire to look beyond the transatlantic community that is chiefly responsible for these opinions.

The growth of this view is perhaps more understandable when considering how Canadians view China as the biggest threat to Canada, and support greater engagement in emerging alliances like AUKUS. Further analysis of Canadians changing perspectives on NATO are needed to draw firm conclusions.

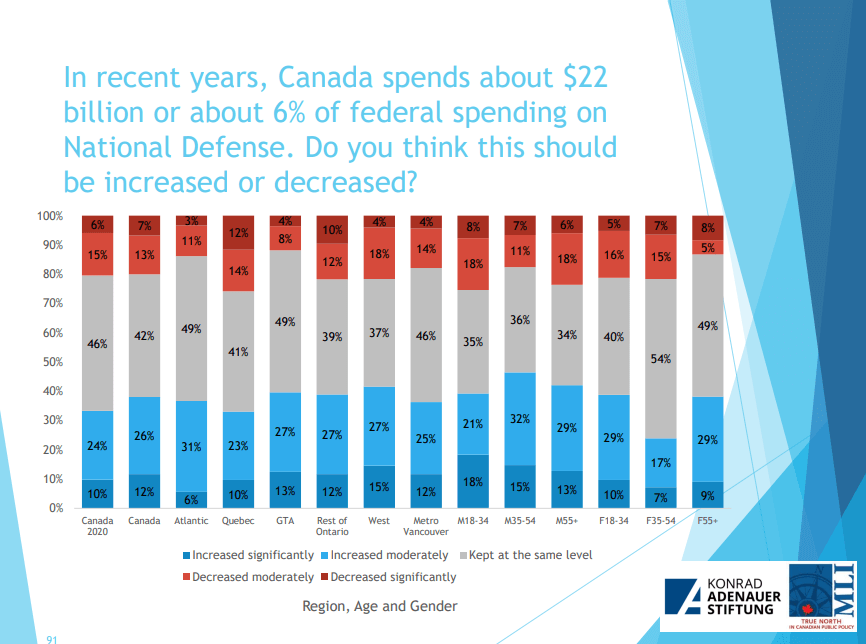

When presented with Canada’s defence budget and how much federal spending it represents, Canadians are more likely to support increasing national defence spending: 38 percent of Canadians want to see an increase in defence spending, a 4-point increase from 2020. Canadians are almost twice as likely to support increasing defence spending as they are to oppose it (20 percent). Even still, the largest cohort (42 percent) believe that defence spending ought to remain at the same level.

When presented with Canada’s defence budget and how much federal spending it represents, Canadians are more likely to support increasing national defence spending: 38 percent of Canadians want to see an increase in defence spending, a 4-point increase from 2020. Canadians are almost twice as likely to support increasing defence spending as they are to oppose it (20 percent). Even still, the largest cohort (42 percent) believe that defence spending ought to remain at the same level.

Canadians for whom foreign policy is important for their vote were the most likely group to believe that defence spending ought to be increased (57 percent). Predictably, those for whom foreign policy was not at all important were least likely to agree with increasing the defence budget (26 percent) and were in fact somewhat more likely to believe that it ought to be reduced (29 percent).

Foreign policy priorities

In 2020, we asked Canadians what they thought of some of Canada’s stated foreign policy priorities. For this round of polling, we asked them what they thought of some alternative foreign policy priorities, ones that reflect a more assertive and Canada-centric vision of foreign policy.

Though the questions asked this year have changed, what remains the same is this: Canadians tend to have a wide range of different and important foreign policy priorities. Of all the priorities listed, the perception of their importance rises as IKS increases, suggesting that the more informed Canadians are, the more likely they are to perceive issues of foreign policy as pressing priorities.

Eighty-seven percent of Canadians believe that defending Canadian values on the world stage, such as human rights and democracy, is important. A similar number (85 percent) believe that pursuing jobs and economic growth in international markets is important. When it comes to working with our allies to stand up to authoritarian regimes like China, 85 percent of Canadians find this important. And 88 percent agree that defending the interests of Canadian people and organizations abroad is important. Modestly fewer Canadians (82 percent) feel that defending our interests and sovereignty in the Arctic is important.

Of these priorities, Canadians are most likely to say that defending Canadian values on the world stage, such as human rights and democracy, is very important (50 percent). “Working with our allies to stand up against authoritarian regimes like China” comes second in the “very important” category (46 percent).

For Devlen, taken together this means that “a more assertive approach to foreign policy would be well-received by Canadians, particularly one that is centered around our shared values.

“Canadians, particularly well-informed Canadians, appear to be strongly in favour of foreign policy priorities that leverage our status on the global stage and align our values and interests in pursuit of our national interest.”

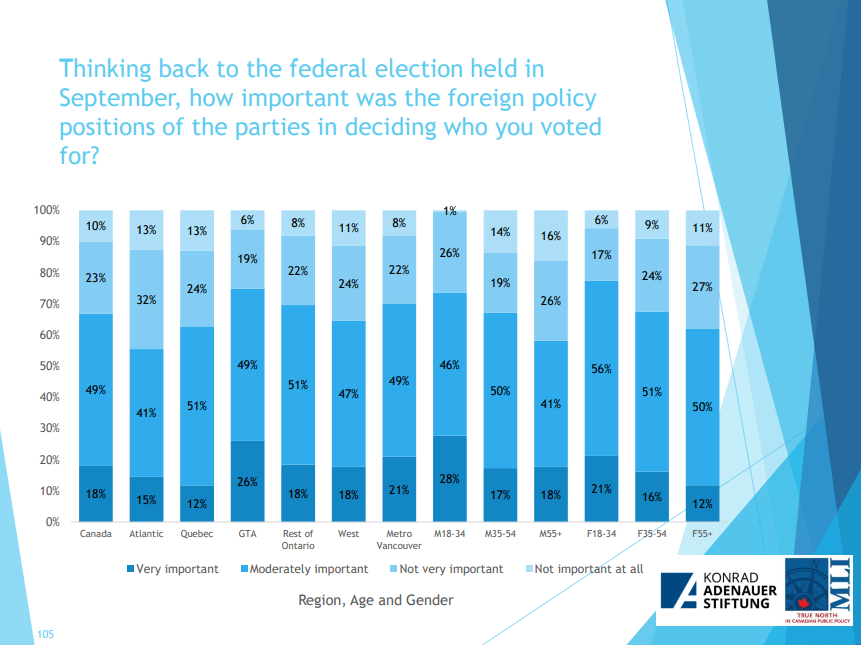

Foreign Policy and Voting

Though the proportion of Canadians who believe that foreign policy is at least somewhat important to their vote remains unchanged from 2020 (67 percent), Canadians are somewhat more likely to strongly believe that foreign policy is important. We can say that these “foreign policy voters” grew from 14 percent in 2020 to 18 percent in 2021.

Though the proportion of Canadians who believe that foreign policy is at least somewhat important to their vote remains unchanged from 2020 (67 percent), Canadians are somewhat more likely to strongly believe that foreign policy is important. We can say that these “foreign policy voters” grew from 14 percent in 2020 to 18 percent in 2021.

Foreign policy voters are more likely to be: in the GTA (26 percent), young men (28 percent), living in households earning over $150,000 (28 percent), immigrants to Canada (35 percent), and have medium or high IKS (33 percent). Conservatives and Liberal voters were equally likely to be foreign policy voters, but NDP voters were significantly less likely to fall into this category.

“Foreign policy voters remain a modest segment of the population, but make up an important constituency which political parties should be aware of,” says Majumdar. “While perhaps not the most important issue to most voters, it should be noted that 83 percent of immigrants to Canada report that foreign policy was either very or moderately important in terms of informing their vote in 2021.

“If political parties can set the agenda on these issues and articulate clear policies that resonate with voters, it stands to reason that there is plenty of potential for accessing and attracting new voters.”

2021 saw an increase in concern surrounding foreign disinformation, interference, and influence. As MLI’s DisinfoWatch project has found, foreign state media and actors have targeted Canadian issues and interests with information operations, and there are concerning signs that foreign interference did sway some voters.

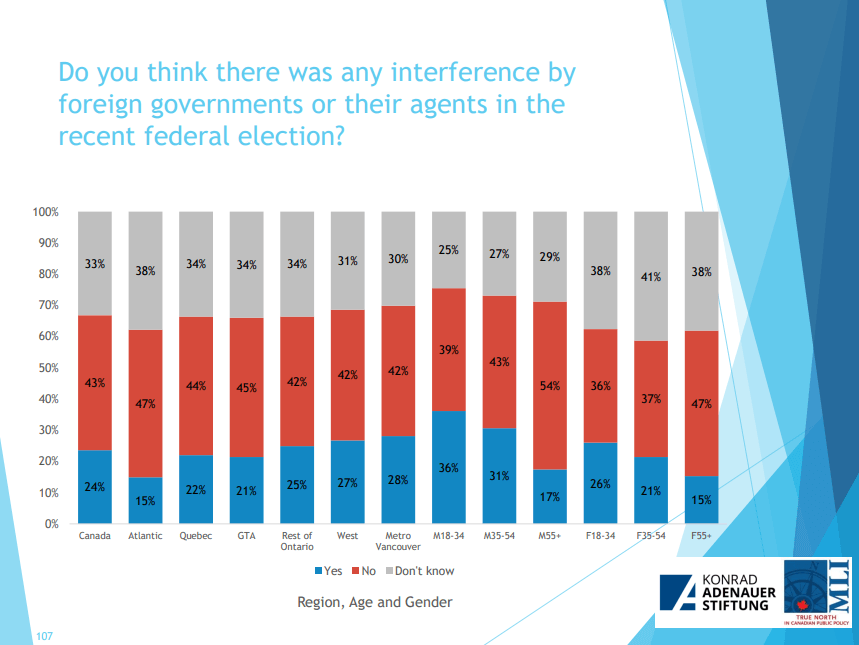

In general though, Canadians are more likely to believe that foreign election interference did not take place in 2021 than they are to believe that it did take place (43 percent to 24 percent, respectively). People in Metro Vancouver, men under 55, the well off, the well-educated, Conservatives, people with medium IKS and foreign policy voters are all more likely to believe this occurred. Foreign policy voters were the most likely group to believe that interference occurred at 45 percent, against 35 percent of these voters who do not believe that interference occurred.

It is important to note the marginal difference between Conservative and Liberal voters on this subject. Twenty-nine percent of Conservatives believed that foreign interference took place in the election, as did 24 percent of Liberal voters. This suggests that, unlike highly polarized discussions of interference in the United States, Canadians are like-minded on the likelihood that interference occurred. In other words, as of December 2021, the issue of foreign interference in elections is not a partisan issue in Canada and thus it is important to keep it as such and not turn into a political wedge to effectively address this threat to Canadian democracy.

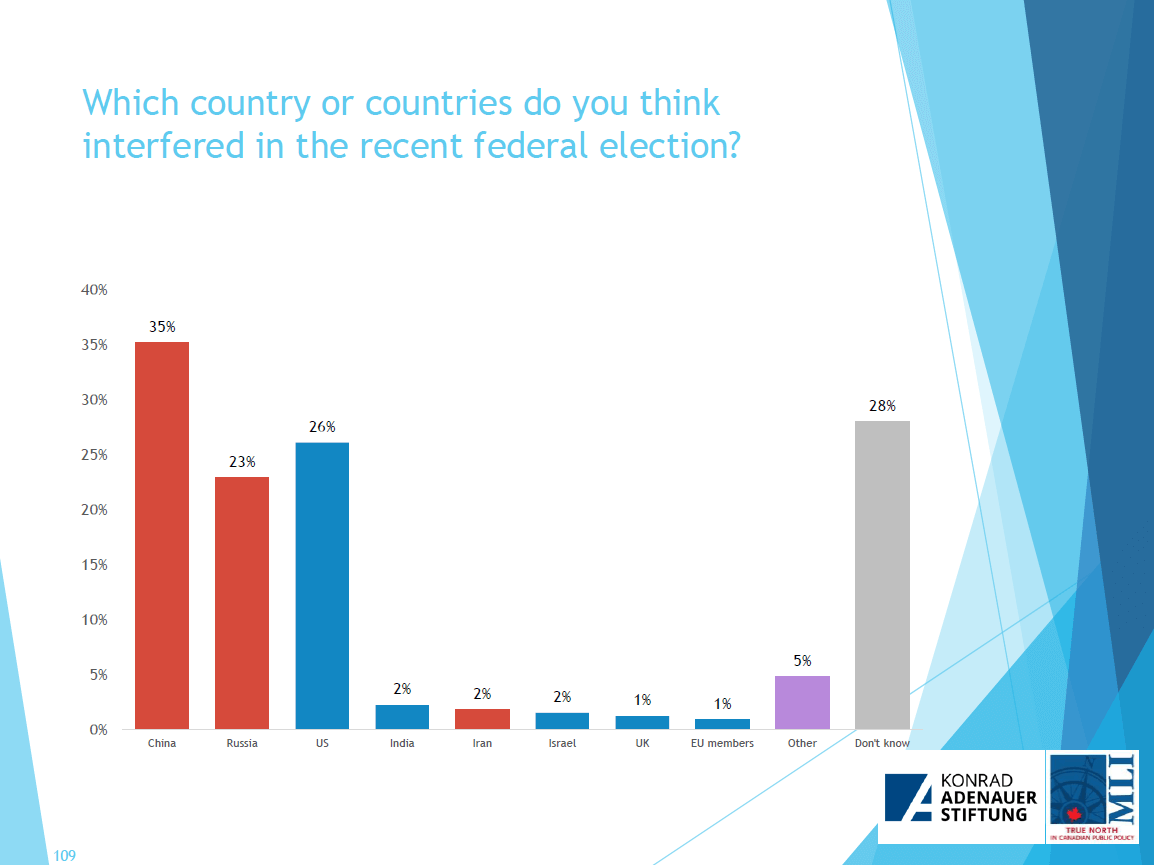

Of those who believe electoral interference took place, the most common suspects were China (35 percent), the US (26 percent) and Russia (23 percent). Twenty-eight percent did not know which countries were most likely to have interfered in the federal election.

Of those who believe electoral interference took place, the most common suspects were China (35 percent), the US (26 percent) and Russia (23 percent). Twenty-eight percent did not know which countries were most likely to have interfered in the federal election.

“Canada’s intelligence agencies and the available information is clear: there were attempts made by foreign governments and their agents in Canada toward interfering with Canada’s election,” argues Kolga. Interference does not have to be overt vote rigging or an election “steal” as some fear. Often it is more subtle, targeted, and “just under the radar enough that it does not arouse suspicion.”

As Kolga concludes, “It is therefore no surprise that most Canadians, particularly those with lower information and interest in foreign policy generally, do not believe that this kind of interference has occurred.”

Conclusion

The past year saw Canada turn somewhat more inward in terms of how it viewed the world and the issues in it. Canadians had somewhat lower information in 2021 than in 2020, with lower levels of engagement, less intense views of other countries, and some increasing credulity about the nature of hostile foreign regimes. With vaccines and lockdowns, elections, inflation, residential school revelations, and all manner of other concerns on the domestic front, it is perhaps not surprising that Canadians’ attention has shifted from the global stage.

Even still, Canadians remain largely clear-minded in identifying our allies and adversaries. Though opinions have softened, Canadians generally understand which countries can help advance our interests, and which countries seek to undermine them.

We are reminded that Canadians are saturated with American news. The defeat of President Trump has led to a complete reversal of Canadian public opinion toward the United States. The deep connection between what Canadians think of a country’s political leaders and what Canadians think of the country more generally presents challenges for policy-makers whose relationships with important allies must be more resilient than the political winds of the day. Canada needs to have a pragmatic and party-agnostic policy towards the US, an issue that American political leaders would be well advised to learn. The Canada-US relationship, after all, is our country’s most important economic, foreign, and security relationship.

Canadians remain supportive of the international system and the organizations in which Canada is a member. While support for NATO has dropped, this drop can perhaps be explained by a push to look toward other regions and alliances, such as those in the Indo-Pacific. Support for AUKUS is particularly strong and notable, particularly given how little it has been debated publicly. The Anglosphere also continues to play an important role in the worldview of Canadians when it comes to international affairs, this being evident in views towards the UK, Australia as well as Five Eyes.

Clear cohorts of foreign policy voters have emerged; building off 2020’s trends, we have seen that new Canadians are often more likely to be aware of the threats to Canada, support involvement in international alliances and want our country to stand up for democratic values around the world. Those with the strongest opinions on foreign policy tend to be older, richer, better educated, and better travelled than other Canadians. They also include immigrants and newcomers to Canadian democratic life.

We also see an intensification of this bifurcation. In other words, those foreign policy voters are even more intense in their views while those who do not see foreign policy as important are even more disinterested. A healthy democracy needs an informed and engaged citizenry, not only on domestic issues but also on their foreign implications. Thus, addressing this information and interest gap remains an important task.

The conversation on foreign interference in Canada is nascent, despite warnings from experts and security agencies about the real and present danger posed by foreign actors. More work must be done to increase public knowledge on these issues in a fact-based, non-partisan fashion.

But most importantly, Canadians largely support a stronger, more principled foreign policy for Canada that asserts our interests, stands up for democracy, and works hand in hand with our allies and partners. Revealed through this polling is the fact that politicians and policy-makers have opportunities to seize on easy wins and should do so with urgency to ensure that Canada’s interests abroad are secured.