![]()

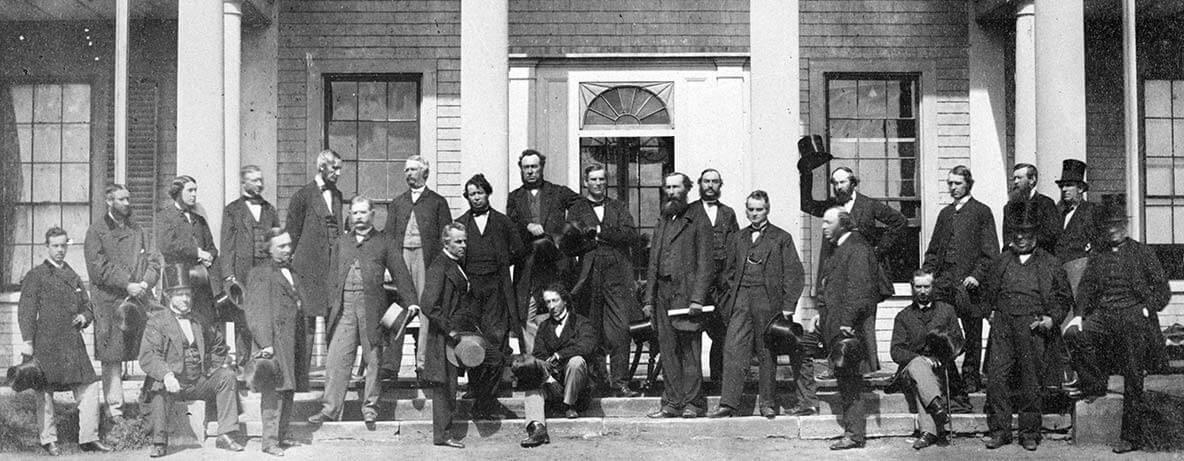

Delivered shortly after the Quebec Conference of October 1864, Alexander Galt presents the coalition government’s comprehensive official case in favour of Confederation. The honour likely fell to Galt in recognition of his leading role as an advocate for Canadian federalism, having introduced federalist resolutions to the Canadian legislature in 1858, and later that year joining the Cartier-Macdonald government when it adopted federation as official government policy. Galt authored the key federation dispatch of 1858, in which the Canadian government admitted the urgent need for Constitutional change, and in which a proposed division of powers was set out, largely similar to the one adopted in 1867.

One striking aspect of Galt’s speech is his particular concern for minority rights, as the chief representative of the English-speaking minority of Quebec. Warning that no measure could be approved by Canadians not founded in equal justice, Galt outlines protections to be granted for minority education rights. He appeals to the shared interests of French and English-speaking Canadians in the developments of their common country, arguing that Confederation will benefit all Lower Canada – “not French Lower Canada, or British Lower Canada – but the whole of Lower Canada.”

The following is an extract. Alexander Tilloch Galt’s full Speech can be downloaded here.

MR. GALT, who, on rising, was received with great applause, addressed the Chairman and said the practice bad obtained in England of late years for the leading politicians and those charged with the administration of the Government to meet their constituents and the public during the recess of Parliament, and discuss with them the questions then occupying the public mind. He believed that great advantage had arisen from the practice of instructing the public with reference to the questions then before it, from the fact that, when Parliament afterwards met, it had the intelligent ideas of the people brought to bear upon its deliberations.

If ever there was an occasion upon which he might wish to address his constituents, it was now, when they had before them a measure calculated not merely to change their present position, but through that change to raise this country to a scale of greatness which we had longed for, but had not hitherto had the prospect of attaining. That measure was one which had created a good deal of feeling in the mind of the people at large; and, knowing that to be the case, he was sure he was in the line of his duty in coming before them that day, and endeavouring to give them some of the reasons why the measure of confederation for the British North American Provinces was now submitted to the consideration of the people of Canada.

No measure could possibly meet the approval of the people of Canada which contained within it the germs of injustice to any.

He might say that with reference to this particular subject he felt a double responsibility resting upon him. He not only felt the responsibility common to all who represented constituencies in Parliament, but he had also upon him the responsibility of acting as the representative of a class in Canada— of a minority in Lower Canada— and of endeavouring to see, in the measures which were proposed, that justice was done to them in common with all classes of the community. No measure could possibly meet the approval of the people of Canada which contained within it the germs of injustice to any; and if, in the measure which was now before the people of Canada, there was anything which bore on its face injustice, it would operate greatly against the success of the measure itself.

Defects of the Present Union

He would ask the permission of the meeting for a few moments before entering on the plan of Confederation, to recur to the events which bad rendered it necessary to bring before the people of Canada a measure for the alteration of their constitution. And with that view he might perhaps be allowed to refer briefly to the circumstances under which the union of the two Canadas took place and the political action which had taken place under that union. (Hear hear.)

The inherent defect in the Imperial Act for the Union of the two Canadas was this: it attempted to combine the federal principle with unity of action.

The Union of Canada was an act of Imperial policy not sought for by the people of Lower Canada at all events. It was adopted by the Imperial Legislature with the view of remedying difficulties which then existed between the two Provinces. The inherent defect in the Imperial Act for the Union of the two Canadas was this: it attempted to combine the federal principle with unity of action. It endeavoured to give equal representation to the two sections of the Province, while it brought them together for the purpose of dealing as one with all subjects both general and local.

So long as there was no very great difference in the population of the two Canadas — so long as they contributed in somewhat equal proportion in the expenditure — the system worked well, but when the fertile lands of the West attracted emigration in greater numbers to Upper than to Lower Canada; when the wealth and population of that section increased in a greater ratio than it did below, then the difficulties which were inherent in the Act of Union began to appear; then began to rise the claim that in Upper Canada there was taxation without representation, while the resistance which was made from Lower Canada arose from the feeling that if increased representation was given it would be not simply an interference with the mere representation in Parliament, but would affect the whole principle upon which the Union Act had been based.

Alexander Tilloch Galt’s full Speech can be downloaded here.