By Jon Hartley, Filip Jolevski, Vitor Melo, and Brendan Moore

October 14

Canada risks falling dangerously behind in the global race to harness the productivity-enhancing power of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). Despite its world-class universities, highly educated population, and a history of AI research excellence (particularly emanating from the Greater Toronto Area), Canada’s workplace adoption of GenAI is currently less than half that of the United States.

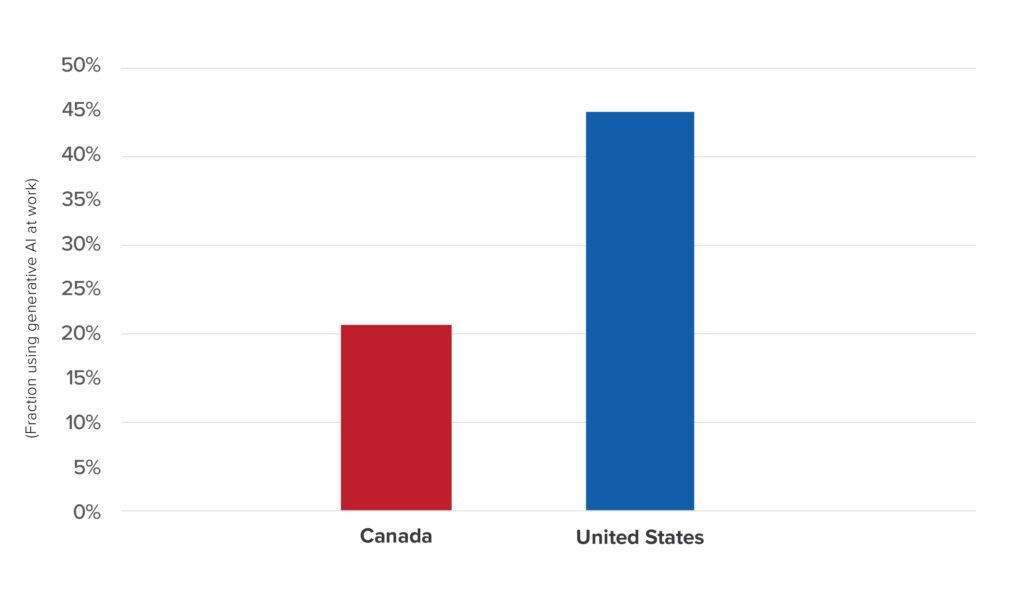

According to surveys we have been running, only 21.2 per cent of Canadian workers are using GenAI tools like ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini in their daily jobs – compared to 45.6 per cent in the United States as of mid-2025 (see Figure 1).

This stark contrast should be a wake-up call to Canadian policymakers, business leaders, and educators.

We think the widespread and effective use of Gen AI technologies will be one of the defining factors separating the prosperous economies of the 21st century from those mired in stagnation. For Canada – where GDP per capita has been largely flat for nearly 15 years – closing this GenAI gap is not just an economic opportunity, but an imperative.

Falling behind in a technological arms race

The global economy is entering what Jensen Huang, founder and CEO of Nvidia, aptly calls the “AI industrial revolution.” As he has recently warned, “You are not going to be replaced by AI, but you will be replaced by someone using AI.” This is not a threat, it’s a diagnosis. The point is simple but profound: individuals, firms, and countries that fail to learn how to leverage GenAI will fall behind those that do.

The data from our national Canadian survey confirms this. GenAI users in Canada report average time savings of 73.4 per cent on AI-enhanced tasks – transforming multi-hour writing or analysis assignments into activities completed in under an hour. These tools are not simply automating busywork – they are augmenting and accelerating critical thinking, problem solving, and creative output across a range of industries.

Yet in Canada, only about one in five workers are using these tools. The United States, in contrast, has already moved into a second wave of adoption, with nearly one in two professionals integrating GenAI into their workflows. This gap is not merely academic. It represents a widening productivity chasm that could compound over time, as American workers become vastly more efficient than their Canadian counterparts.

Perhaps, larger, richer firms in the US can more easily invest in Generative AI subscriptions than poorer and smaller Canadian firms. But this is no excuse not to invest in productivity-enhancing technology.

Stagnation and structural weakness

The timing of Canada’s lag in AI adoption could not be worse. Since the mid-2000s, Canadian GDP per capita has grown at a sluggish pace, underperforming not only the US but also many peer economies. Productivity growth – defined as output per hour worked – has been alarmingly weak, held back by underinvestment in both physical and human capital.

Rather than closing the productivity gap with the United States, Canada risks falling further behind. While the US is integrating GenAI into finance, health care, law, logistics, and public administration, Canadian organizations remain tentative. While American companies train entire divisions in prompt engineering, text generation, and AI-assisted coding, many Canadian firms have yet to issue their first internal AI policy.

There is an economic cost to inaction. Generative AI is not a future abstraction. It’s a general-purpose technology (GPT) potentially on par with the internet or electricity. The gains from early adoption are large and compound rapidly. As Canada hesitates, it may lock itself into a path of lower productivity, reduced competitiveness, and weaker income growth.

Why Canada is lagging – and why it can’t afford to

Our survey of 2,478 Canadian workers highlights several structural reasons for the country’s lower adoption of GenAI, which are worth paying attention to:

- Demographic inertia: The average GenAI user in Canada is 40.7 years old, while the average non-user is 51.2 years old. This 10.5-year age gap signals a digital divide where younger, more tech-savvy workers adopt AI while older cohorts lag.

- Educational divide: 57.5 percent of GenAI users hold a bachelor’s or graduate degree, compared to just 26.7 per cent among non-users. Workers without post-secondary education are being left behind in the AI transformation.

- Public sector resistance: Adoption rates in the private sector are 36.6 per cent, compared to just 26.9 per cent in government. Bureaucratic inertia, data security concerns, and rigid IT systems are slowing public sector integration of GenAI tools.

- Regional disparities: Adoption ranges from a high of 25 per cent in Ontario to just 13.3 per cent in Newfoundland and Labrador. Canada’s innovation economy is urban and uneven, leaving rural and smaller provinces behind.

These divides risk entrenching a new digital inequality in the Canadian workforce – by age, by education, by region, and by sector. If unaddressed, this may very well weaken national productivity and deepen labor market segmentation.

The case for workforce training and re-skilling

The answer to this lag is not top-down industrial policy or protectionism. It is investment in human capital – specifically, in digital literacy and GenAI competency across the workforce.

Canada must act urgently to train workers not merely to coexist with GenAI but to thrive alongside it. This means:

- Integrating GenAI training into public education, vocational programs, and university curricula. Prompt engineering, critical evaluation of AI outputs, and domain-specific use cases should be taught just like Excel or coding. The Canadian public post-secondary education system has the capability of doing this at scale.

- Offering employer incentives to fund GenAI workshops and internal learning programs, especially for small and medium enterprises that lack the scale of large corporations.

- Launching regional re-skilling initiatives in areas where GenAI adoption lags, particularly in poorer provinces and those with traditional manufacturing sectors.

- Equipping public servants with the tools and training to use GenAI to improve service delivery, policy research, and regulatory efficiency.

Canada’s current adoption gap reflects a lack of digital capacity, not capability. The productivity gains of GenAI are not limited to computer scientists or Silicon Valley engineers. In our survey, GenAI delivered similar time savings across all income levels – from factory-floor workers to white-collar professionals. This technology has the potential to democratize productivity – but only if Canadians are trained to use it.

GenAI Is an equalizer – if we let it be

Contrary to fears that GenAI will widen poverty, our findings suggest it could do the opposite and be a leveler between skilled and unskilled workers. Anyone who didn’t know how to code before now has the means of doing so through an LLM (large language model ) prompt.

Workers earning between $35,000 and $74,999 saw efficiency gains on par with high-income earners in our survey. In fact, lower-income workers were slightly more likely to report extreme time savings (90 per cent+), suggesting that when given the right tools and training, GenAI can level the playing field.

But access to those tools and skills is not automatic. Without targeted efforts to expand adoption, existing educational and regional divides may worsen and GenAI could remain highly concentrated amongst high-skilled service workers in the wealthiest metros of Toronto, Ottawa, and Vancouver.

That is not a recipe for broad-based economic growth. If Canada wants GenAI to boost national productivity – not just raise the wages of software engineers – it must pursue inclusive diffusion. That means building infrastructure and training pathways so that a tradesperson in Winnipeg or a small business owner in Moncton has the same GenAI fluency as a McKinsey consultant in downtown Toronto.

Embracing a culture of AI-driven innovation

Canada’s approach to GenAI adoption must also be cultural. While the US tech ecosystem embraces experimentation and iteration, Canadian firms often exhibit risk aversion. Government regulations and institutional inertia – especially in the public sector and regulated industries – are compounding the problem.

This is not a call for reckless deregulation. But Canada must adopt a pro-innovation regulatory posture that allows for controlled experimentation with GenAI in health care, education, and public services. Regulatory sandboxes, outcome-based oversight, and clear guidelines on responsible use can unlock innovation while protecting citizens.

Equally important is executive leadership. GenAI adoption is often top-down – when CEOs use these tools themselves, their organizations follow. Canada needs more business leaders to model AI fluency and evangelize its benefits. In our data, the highest GenAI adoption rates are found in management occupations (52.9 per cent) – proof that when leaders lead by example, adoption follows.

Time for Canada to catch-up

The global GenAI race is already underway, and Canada is starting from behind. At 21.2 per cent workplace adoption, Canada is not just behind the US (45.6 per cent) – it is behind its own potential. With weak productivity growth, stagnant GDP per capita, and rising global competition, Canada cannot afford to sit out the next technological revolution.

Generative AI will not replace Canadian workers. But as Jensen Huang said, workers using GenAI will replace those who don’t learn how to use it. The same could be true across countries. Nations that invest in AI fluency – through training, education, cultural acceptance, and regulatory flexibility – have an opportunity surge ahead. Those that do not may very well stagnate.

Generative AI will not be without ethical challenges. Policymakers, business leaders, and educators will need to grapple with concerns around bias, transparency, and accountability. Large language models can inherit, and even amplify, biases embedded in their training data, leading to outputs that may be discriminatory or misleading. Without ongoing monitoring and clear disclosure standards, GenAI risks eroding trust among both users and the public. Equally important is ensuring transparency in AI decision-making processes. If GenAI tools are used to influence hiring, lending, or public policy in any way, stakeholders must be able to understand how outputs were generated, on what data they were based, and where potential errors could arise. The last thing we want are “hallucinations” (false information created by GenAI tools) propagating in society. Lawyers and legal scholars around the world have accidentally cited fake cases by using Generative AI tools to write legal memos and opinions. Such behavior deserves to be scolded and reprimanded.

Privacy and data governance present another significant ethical frontier. Many GenAI systems rely on sensitive or proprietary information to produce high-quality results. Without strong safeguards, there is a risk of unauthorized data exposure or misuse, particularly in sectors like health care, finance, and government. These challenges demand not only robust technical solutions – such as encryption, anonymization, and secure APIs –but also clear legal and ethical frameworks to guide implementation. Responsible adoption means building systems that protect individual rights, respect intellectual property, and maintain public confidence, while still enabling innovation.

Canada has the talent, the institutions, and the infrastructure to lead in GenAI. But it must overcome its hesitation. It must build a culture of AI-driven innovation that includes every worker, every industry, and every region. The alternative is clear: an economy increasingly defined by slow growth, underutilized talent, and missed opportunities.

The path forward is not complicated. It starts with national ambition – and ends with widespread AI literacy. Now is the time to act.

About the authors

Jonathan S. Hartley is a Hoover policy fellow at the Hoover Institution, a research fellow at the University of Texas at Austin Civitas Institute, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and an affiliated scholar at the Mercatus Center. Hartley is also the host of the Hoover Institution podcast Capitalism and Freedom in the Twenty-First Century, a member of the Canadian Group of Economists, and the founding chair of the Economic Club of Miami. He is also an economics PhD candidate at Stanford University.

Filip Jolevski is an economist with his research focused on industrial organization and technology adoption. He is a Senior Affiliated Scholar at the Mercatus and holds a PhD in Economics from George Mason University.

Vitor Melo is an associate economist at Rand Corporation and a former lecturer in the Wilbur O. and Ann Powers College of Business at Clemson University.

Brendan Moore is a labor economist and economics PhD student at Stanford University. He specializes in the causes and consequences of job loss, and much of his recent research studies unemployment insurance policies.