Writing in the National Post, columnist Andrew Coyne argues that Canadians have the form but not the substance of Parliamentary democracy.

Writing in the National Post, columnist Andrew Coyne argues that Canadians have the form but not the substance of Parliamentary democracy.

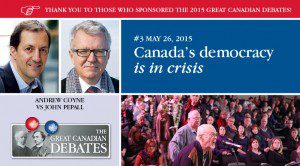

Coyne argued in favour of the resolution “Canada’s democracy is in crisis” for the third Great Canadian Debate of 2015, held on May 26, 2015 at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

John Pepall, who argued against the resolution, also authored an op-ed for the Post.

By Andrew Coyne, May 27, 2015

I suppose the best way to answer the question — is Canada’s democracy in crisis? — is to ask: what would a democracy that was not in crisis look like?

You could probably get some consensus for the following: everyone gets a vote and every vote counts equally. Candidates, nominated by local party members, stand for election on a pledge to enact certain policies if elected. Members of Parliament, once elected, propose, debate, scrutinize and vote on laws, mind the public’s money and generally hold government to account. The government, for its part, must hold the confidence of the legislature at all times, or else it falls.

Well, no, that’s too high a bar, isn’t it? What I’ve described is a democracy that works as it’s supposed to. If our democracy were only deficient in one or another item on that list — fair votes, meaningful elections, accountability to Parliament and so on — you might say it was unsatisfactory, but not “in crisis.” What makes the situation critical is that none of them apply.

Put simply, we no longer live under the system we think we do. We have the form of a parliamentary democracy, but not the substance; the rituals, but not the reality. It has declined to such a point that it has become, or is about to become, or threatens to become, something else.

Let’s follow the process from start to finish. Candidates are commonly not nominated by a vote of the existing party members in a given riding, but rather stage what are in effect putsches, stacking meetings with busloads of new recruits whose memberships as often as not have been purchased for them. That’s when they are not simply appointed, de facto or de jure, by the party leader. The leader will typically have been elected by the same process of mass membership sales or purchases — an electoral college that, uniquely in the democracies, vanishes the second it has done its work, leaving the leader accountable to no one.

The candidates may have thoughts on the issues, but it doesn’t really matter what they think, because all policy is set by the parties, which is to say by the leaders. And it doesn’t matter where the parties or the leaders stand, because at any given time they usually stand for the same thing, and because whatever they stand for today they will stand for the reverse tomorrow. Recent Canadian elections have set new standards for dishonesty: not just the usual calculated ambiguity, but flat-out lies, and not on minor platform details but often the central issue of a campaign.

The campaigns themselves are barely worth discussing: a blur of attack ads, photo ops, attack ads and news coverage heavily focused on polls, gaffes and inside-baseball discussions of strategy, mostly about attack ads. After which the votes are counted and we find we have elected a Parliament that looks nothing like what the voters cast their ballots for, with a distribution of seats, thanks to our wildly distorted system of representation, that bears no resemblance to the division of opinion in the country. Parties that concentrate their support regionally are massively favoured, electing many more members with many fewer votes than another party. In effect, this means each of their supporters has many times the votes of the other party’s. So much for one person, one vote.

Members of Parliament, it is by now well established, have no real role or responsibility but to stand up and sit down when told. They can’t vote except as the whips instruct, can’t speak or ask questions except as the whips permit. Perhaps one or another MP will be of a mind to rebel. Very well — good luck getting those nomination papers signed: by law, that’s the leader’s exclusive privilege.

Collectively, members of Parliament have very little ability to hold governments to account. They can’t get their questions answered, can’t get the documents they demand, can’t trust the figures in them when they do. Debates are now routinely cut off by a vote of “time allocation.” Committees increasingly meet behind closed doors, which is perhaps just as well, since their public hearings have become open farces.

The budget process has more or less completely broken down, the estimates released before the budget they are supposed to explain, each document expressed on a different system of accounts. Budget bills, meanwhile, have become the vehicle for passing the government’s entire spring or fall agenda — dozens of bills, of widely varying purpose — at one go. So even if debates or committee scrutiny still meant anything, they are now impossible, in the same way that it is now impossible to know what MPs meant by their votes on such disparate matters.

And on those rare occasions when a government is finally being held to account, when it is really feeling the heat — it prorogues. For months at a time. In some provinces of late, the legislature has taken to sitting for less than two months of the year. Even the confidence convention — the bedrock requirement that a government must command the confidence of the House — is under assault. Heading for certain defeat in a confidence vote in 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper simply prorogued. Having losta confidence vote in 2005, former Prime Minister Paul Martin spent the next nine days trawling the opposition benches, offering jobs and other inducements that were not constitutionally in his power to bestow, until with the help of a timely floor-crosser he was able to win a do-over.

Is it any wonder, surveying this wreckage, that so many voters have tuned out completely? At the federal level, turnout has fallen from an average of roughly 75 per cent in the postwar decades to a little more than 60 per cent. Turnout in provincial elections is even worse; municipal turnouts, lower still. Recent federal byelections have seen turnouts of less than 20 per cent. “Majority” governments are now formed in this country with the support of barely one in five adult citizens — about the same as a century ago, before women were allowed to vote.

Bogus nominations, skewed elections, powerless parliaments, disappearing voters. Let me invert my opening question. If that is not a system in crisis, what is?