This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By Chris Alexander, July 10, 2023

When Henry Kissinger agrees it’s a good idea, it’s past time to make Ukraine a NATO ally.

Mr. Kissinger, the notorious great power realist who relegated Ukraine and other countries to Moscow’s “sphere of influence” for decades, has seen his misguided worldview blown apart by Belarus’s 2020 pro-democracy uprising and Ukraine’s wartime heroism since February, 2022.

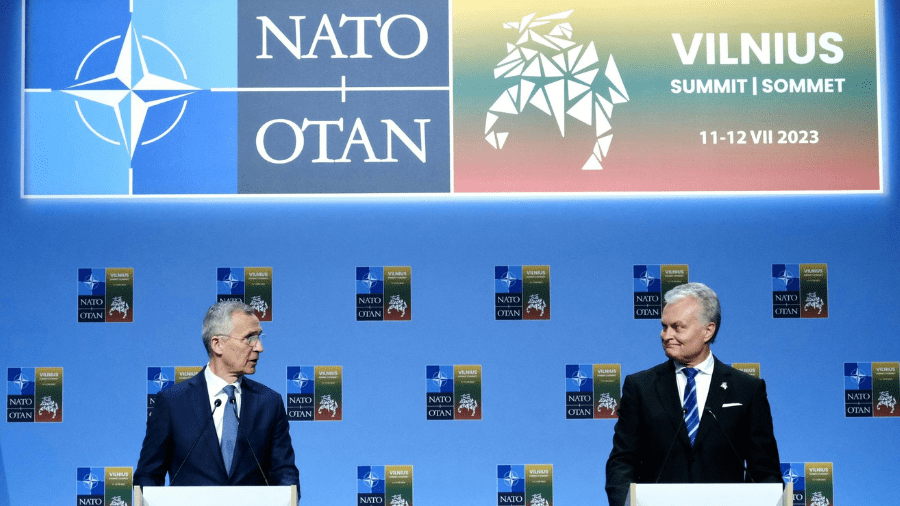

This week’s NATO summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, is a genuine opportunity to put right a historic string of strategic wrongs. When NATO leaders agreed 15 years ago in Bucharest that Ukraine and Georgia would become members of the alliance, then reneged, Moscow embarked on a spree of violence in Georgia, Syria, Ukraine and across Africa.

Allied inaction consigned Ukraine and Georgia to “grey zones” – a strategic limbo from which dictators and warlords drew strength.

Later, in 2008, Russia invaded Georgia. In 2010, Russia installed corrupt placeman Viktor Yanukovych as president of Ukraine. In 2011, Moscow propped up Syria’s genocidal dictator, Bashar al-Assad. In 2014, just as the Sochi Olympics were ending, Russia invaded Ukraine because Mr. Yanukovych had fled to Moscow after Kyiv’s Revolution of Dignity. It is simply wrong to imply, as former U.S. president Barack Obama did in a recent interview with CNN, that “a sense of Ukrainian identity separate from Russia” only emerged after 2014.

The origins of the name “Ukraine” date back to 1187, when it was first mentioned in the Kyiv Chronicle. This was centuries before “Muscovy” morphed into “Russia.” Crimea, Kyiv and the right bank of the Dnipro were only conquered in the late 18th century, and Ukraine’s struggle for independence resumed barely a century later with the proclamation of the Ukrainian People’s Republic on Nov. 20, 1917.

The Bolsheviks crushed this new state; Joseph Stalin inflicted the Holodomor on Ukraine and sought to eviscerate its cultural leadership during the Executed Renaissance – all precursors of Moscow’s genocidal agenda today.

When Stalin swivelled from being a Hitler co-conspirator to an ally of the U.K. (and later the U.S.) in 1941, Ukraine’s postwar fate was sealed. The dead letters of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, which offered Ukraine empty security guarantees, and the 2008 Bucharest summit declaration, with its empty NATO pledge, prolonged the agony.

Now, NATO can take three bold actions to ensure free Ukraine prevails: First, NATO should invite Ukraine to join the alliance – without a Membership Action Plan (as Finland has done and Sweden will soon do) – as soon as the war is won. Second, NATO allies should formally endorse Ukraine’s war aims – a total end to Russian occupation and full liberation – and the means to achieve this, which is collective self-defence, the principle underpinning NATO itself.

Third, NATO allies should provide the capabilities Ukraine needs to achieve victory as swiftly as possible, including the MGM-140 Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), a tactical ballistic missile; Taurus KEPD 350 air-launched cruise missiles; and dual-purpose improved conventional munitions (DPICMs) – now needed to clear Russian infantry from dug-in positions. NATO should also expedite the arrival of F-16 and other fighter aircraft – a combat capability that should have been provided much earlier.

Canada should send over 300 soon-to-be-decommissioned Coyote, Bison, and M113 light armoured vehicles (LAVs) and expand Operation UNIFIER to train Ukrainian forces on the territory of Ukraine, as Canada was doing from 2015 up to the end of 2021.

NATO itself should launch larger training, logistics, repair and supply missions to ensure Ukraine receives ammunition, weapons, parts and expertise as efficiently as possible. As Ukraine’s counter-offensive advances, NATO should undertake air defence and naval missions to protect liberated areas of Ukraine and restore freedom of navigation in the Black Sea.

We have been down these roads before. West Germany joined NATO in 1955 and Poland in 1999 over the objections of many doom- and nay-sayers. NATO took its air power out-of-area to Kosovo in 1999 and Afghanistan in 2003.

NATO’s actions will not only be decisive for the future of a free and democratic Ukraine, now fighting a true war of independence. They will also put Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and other states where Russia’s neo-colonial death grip lingers on paths toward European and Euro-Atlantic integration.

This summit is about a Europe free of dictators and a world where collective self-defence is upheld, with opportunities for free, democratic self determination multiplying. To get this result, NATO needs to invite Ukraine, already a brilliant fighting heavyweight ally, to the table; help Ukraine win a decisive victory over Russia’s war criminals; and field air, ground, logistics and naval missions that will end Russian aggression in Ukraine for good.

Chris Alexander is a former deputy head of mission of the Canadian embassy in Moscow and Canadian cabinet minister. He is currently a distinguished fellow of the Canadian International Council and the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.