Writing in the National Post, author John Pepall writes that those who constantly fret over the state of Canadian democracy are distracting from the important debates that we should be having over public policy issues.

Writing in the National Post, author John Pepall writes that those who constantly fret over the state of Canadian democracy are distracting from the important debates that we should be having over public policy issues.

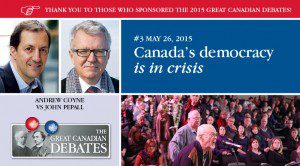

Pepall argued against the resolution “Canada’s democracy is in crisis” for the third Great Canadian Debate of 2015, held on May 26, 2015 at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

Andrew Coyne, who argued in favour of the resolution, also authored an op-ed for the Post.

By John Pepall, May 27, 2015

Crisis? What crisis? Our democracy is working fine and not at risk.

I am not happy with our politics. Governments at all levels are doing stupid things, bad things. And much that they should be doing, they are not doing. Our politicians are, many of them, a sorry lot, even some I have voted for.

Most people would agree with me that this is so, though not on the specifics: what governments have got wrong; what they should be doing; who are the political duds and which politicians deserve some respect. That’s what we should be talking about. Not some imagined crisis of democracy or, to put it less dramatically, democratic deficit.

There is no democracy out there, somehow occluded, that would bring us what would generally be rated excellent government and superb politicians. Nor is the problem democracy itself. Meritocracy, aristocracy, bureaucracy, theocracy won’t bring us happiness.

The point of democracy is not that the people know best, and with it working well, all will be happy. The point is that government is the people’s business. We all have to obey laws and pay taxes and need services governments provide and we should have our say on what they are.

“To govern is to decide,” the old saying goes and at any given time many of us, even most of us, will not like much of what governments decide, or what elections decide. Even governments checked and balanced into inertia would be deciding to do nothing when most people would want them to do something rather than nothing.

Too often when our governments decide on things people don’t like, people complain that the decisions are undemocratic, when they should be making the case that they are wrong.

People generally know people who share their thinking on politics. They follow media that reflect their thinking. They come to think that what they think most people think and that if that doesn’t prevail in politics, the people’s will, that is, the will of the people they know, has been frustrated by some democratic deficit.

The truth is that they are not winning the arguments. Perhaps because they are not arguing, not addressing the arguments of those who like what they don’t like, not considering that they may have a point, but assuming that what seems right to them must seem right to everyone.

This leads to a kind of self-righteousness in our politics — the notion that politicians doing what you don’t like are bad people acting dictatorially against what seems obviously the people’s will, because it is what all the people you know want.

At the same time it is obvious, and often remarked, that most politicians, most of the time, are trying to appeal to voters, their base, swing voters, the centre. Isn’t that democracy at work?

Many of the things those who fret about the state of democracy complain about can be explained by the attempt to appeal to voters: party discipline, lengthy leadership races, shambolic nomination contests, sound bites and even broken promises. But what are these “promises” that politicians break. They are offers to the voters of things they can’t have, something the politicians and the voters could know, but wouldn’t like to hear.

Indeed, the politicians who are most in favour are those who say that they just want to do what the people want, that they are sounding out their constituents and presenting their wishes, not just whatever they, the politicians, think, supposing they do think.

What these politicians find their constituents want has an odd way of coinciding with what the politicians have offered as their principles and their parties’ general positions. But the implication is that a politician who thinks X (I want to keep any specific policies out of this) would be a good thing, but finds the constituents are dead set against X, will denounce X vehemently. Is this honest? It is supposed to be very democratic.

All kinds of remedies have been proposed for our supposed democratic deficit. I wrote a small book explaining how they are all misconceived and likely to damage democracy.

These bad ideas are not just an accidental series of mistakes. They arise from the fundamental mistake of thinking that there is some institutional change that will assure that despite our different ideas and our conflicting interests, we can all be happy with our governments. There isn’t.

What we can and should be doing is arguing about the ideas and trying to find the commonweal above our particular interests. And then, come the elections, we can decide — something the voters of Alberta did earlier this month and we shall all do in October. Whatever the result, and whatever we may think of it, that is democracy. Those who fret about the state of democracy in Canada distract us from the real debates and risk denying us the ability to decide. They would put our democracy at risk.

John Pepall is the author of Against Reform (University of Toronto Press).