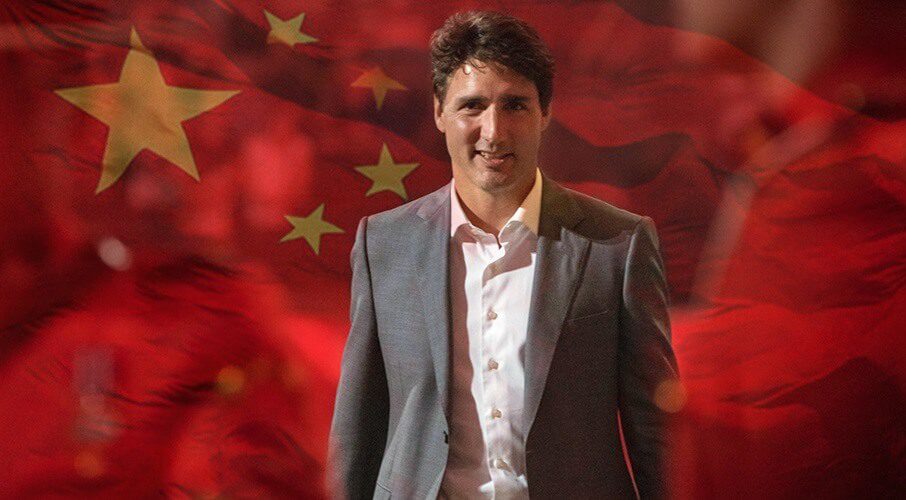

The Meng Wanzhou affair is a wake-up call: Canada needs to get serious about the China challenge, writes Richard Shimooka.

The Meng Wanzhou affair is a wake-up call: Canada needs to get serious about the China challenge, writes Richard Shimooka.

By Richard Shimooka, August 7, 2019

Buried under the headlines about the ongoing trade row between the United States and China, the flare-up of tensions in the South China Seas, and the Hong Kong demonstrations, the dispute between Canada and China continues to simmer underneath the surface.

Although tensions initially emerged over Canada’s detention of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver, it now affects nearly all aspects of the two countries’ bilateral relations, thanks to China’s decision to detain two Canadian citizens, Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig, on charges of stealing state secrets as well as imposing a ban on Canadian agricultural products. The dispute represents one of Canada’s most serious foreign policy challenge since 9/11. If there is a silver lining, it’s that Canadian policymakers and the public may find themselves in a situation to better understand the country’s global position and fully evaluate the international challenges on the horizon.

China’s actions come from a well-worn playbook, but one that Canada is unfamiliar with. In 2010, Japan detained a Chinese fishing boat captain after he rammed a Japanese coast guard vessel near the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. In response, China halted exports of rare earth metals to Japan and later held four Japanese contractors on suspicion of spying. Beijing only relented when Japan released the captain. Other countries, including India, Vietnam, South Korea, and the Philippines have experienced variations of this belligerent Chinese behavior.

Canada, however, is unfamiliar with these tactics, and is struggling to develop an effective policy response. Its position is complicated by the surprising unreliability of its closest ally, the United States. President Donald Trump’s pattern of undermining previously bedrock assumptions about American security, including US alliance guarantees, has caused severe angst within Canada. The situation has led some commentators, most notably former Prime Minister Jean Chrétien and former Ambassador to China John McCallum, to recommend that Canada should return Meng in order to de-escalate the conflict.

Their position follows a skeptical view of Canada-US relations. It also presents (in their minds) an opportunity for Canada to become a neutral broker between the two countries. The consequence of this position would be devastating to Canada and would represent a fundamental misunderstanding of the country’s position in the world. A failure to appreciate Canada’s strategic position, as an exceptionally close ally to the United States and an intrinsic part of the US-led Western alliance, is the very vehicle that the Chinese government has so far exploited. A reversal of the extradition order would be an unimaginable foreign policy coup, with significance far beyond that of Meng’s return. It would call into question Canada’s commitment to its closest ally at the very time it has provided the greatest dividend.

Of note, Canada’s willingness to continue the extradition process and endure the resulting economic consequences has only enhanced support in Washington, particularly in Congress and foreign policy communities. It has earned Ottawa both a reputation for being a steadfast ally and valuable political capital, which are clearly more important to Canada’s national interest than its relationship with China. This diverse support bodes well for long-term security and economic relations between the two countries, which will extend beyond the Trump administration’s term.

Unfortunately, the long view on Canada-US relations will have minimal effect on situation with China, especially with the present occupant of the White House. Ottawa’s response to Beijing should be measured, consistent, and firm. On the last point, the government’s approach has been lacking thus far. Given the statements from McCallum and Chrétien, the Liberal government must seize the moment by going beyond merely distancing themselves from the remarks and instead toughening Canada’s position. Otherwise, Beijing will be left to wrongly believe that Ottawa – and in particular, the ruling Liberal Party – may be close to acquiescing to their campaign of intimidation. Conversely, capitulating to Beijing’s demands would set an even more dangerous precedent for future relations with China. They would conclude that by applying enough coercive pressure, Canada would acquiesce to any demand. Finally, providing a clear rejection of the Huawei’s inclusion in Canadian 5G networks, a clear vulnerability to national security, would eliminate another potential lever the Chinese government could pull.

Canada’s diplomatic efforts must also avoid superficial efforts and move toward more meaningful measures. The Liberal Government has attempted to corral allies to pressure China over the detention of Canadian citizens. However, considering Beijing’s utter dismissal of criticism related to human rights abuses in Xinjiang, or its attitude toward the Hong Kong demonstrations, it is unlikely the campaign will force a change of policy. Furthermore, Canada’s allies have little incentive to do more than issue weakly worded demarches to China, as it is not a particularly strong or reliable ally for countries in the Indo-Pacific. Although Ottawa has slightly increased Canada’s military presence in the region and improved ties with Japan and Singapore, these are vastly insufficient to the challenge at hand.

Therefore Canada must continue to expand its diplomatic engagement and defence ties with key allies and partners. Not only will this shore up diplomatic support, it will send a solid signal to Beijing that its actions have real consequences. For example, Canada’s recent cross-servicing agreement with Japan represents a possible model that could be adopted elsewhere. It could also participate more actively in some of the joint infrastructure developments projects being led by Japan, the United States, and India. Such efforts could help facilitate greater Canadian engagement with the Quad – an informal security grouping that consists of the US, India, Japan, and Australia. It would also be a clear, but calibrated, response to China, communicating that further coercive efforts will only push Canada into closer relation with like-minded allies.

While the consequences of the Meng Wanzhou affair are serious and far-reaching, they provide Canadians a rare ability to re-focus our attention on China and Canadian foreign policy. It is clear that any pretense of neutrality has been eradicated, and Canada must start understanding and reacting to the geostrategic trends that will mark this century, or else be at their utter mercy. It is up to the public and policymakers to see if they heed these lessons.

Richard Shimooka is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Center for Advancing Canada’s Interests Abroad.