This article originally appeared in the Washington Times.

By Brian Lee Crowley, August 8, 2023

Last week, in a hearing to confirm NORAD’s next commander, Sen. Dan Sullivan, Alaska Republican, caused a stir when he called Canada a persistent defense free-rider. He added that “Americans get frustrated when our allies don’t pull their weight.” The U.S. ambassador to Canada, David Cohen, immediately rose to Canada‘s defense.

Who’s right? Certainly not Mr. Cohen.

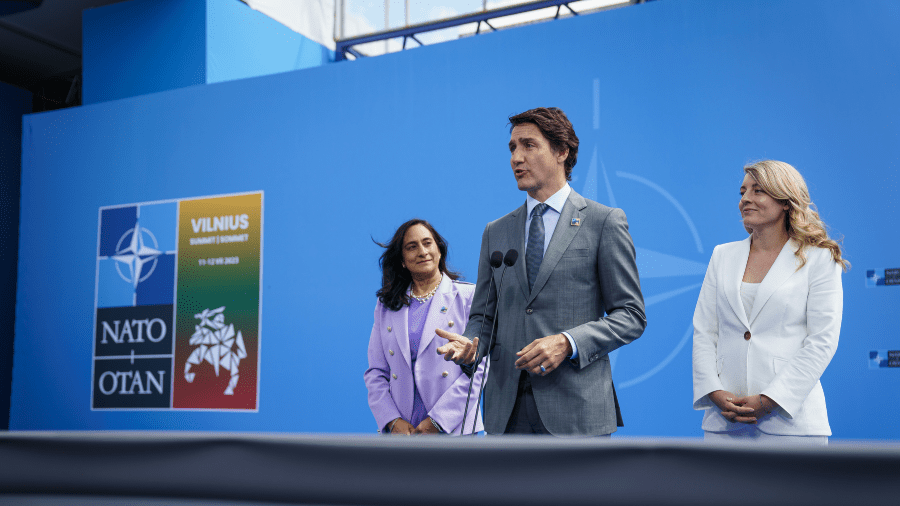

At the NATO summit last month in Vilnius, Lithuania, President Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, said: “Spending two percent of [gross domestic product] or more is necessary to ensure the security of the Alliance. It is the minimum necessary now. We will not stop putting pressure on countries that do not meet this requirement.”

When then-President Barack Obama addressed Canada’s parliament in 2016, he argued, “We’ll be more secure when every NATO member, including Canada, contributes its full share to our common security.”

Mr. Cohen knows this. Yet in the face of Sen. Sullivan’s comments, Mr. Cohen unhelpfully repeated the talking points of Canada’s Liberal Party prime minister, Justin Trudeau: “I think it would be a bad mistake — and I frankly think that too many people are making this mistake — that somehow we need to assess Canada‘s commitment to defense by one metric. I don’t think that’s right.”

The principle of burden-sharing is central to NATO, and Canada‘s defense spending falls short of its allies’ expectations and its own promises, leaving a disproportionate burden on other member states. Washington, as Ottawa’s primary security guarantor, carries the largest burden.

The United States, Canada and our allies are faced with profound geostrategic challenges — primarily from Russia and China. Yet Ottawa has consistently ducked out on paying its share of the bill, with defense spending stuck at approximately 1.3% of GDP.

Making matters worse, Mr. Trudeau has indicated that Canada not only will not honor a 2% spending target now, but told his allies privately that Canada has no plans to ever achieve it.

He cannot plead poverty: His own government has increased its spending by $151 billion in seven years, with the federal public sector ballooning by 31%, or 80,000 employees. It recently promised as much as $30 billion in new subsidies — equal to Canada’s entire defense budget — for electric vehicle battery plants. Yet it cannot seem to find the $15 billion needed to get to the 2% target.

Messrs. Trudeau and Cohen say that the 2% goal doesn’t tell the whole story. They rightly point to important roles Canada has taken on for the alliance.

Fair enough. Canada, for example, is leading the NATO tripwire mission in Latvia. Yet here, too, Canada’s miserliness on defense is a problem.

Ottawa is struggling to find the resources to get its NATO mission in Latvia to brigade strength. Its proud peacekeeping tradition is in tatters for want of soldiers and materiel. In any event, these missions are a red herring in the context of the minimum spending NATO’s own members have agreed is necessary to sustain the alliance.

Moreover, Ottawa is not just lagging on spending, but also in terms of the unique capabilities America and the rest of the alliance can and should look to Canada to supply. According to recent reports, for example, Canada has a paltry 300 military personnel stationed in its vast Arctic at a time when not only Russia but even China, which doesn’t have an Arctic coast, are building major Arctic military and economic capacity.

Similarly, Canada has been foot-dragging for years on the money needed to modernize NORAD, on which both Canada and the U.S. depend for their air and maritime security. Mr. Trudeau vaunts his plans to increase spending in some of these areas but neglects to say that his much-ballyhooed spending announcements are often quietly shelved, unmet, at the end of the year.

Finally, Mr. Trudeau recently dismissed urgent calls from Canadian defense experts for more spending, suggesting that such spending is a low priority. Yet a recent poll from Nanos, one of Canada’s top pollsters, shows that approximately two-thirds of Canadians agree that Canada needs to honor its promises on defense.

Next year, NATO will mark its 75th anniversary with a summit in Washington at a time of heightened tension with both China and Russia. That should be an occasion for Canada’s friends and allies to speak frankly to Canada about its misguided and damaging tight-fistedness on defense.

In the meantime, word should reach Mr. Cohen from Washington that his job is not to have Mr. Trudeau’s back in the face of his critics, but to represent America’s interests, even if that means tough talk to his hosts. He certainly shouldn’t be making harder the job of those Canadians pressing the case for a more honest, honorable and muscular defense commitment from their politicians.

Brian Lee Crowley is managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, an independent public policy think tank in Ottawa.