This article originally appeared in the Financial Post. Below is an excerpt from the article, which can be read in full here.

By Philip Cross, November 18, 2022

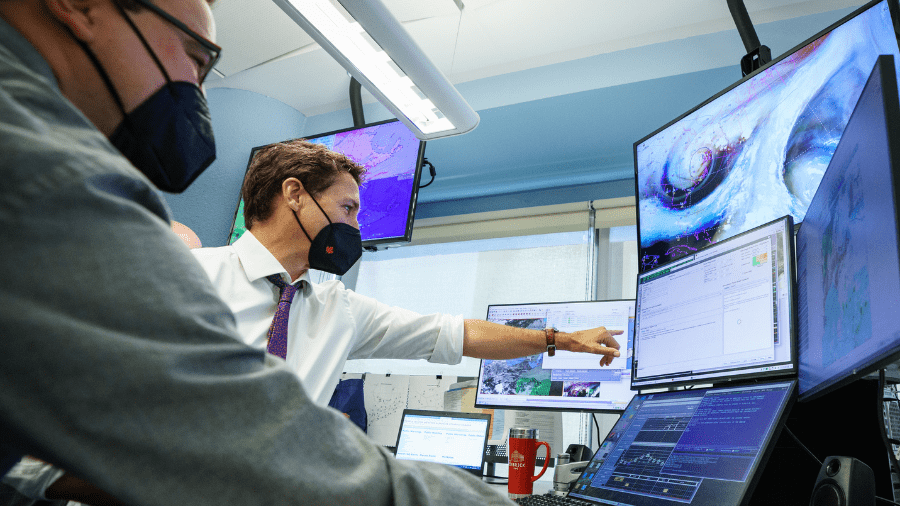

Prime Minister Trudeau recently questioned the viability of exporting liquified natural gas from Canada’s East Coast to Europe, saying there has “never been a strong business case” for such projects — even as natural gas prices soared in a Europe weaning itself from Russian supplies. Trudeau’s background is in teaching, not business, so I doubt he knows much about evaluating business cases. But we citizens can discern the business model he evidently favours based on how his government has operated for the last seven years.

Since its election the Trudeau government’s strategy has been to ramp up spending and finance it with a steady string of budget deficits issued at low interest rates as it waits — probably vainly — for its various “investments” in human capital and green energy to generate future revenues. Government program spending rose rapidly even before the pandemic, from 12.5 per cent of GDP when Trudeau took power to 14.6 per cent in 2020 and then, according to this month’s fiscal update, to 15.7 per cent in 2022-23. Over half this increase was debt-financed, as revenues rose only from 14.7 per cent of GDP in 2015-16 to 16.0 percent in 2022-23. This debt-based strategy assumed that: interest rates would stay low, willing investors could be found once the Bank of Canada stopped buying the government’s debt and future revenues would materialize. This is a risky plan for an economy built on highly cyclical industries such as housing, autos, technology and natural resources.

Mr. Trudeau’s financial strategy most closely resembles the Silicon Valley model, as outlined by Alexandre Lazarow, venture capitalist and adjunct professor of entrepreneurship at the Middlebury Institute in Monterey, in his book Out-Innovate: How Global Entrepreneurs from Delhi to Detroit Are Rewriting the Rules of Silicon Valley. The Silicon Valley model of startups requires venture capital investment up front and regular injections of cash as firms struggle to cross the so-called “valley of death,” in which their costs outstrip their revenues. A few tech firms achieve the status of unicorn, with their valuation growing to $1 billion or more, but 70 per cent fail before generating sufficient profits and many more fail afterwards according to Lazarow.

***TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE, VISIT THE FINANCIAL POST HERE***