By Paweł Markiewicz, August 10, 2023

Besides testing the resolve of the world’s defenders of democracy, the war in Ukraine has also been a wakeup call about the poor state of military capabilities among some NATO allies.

During a meeting of Russia’s Security Council last month, President Vladimir Putin delivered a tirade when presented with information that Poland has purportedly come to terms with the fact that Ukraine is on the verge of defeat.

He alluded to Warsaw allegedly preparing to deploy “a well-organized, equipped regular military unit” to western Ukraine with the goal of “subsequently occupying” territory that in the past fell within Poland’s borders. Besides claiming that Polish forces would “stay there [i.e. in Ukraine] for good,” he also cited Belarus, insinuating how “they [Warsaw] dream of Belarusian land”, before sternly warning that any aggression against Russia’s ally in Minsk would merit a military response.

While those in the West may be tired of hearing Putin’s invocations to the past, historical politics is a potent tool that shapes Russian ideology and helps legitimize the Russkiy mir or ‘Russian world’ concept driving, among other initiatives, Moscow’s war in Ukraine. The message to be taken from this latest diatribe is that he won’t relent hostile actions toward NATO countries, especially those closest to Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, where a significant number of Alliance forces (e.g. U.S., Canadian, and British) are currently stationed.

Putin’s monologue came days after NATO partners had converged on the alliance’s eastern flank in Vilnius, Lithuania for their annual summit, seeking to maintain political and military cohesion for Ukraine while bolstering defence plans and deterrence capabilities to offset potential large-scale threats from Russia.

The summit addressed a weighty topic on the minds of experts and decision makers alike – Ukraine’s future as a NATO member. Although ultimately deciding not to invite Ukraine to join, NATO nonetheless moved the needle beyond its broad declarations on this question back in 2008. They agreed to forego the Membership Action Plan process necessary to receive a formal invitation to join NATO, increasing Kyiv’s chances for membership in the near future. Creating a NATO-Ukraine Council gives Kyiv added means for permanent and regular consultations on the same terms as existing members, allowing it to influence new forms of cooperation with NATO and exert pressure on its admission. However, the political process toward reaching a consensus — which included Ukrainian officials using the summit to publicly pressure the alliance for an invitation to join, and members adopting a mild declaration — showed that fissures exist in NATO when it comes to questions of when to admit Ukraine.

At Vilnius, NATO allies addressed several other pressing issues. For the first time since the end of the Cold War they accepted defence plans specifying that the alliance will respond to future attacks with at least 300,000 troops.

Approved regional plans mean that NATO will prepare to fend off Russian threats, including in the north Atlantic and northern Europe; the decision to let Sweden join the alliance will tremendously benefit defence and deterrence capabilities in this region and in the Baltic Sea area. Finally, addressing one of the most pressing challenges facing allies in the wake of Russian military aggression, i.e. the need for significant key defence investments, NATO members committed to spending a minimum of 2 percent of their GDP on defence – making it a threshold, not a ceiling. This will force many allies to take collective defence more seriously.

Coupled with Russia’s renewed aggression in Ukraine (during the summit, Kyiv came under rocket attack for the second time in July), a series of additional regional political and security challenges laid down by Putin indicated that NATO will have even more to prepare for in the near future.

First was Putin’s plan, announced last March, to place Russian nuclear warheads in Belarus – an agreement that Belarusian strongman Aleksander Lukashenka signed onto on May 25. The first weapons deliveries reached Belarus most likely around mid-June.

Second was the short-lived military revolt by the private Wagner Group company, revealing an apparent growing internal crisis within certain levels of Russian power. It ultimately resulted in the redeployment of Wagner mercenaries to Belarus (sources indicate from 2,000 up to 10,000). During a meeting with Putin on July 23, Lukashenka mentioned that the Wagner troops in Belarus want to go “on a trip to Warsaw” – a veiled threat against Poland, NATO, and the West in general.

Decisions by NATO leaders at the Vilnius summit will go a long way in restoring the alliance to its fundamental role of containing and deterring Russian aggression. Even as political declarations move Ukraine closer to NATO membership, the awkward steps to reaching them reinforce some of Putin’s assumptions about the West. He correlates the NATO allies’ lack of consensus about a definitive timeframe for Ukraine’s membership (leaving it in a ‘waiting room’ status) as a sign of deep divisions between Alliance members, cracks that he will continue exploiting in order to break the West’s resolve for Kyiv.

Allies also missed an opportunity to publicly roll back military self-restraints contained in the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, in which they agreed to not permanently deploy substantial combat forces (understood as more than one brigade) in new member states on NATO’s eastern flank. Although defence plans approved at Vilnius – which include reaffirming commitments to increase eastern-flank battlegroups to brigade size units “where and when required” – will help the alliance address large-scale threats if Russia chooses to attack NATO, Putin will likely maintain his view that any lingering forms of self-restraint represent weakness. This will embolden him to further escalate tensions, for example by deploying nuclear weapons in Belarus or to a region where NATO is increasing its defence capabilities, like the Arctic. He’ll also uphold his view that, without NATO troops permanently stationed on the eastern flank, members there (e.g. Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia) remain a “grey zone” that can be gambled away by the West, opening a door for Russia to once again expand its influence in eastern Europe.

Moves by Putin to increase military posturing, like turning Belarus into a “Fort Russia”, signal that he now has a multifaceted set of options for escalating threats against the West. Should Russia escalate its threat via Belarus, NATO would likely be forced to rethink its response plans on defending the eastern flank. This will include putting forces on alert for potential military exercises close to NATO borders between Russian, Belarusian, and Wagner forces. Given this possibility, Poland preemptively moved military units to areas along its border with Belarus. Mindful of how Belarus tested NATO readiness by launching the hybrid border crisis in 2021 against Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, the alliance must be prepared to respond to similar hybrid- or cyber-attacks in its eastern neighborhood. If NATO considers increasing its troops on the eastern flank near Belarus (i.e. in Poland, Latvia and Lithuania), it will need to revisit its nuclear policy toward Russia to counter what will likely be Putin’s brinkmanship threats stemming from Russia’s nuclear weapons in Belarus. It’s unlikely that they will be removed in the near future, enabling Putin to use them as a bargaining chip in possible negotiations over Ukraine.

Barring a historic Russian defeat, or internal political crisis forcing a cessation of hostilities and regrouping scenario, Putin will keep testing NATO resolve toward defending ‘every inch’ of alliance territory.

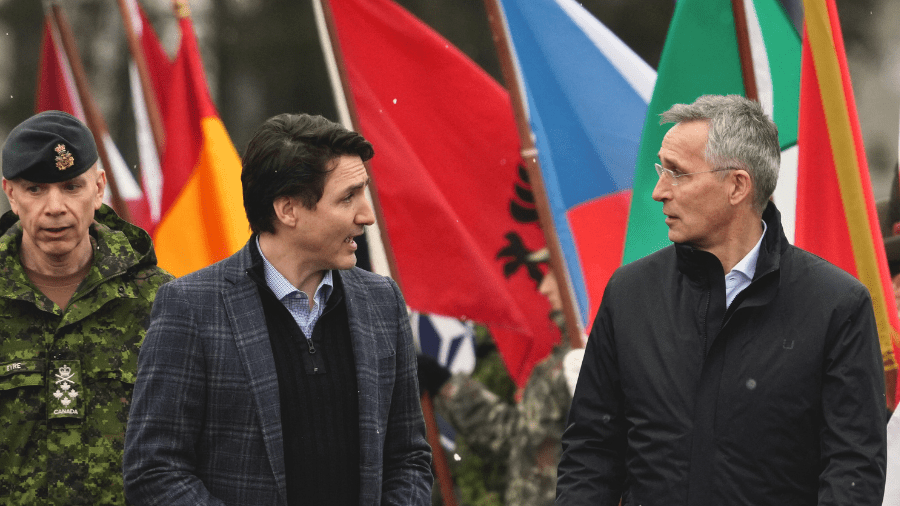

Canada has since 2017 played a lead role in NATO’s multinational enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) battle group in Latvia, making it a frontline alliance member, and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently said Canada will be increasing its presence there with a tank squadron.

Ottawa has been one of Ukraine’s most vocal supporters, sending important military supplies (most notably eight Leopard-2 battle tanks), assisting in humanitarian efforts for refugees temporarily settling in Poland, and expediting visa processing for those seeking refuge in Canada (about 175,000 to date). Canada has provided over $8-billion in direct assistance to Ukraine since Russia’s invasion in February 2022. As well, Trudeau committed to continue Canada’s role in training Ukrainian security service and military personnel through Operation Unifier – the effectiveness of which is being proven on the real world battlefield – and has joined the effort to train the Ukrainian Air Force to operate and maintain Western fighter jets.

Good intentions notwithstanding, and given the under-resourced state of its own armed forces, Canada may have hit a ceiling on what more it can offer Ukraine, or how it would bolster its eFP battle group in Latvia to keep commitments around increasing it to a brigade size level.

NATO members’ concerns about the scale of Russian aggression (Canadian forces in Latvia have been the target of Russian hybrid attacks in the past and will likely be again), combined with agreements made at Vilnius about defence obligations, have put Canada at the centre of some post-summit fallout, focused on Ottawa’s record as a laggard in defence spending. As a frontline, but non-European NATO member Canada spends much less (about 1.3 % of its GDP) than, for example, its Central East European partners.

Canada, like many of its partners, must do its homework (i.e. by publishing a blunt and honest defence review) in order to make tough but necessary political decisions on spending real dollars on defence.

Next year’s NATO summit in Washington D.C. will mark the 75th anniversary of the alliance’s creation and its core commitment to defending its members and deterring aggression in its neighborhood. While it would be fitting to see a victorious Ukraine join the Alliance at that occasion, what’s more likely is that the alliance will face further challenges to its cohesion and defence posturing in Europe. This summer in Vilnius, NATO allies made it clear they stand with Ukraine now and for years to come. However, its commitments to defence and deterrence will face serious near and long term pressure. Putin knows his war of aggression is not just about Ukraine’s independence and the place of freedom in Europe, but also about Russia’s imperial future – something he’s willing to keep raising the stakes on to uphold.

Paweł Markiewicz is a Historian and the executive director of the Washington D.C. Office of the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), specializing in topics concerning Poland’s transatlantic relations as well as US and Canadian foreign-domestic policy.

This article was written with support from Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS).