This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Alexander Dalziel, February 23, 2024

After two years of a Russia-initiated war that has killed thousands of Ukrainian civilians and soldiers, upset world order, worsened inflation, and cost millions of taxpayer dollars, Canadians are getting a little tired of the Ukraine-Russia conflict, polling shows. But now is not the time to lose focus.

The February 24 anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Ukrainians’ inspiring resistance is an opportunity to reassess and reaffirm the importance of Canada’s commitment to Ukraine—and a more secure Canada.

The House of Commons agreed to update a free-trade agreement with Ukraine on February 6, but, unusually, the Conservative Party opposed it, claiming not to support some of the environmental provisions it contained. That vote was taken as Canadians from across the political spectrum are feeling less inclined to support Ukraine, according to a recent Angus Reid poll.

The number of those polled who said Canada is doing too much has almost doubled to 25 percent, particularly among Conservative voters. Interest overall is waning, as only 45 percent say they are closely following the conflict in the news, down from 66 percent in May 2022.

But after two years, we should pay attention, because support for Ukraine is as important as ever, even if events elsewhere threaten to shift our attention. The conflict is but one part of an increasingly turbulent global picture, extending from a combusting Middle East to Serbia interfering with its Balkan neighbours to Azerbaijan ejecting its entire Armenian population. Insecurity abounds in parts of Africa and South America. The Economist Intelligence Unit tells us democracy is doing poorly worldwide. Atop this, U.S.-China tensions sit unresolved.

Most significantly, China and Russia are creating a colossal geopolitical bloc in Eurasia with daunting fundamentals in natural resources, technology, and industrial capacity. The authoritarian dynamic evolving between them is now closer together than ever. They have a shared interest in pushing back the United States and its allies—that is, Canada and our allies—so they can have a free hand in neighbouring countries.

The conflict in Ukraine represents a pivotal arena, and, if left unchecked, that dynamic will have three key implications for the West and Canada. First, an abandoned Ukraine would destabilize Europe. Anyone saying Russia’s ambitions end at Ukraine’s western borders is, at the very least, overconfident. Moscow openly stated in 2021 that it wanted NATO rolled back in Europe. The tensions unleashed even if Russia “only” occupied all of Ukraine would cause the most severe deterioration in European security since the early Cold War. The surest way to keep Canada and NATO out of a broader war with Russia, not get into one, is to support Ukraine.

Second, a Russian victory in Ukraine imperils Canadian interests in the Indo-Pacific region. Since 2022, we have seen China’s aggressiveness towards Taiwan mount. A flagging commitment to Ukraine tells the Communist Party of China a lot about the reserves of fortitude—or lack thereof—of Taiwan’s foreign supporters, should it invade the island. That increases the likelihood of an armed China-U.S. confrontation—and an interruption to the supply of computer chips our economy depends on given that most are manufactured in Taiwan.

Third, Russia and China are enjoying unprecedented cooperation in the Arctic. While to date this is mostly economic, two authoritarian governments projecting influence in the Arctic corrodes Canada’s regional governance. Russia already has the world’s largest icebreaker fleet; China, a non-Arctic state, is on course to have almost as many polar-class heavy icebreakers as Canada and the U.S. combined. Conceding Russia’s imperialism in Ukraine is unlikely to encourage Moscow to abide by international law when it comes time to settle maritime boundaries with Canada in the Arctic Ocean.

To protect Canadian security and prosperity amid this flux, Canada will need partners.

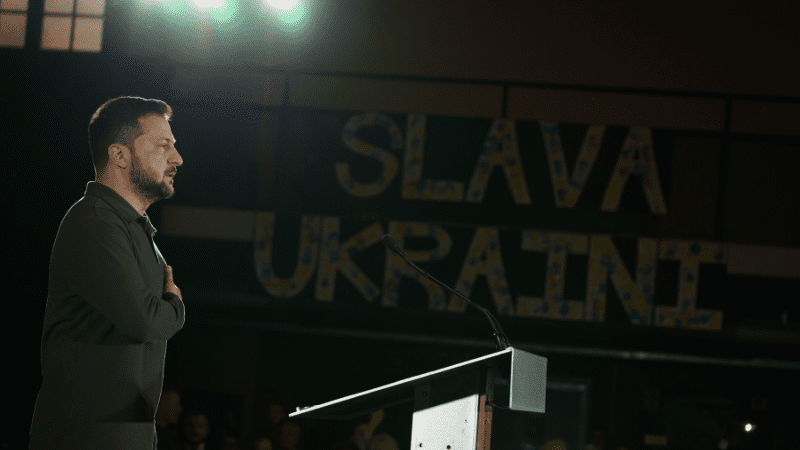

Seen in this light, Ukraine is a good investment. Its political fundamentals are strengthening. Elections there are real. It has a flourishing civil society fighting for—and achieving—transparency and accountability to dismantle corruption, including in the military. Ukrainians openly criticize President Volodymyr Zelenskyy during a war. (In Russia, even calling it a war lands you in jail.) That speaks to basic political rights that Ukrainians have won and do not take for granted.

Compare that to Russia, where the leading opposition figure of the last decade, Alexei Navalny, died in mysterious circumstances at 47 years old in a penal colony last week. He had already survived several attempts on his life and health. Keep in mind that we hear about corruption in Ukraine because the media actually reports it there. In Russia, President Vladimir Putin has destroyed the media to prevent such exposure. And, by the way, he will be re-elected for another six years in sham polls next month. The threat is not going away.

On the battlefield, Ukraine needs immediate help. It is fighting hard. For instance, without a navy of its own, it is regularly sinking Russian warships, allowing grain to reach Africa and the Middle East, bringing down food prices, and tackling a key component of inflation. But it is under pressure, badly outnumbered by Russian forces, and, undersupplied by its foreign supporters, slowly conceding ground on some fronts and holding the line in others, all at great cost to Russian forces. Russia’s economy is on a war footing; North Korea’s artillery shell production for Russia is out-competing the collective military-industrial capacity of NATO.

Regardless of future U.S. choices, we have committed European partners. Europe’s monetary, material, and political commitments to Ukraine are large. Cooperation with NATO and European Union allies defrays the financial costs. Enhanced Canada-Europe cooperation on defence production, for instance, would produce the armaments and technologies that Ukraine (and Canada and Europe) require.

If Canadians’ enthusiasm for Ukraine is flagging because of money alone, we should reconsider the cost in the world as it is, not as it was or as we wish it to be. Defending our security and prosperity is going to get much more expensive, regardless of what we choose to do in Ukraine. That is an inconvenient fact for all of Canada’s political parties.

Our politicians—and let’s be honest, we Canadians—have so internalized the idea that we can free-ride on the Americans for security that we indulge the belief that our politics consists of domestic issues only, such as cutting taxes or spending on social programs. But foreign policy is the other side of the statehood coin. To be a country, you have to have both. We have forgotten that over the last 30 years. Internecine debates about day-to-day politics are well and good, but they cannot become our sole obsession. Whether we like it or not, Canada’s interests are tied up in what happens abroad. If we want to have politics for the Left, Right, and Centre at home, then doing all we can to support Ukraine’s cause is fundamentally the right choice.

Alexander Dalziel is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa.