This article originally appeared in the National Review.

By Peter Menzies, August 9, 2023

Here’s a word of caution for policy-makers looking to help publishers retrieve some of their advertising revenue lost to web giants such as Google and Meta: Whatever you do, don’t look to Canada for inspiration.

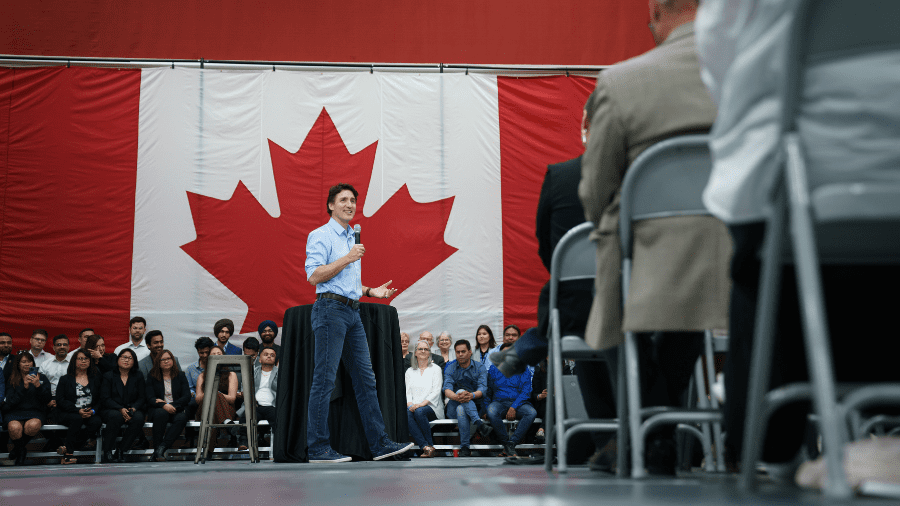

Canada’s efforts to “defend democracy,” as Prime Minister Justin Trudeau put it, have turned out to be a counterproductive fiasco. The government hoped the Online News Act would salvage a struggling legacy news industry and become a model to be copied globally. But it is the most spectacular legislative failure in Canada’s living political memory.

Inspired by an Australian publishers-collective that managed to squeeze deals reportedly amounting to as much as U.S. $150 million annually from Meta and Google, Canada’s Online News Act forces those same tech companies, provided they facilitate the sharing of links to access news stories, to pay for the privilege of doing so, even if the service is provided for free. As was the case in Australia, Canada’s legacy newspaper companies — the largest of which is owned by a New Jersey hedge fund — insist the American platforms have been “stealing” their content and profiting from it.

The tech companies say there is little commercial value in news. They’ve already been working to support journalism through different commercial and philanthropic arrangements and say that, between them, they provide just under $500 million CDN worth of access to people for free.

The Online News Act sides with the Big Tech–thievery version of events and compels the accused to strike deals with news organizations, using a baseball-style winner-take-all arbitration process to settle matters if needed. The government and its backers have argued steadfastly that in the end, a portion of Canada’s $12 billion CDN digital-advertising market (80 percent of which has been won by Meta and Google) will be returned to those from whom it has been “stolen.”

As a result, Meta has concluded its only option is to “comply” with the legislation by beginning to move out of the business of carrying news links on Facebook and Instagram; Meta says it will complete the process before the Act comes into force toward the end of the year. Google also announced it would no longer be including Canadian news organizations in online searches performed in Canada.

Panicked efforts by the government to see if some sort of accommodation can be introduced under the law have been rebuffed completely by Meta, which might retreat from the news-carrier business globally. Google is still speaking with the Canadian government, but the latter’s description of these conversations as “negotiations” is most likely an overstatement. Google’s decision last month to exclude Canada from its Bard AI chatbox launch indicates the mood isn’t great.

Unless Trudeau’s team can cap Google’s liability at an agreed-upon level and future-proof that cap — sources indicate an extra $100 million annually is Google’s firm offer — it appears Canada is on the verge of destroying far more journalism jobs than it ever could have hoped to save.

The loss of access to Meta’s Facebook and Instagram platforms would be, Canada’s already-struggling publishers said in Senate hearings, disastrous and amount to millions of dollars in losses. For emerging and innovative providers — 217 have launched in Canada since 2008 to offset the disappearance of an estimated 450 newspapers — the impact is considered even more devastating. Most (if not all) of them have built their business models on maximizing the value they receive through Google and, primarily, Facebook.

In addition to assuming the accuracy of the “theft” narrative, the drafters of this legislation were determined to position the Trudeau government internationally as a world leader in bringing Big Tech to heel. In doing so, they failed to listen to critics who pointed out that putting a price on links was a foolish way to go about it. And, while fueling wild expectations of a new and lucrative income stream for domestic news organizations, the drafters forgot (or chose to ignore) the reality that no executive in any industry would agree to a deal in which there was no cap on his or her company’s potential liability. Throw into the mix that whatever dollar figure was agreed to in Canada was going to be multiplied by at least 50 if the rest of the world replicated Trudeau’s legislation and, well, here we are.

Canada bet that Google and Meta were bluffing. What is clear is that there was no backup plan just in case they weren’t.

Peter Menzies is a Senior Fellow with the Ottawa-based Macdonald-Laurier Institute, former publisher of the Calgary Herald and a past vice-chair of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission.