This article originally appeared in the Financial Post. Below is an excerpt from the article.

By Jack Mintz, January 8, 2024

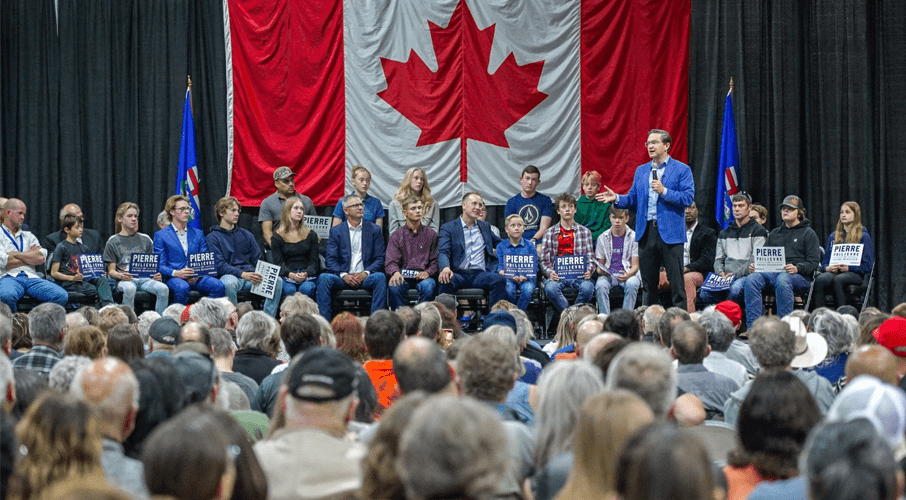

Following on this fall’s kerfuffle over Ottawa’s exemption of heating oil under the carbon tax, Opposition leader Pierre Poilievre has renewed his promise to “axe the tax.” In response, the government is reminding voters that 90 per cent of what it earns from the tax is disbursed as lump-sum rebates of equal value to each household, rich or poor. And it claims these rebates make the average resident better off in the eight provinces where the federal tax applies. (B.C. and Quebec have their own carbon pricing systems.)

But is it true that axing the tax necessarily means axing the rebates?

I have always argued that the carbon tax is better policy than the existing pancake approach, which stacks one inefficient, soak-the-poor carbon mandate, regulation and subsidy on top of another until even the relevant ministers forget how many anti-carbon initiatives we have. On the other hand, if our largest trading partner, the U.S., isn’t going to price carbon, maybe axing the tax makes sense. But if we do that, do the rebates have to go, too?

Analysis does typically assume rebates go hand-in-hand with the carbon tax. And if you look only at the tax and the rebates, Ottawa is probably right: the rebates in large part offset the tax. But Poilievre takes a broader view. He cites a 2022 Parliamentary Budget Office study that also looked at the effects of the carbon tax on household incomes as a result of economic restructuring. It gives different results. For example, it estimates that for the average Ontario household the fiscal “cost” — carbon taxes and related GST effects net of rebates — is actually a net gain of $113 by 2030-31. But add in the likely economic effects on employment and investment income and that gain turns into a net loss of $1,145 in 2030-31.

***TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE, VISIT THE FINANCIAL POST HERE***