This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By Aurel Braun, June 28, 2023

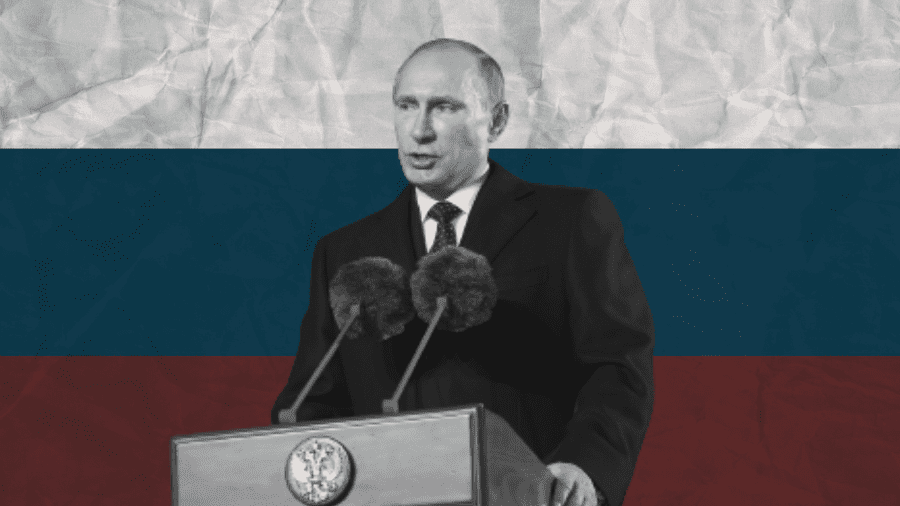

Bucha, Irpin and Mariupol, among others, have been indelibly etched into the history of horrendous war crimes committed by Russia against Ukraine. Vladimir Putin’s regime is responsible for Ukraine’s ordeal, but Yevgeny Prigozhin and the Wagner Group’s rebellion also starkly illuminates that this regime is also the bane of the Russian people.

By publicly challenging the Russian narrative – calling Mr. Putin’s “special military operation” a war, denouncing the justification and military conduct, and deploring the huge losses of Russian soldiers – he went beyond confronting the Russian military leadership (and indirectly criticized Mr. Putin). He highlighted, perhaps unwittingly, the sordid character of Mr. Putin’s 23-year-old regime that has failed the Russian people in manifold fundamental ways.

The mutiny was short, ending with a compromise agreement where Mr. Prigozhin is to go into exile in Belarus and the Russian government dropped all charges against him and the members of his Wagner mercenaries, despite Mr. Putin’s accusation of treason. However, this does not mean that the damage to the Russian regime will not be grave and long-lasting. The significance of Mr. Putin’s concession cannot be overstated, and the implications, ironically, may be best understood through the lens of The Sopranos TV show or The Godfather films rather than strategy theorists such as Clausewitz and Machiavelli. This is because Russia is not run like a normal state and decision-making is conducted more along the lines of an organized crime syndicate, where any weakness, including compromise, by the head can ultimately prove fatal.

In this system Mr. Putin pitted one faction against another, favouring and punishing, as the unchallenged balancer and decider. All this has depended on absolute power, and the perception of invincibility. That aura has been punctured as Mr. Putin had to compromise and Mr. Prigozhin appears to survive.

On the political level, in the syndicate system, power is prime. Significant reform is deemed risky and everything else is instrumental to keeping the leader in power. In Russia this has meant diverting public attention away from fundamental problems rather than reform, where foreign “successes” distract from domestic failures.

Consequently, Russia’s all-out war against Ukraine was no mere miscalculation. Domestic repression foreshadowed external aggression. Though the war may have had nationalistic and imperial colorations, in essence it was Mr. Putin’s ultimate diversionary tactic. A quick conquest would reinforce his rule and also prevent the possibility of democratic contamination from a future successful Ukraine.

Russia’s failure to swiftly prevail and Mr. Prigozhin’s insurrection also reveal the overall bankruptcy of Mr. Putin’s regime and the terrible opportunity costs. Despite some pockets of excellence, Russia, a country with unparalleled natural resources and remarkable human talent, has not succeeded in creating a modern state that is resilient and economically competitive. Corrosive corruption has permeated its military. Russians, on a per capita basis, are poorer than Romanians, suffer from a stagnant and inflexible economy and now face myriad, escalating Western sanctions that restrict access to vital technology and investments, deny travel and put at risk Russian overseas funds and assets.

Further, Russia’s war in Ukraine has backfired in two major ways that clearly illustrate Russia’s growing international weakness rather than support Mr. Putin’s claim to promote Russian security and international influence. First, the invasion of Ukraine so acutely threatened European states, that not only have NATO members grown closer, with many significantly increasing defence spending, but crucially, two neutral states that had been remarkably accommodating to Russia, Sweden and Finland, decided to join the Alliance. Finland, with a 1,340 km border with Russia, is now a member and Sweden is likely to be one soon, representing a tectonic strategic shift that must be a nightmare for Kremlin strategic planners.

Second, the uneasy historical relationship that Moscow had with Beijing, which combined caution and co-operation, has now become one of surging Russian dependence. It is not only an asymmetrical economic relationship, given China’s vastly larger, diversified economy, but one where Russia is the supplicant in desperate need of international political support from Beijing. Rather than being a partner, Russia is well on the way to becoming a Chinese vassal state.

In short, Mr. Putin has mortgaged his country’s future and wasted its resources in order to maintain absolute personal power. The damage that he has done to Russia far outweighs any benefits. The Kremlin’s wanton aggression in Ukraine and Mr. Prigozhin’s mutiny have peeled away some layers of the regime’s camouflage to reveal that although Mr. Putin certainly has been a terrible tragedy for Ukraine, he has also been a disaster for Russia.

Aurel Braun is a professor of political science and international relations at the University of Toronto and an associate at Harvard University’s Davis Center.