Asian arms exports have a growing role in the global and regional arms market, particularly China and Japan, writes Lucie Béraud-Sudreau.

Asian arms exports have a growing role in the global and regional arms market, particularly China and Japan, writes Lucie Béraud-Sudreau.

This post is based on the work of the recently released Military Balance – the annual assessment of global military capabilities and defence economics published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

By Lucie Béraud-Sudreau, March 29, 2018

In late January 2018, the Australian Ministry of Defence unveiled a ‘Defence Export Strategy’, intended to propel the country into the world’s top-ten arms exporters by 2028. To this end, the government will set up new arms-export support instruments, similar to those put in place by traditional arms-exporting states, including a dedicated export-support agency and loans for defence-industrial groups wishing to increase foreign sales. Despite these new tools, rising to the top-ten of global arms exporters is an ambitious goal, and it is unlikely that Australia can reach it in the given period.

Indeed, today’s major arms suppliers rely on large defence technological and industrial bases (DTIBs) and equally large domestic markets: this is the case for China, Russia and the United States, the world’s largest arms exporters. Second-tier arms exporters, such as Western European states like France and Italy, among others, for their part, rely on decades spent developing and sustaining local DTIBs, enabled by significant investments, including in long-term research and development.

The new Australian export strategy reflects an increasingly evident trend in Asia, where states are developing their domestic arms industries and increasingly participating in the global arms market. As part of this, China and Japan have begun competing to gain regional influence through arms transfers, a process that has accelerated since Japan’s relaxation in 2014 of its self-imposed ban on arms exports. However, Tokyo’s difficulty in carving a place for itself in the global and regional arms trade (for example, losing out to France’s DCNS in Australia’s submarine-procurement competition) should be a warning for Canberra; all the more so that Japan relies on an already strong DTIB, which Australia is lacking.

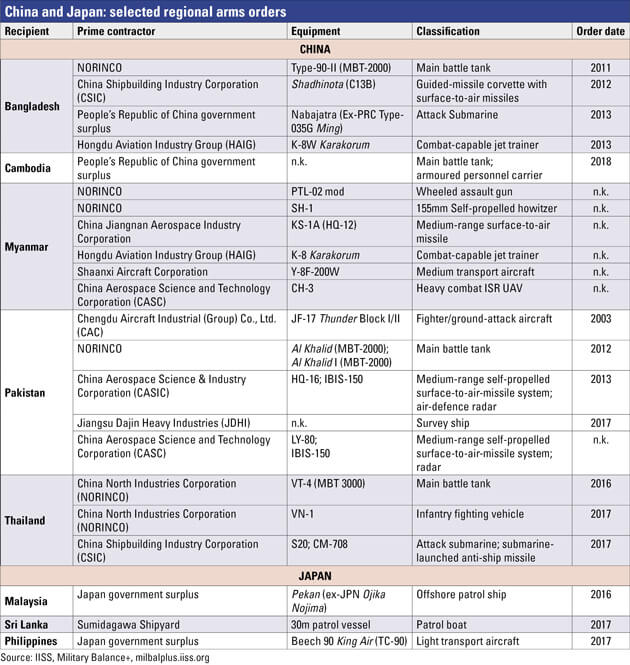

This Sino-Japanese competition can be observed in Malaysia, to whom Japan offered retired Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion maritime-patrol aircraft, whilst China agreed to supply littoral mission ships, to be built in Malaysia. Meanwhile, China donated 3,000 assault rifles to the Philippines and Japan agreed to provide parts for the Philippines’ Bell UH-1 utility helicopters, having already supplied second-hand Beechcraft TC-90 King Air aircraft and vessels for the coastguard.

In Thailand, China has long cooperated with the Defence Technology Institute on multiple-launch rocket systems. More recently, Bangkok ordered 28 VT-4 main battle tanks from China, with a first batch delivered in October 2017, and an attack submarine was ordered from China in May the same year. However, Japan is only at the stage of negotiating a defence trade and technology agreement with Thailand.

In Vietnam, where it is not competing with Chinese influence, Japan provided six second-hand patrol vessels in 2014 and offered six more in early 2017. Tokyo has also pledged military aid worth US$500 million to Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam and the Philippines, over the period 2017–19. Further south, Japan is also looking to strengthen ties with Indonesia and India, notably with the potential sale of US-2i amphibious search-and-rescue aircraft. However, as shown in the table below, China is significantly ahead of Japan in terms of regional arms exports.

Beyond this developing Sino-Japanese rivalry, other Asian arms exporters are rising in the global and regional arms market. This is notably the case for South Korea, for whom, in 2017, arms exports totalled US$3.2 billion – a 25 percent increase on 2016 sales. Still at an earlier stage in the development of its arms-export policy, Indonesia is also looking to increase its arms sales, in the region and beyond. Indonesian companies have won contracts in various Asian states: in 2014, the Philippines placed an order for two landing platform docks with the shipbuilding company PT PAL and in 2017 Nepal signed with PT DI for the supply of one CN-235M light transport aircraft, to be delivered before the end of 2018. Beyond Asia, Indonesian firms are also looking to gain market shares in Africa, Europe and the Middle East. For example, PT DI agreed the sale of a CN-235 with Senegal in 2014.

While Australia’s goal to reach the top-ten of arms exporters in the next decade appears unachievable, these examples show that if the political leadership of a country chooses to prioritise the defence industry, for example South Korea, which has become a major arms exporter, significant results can be achieved. However, Japan’s recent attempts to penetrate the global arms trade reveal that a technologically advanced DTIB is not enough.

More broadly, Australia’s ambitious objective reflects the region’s increasing determination to limit the reliance on foreign defence-equipment suppliers, as well as to reap more economic benefits from the large investments in defence by Asian states in recent years.

Lucie Béraud-Sudreau is Research Fellow for Defence Economics and Procurement at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.