This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, June 10, 2022

The Shangri-La Dialogue is normally an annual conference held in Singapore. It is meant to bring together countries in the region to discuss the critical security issues that challenge the region’s cohesiveness, peace and stability.

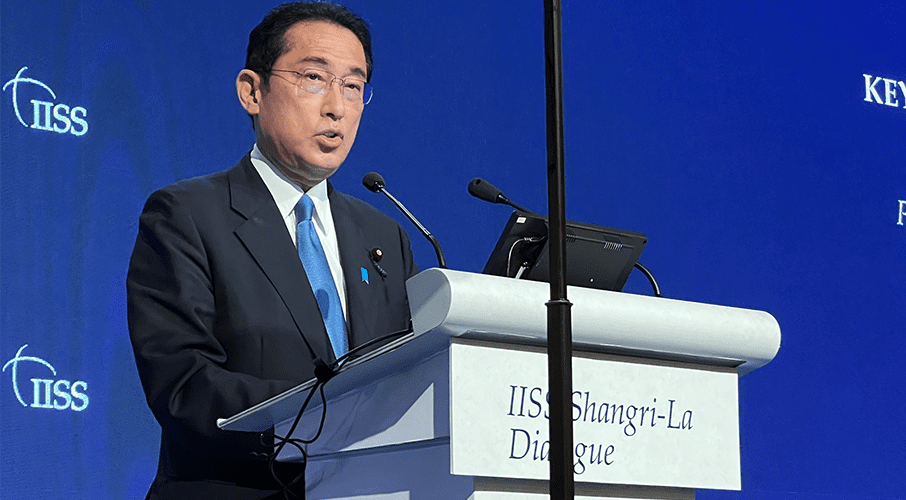

This year, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida will give the keynote address. It will be followed by China’s minister of national defense, Wei Fenghe, from the People’s Liberation Army and U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin.

Kishida and Wei will portray two very different Indo-Pacific regions. Wei will stress that the Indo-Pacific region is a geopolitical concept designed by the U.S. and the West to contain China’s rise. He will underscore that the Asia- Pacific region (China does not accept the Indo-Pacific framing) has been destabilized by a cold war mentality, small cliques of nations forming alliances targeted at China and efforts by undisclosed countries (read the U.S. and Japan) challenging Beijing’s One-China policy.

The general will paint a picture of a victimized China, surrounded by U.S. military bases, and by a United States that is interested in exporting its political system, its values and its norms. He will link the security challenges that China has faced in Xinjiang province, Hong Kong and across the Taiwan Straits as being spearheaded by outside powers in an effort to delegitimize and destabilize his country’s political system with the intention to remove the Chinese Communist Party.

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, AUKUS and NATO, especially the united front to push back against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, will be given as evidence that the West is not willing to accept responsibility for Moscow taking defensive actions against an expansionist West. He will suggest that the West is not willing to accept the notion of a multipolar world in which non-Western powers and their values are not the primary arbiter of international relations.

These views are certainly not singular, but only a handful of states in the Indo-Pacific region, including North Korea, Russia and Iran, would see the region in such a way.

Kishida in contrast, will talk about a region that is being challenged by revisionist powers that want to overturn a rules-based order. The key examples will include gray-zone operations and lawfare tactics in the East and South China Sea and threats to the peace and stability across that Taiwan Straits.

Key areas of focus will include Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and how Vladimir Putin’s actions have destabilized global order and that the wrong lessons might be learned in the Indo-Pacific by revisionist powers.

Here, Kishida’s concerns include a forceful re-unification of Taiwan by China and what that would mean for the destabilization of sea lines of communication, critical technology supply chains and trade flows.

Japan and like-minded countries and political entities in the region such as Taiwan are also anxious about the weakness of the U.N. Charter, given its inability to deter and stop Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The solicitude is further magnified by Beijing’s refusal to condemn Moscow’s actions, which contradicts its Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence that include mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual nonaggression, noninterference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit and peaceful coexistence.

What will be clear from the speeches of Kishida and Wei is that Japan and China see the region differently. This is an oversimplification of the division in views about the Indo-Pacific region.

Japan’s picture of the Indo-Pacific is broadly supported by allies and partners within the region. Southeast Asian countries, as well as South Asian countries like India, Australia, New Zealand and South Korea, and political entities such as Taiwan, share a very similar view about the importance of a rules-based order and the importance of using international law as the final arbiter of international disputes.

They strongly support the anchoring of the United States in the region not only through a security partnership, but through trade and most recently, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity. In fact, they would welcome the U.S. to return to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and to be a key player in expanding this 21st-century trade agreement that protects intellectual property rights, limits the role of state-owned enterprises and has strict environmental and labor laws.

There is also growing support for “the Quad’s” role in providing public goods to the region such as vaccines, infrastructure and connectivity. AUKUS as well is seen by many countries as another minilateral partnership to embed the U.S. and its Australian and U.K. partners in the region from the standpoint of deterrence, but also in technological cooperation in the areas of AI, quantum computing, cybersecurity and hypersonic missiles.

These two Indo-Pacific views are grounded not only in a desire for security in their backyard but in the case of China, it is also a domestic issue, directly related to the ruling regime’s security. A rules-based order in China’s backyard, an order that is transparent and an order that ensures that international law regulates the behavior of states is fundamentally contrary to China’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, especially the noninterference and the protection of sovereignty clauses.

Digging into these clauses a little more deeply we see that the protection of sovereignty and noninterference principles are often political jargon used by governments that don’t want to be held accountable for track records of human right violations and the abrogation international agreements, such as the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the subsequent collapse of the “one country, two systems” model for Hong Kong.

The securitized, state-centric worldview that China will present at the Shangri-La Dialogue is a view that is divergent with much of the Indo-Pacific region.

The Shangri-La Dialogue presents Kishida the opportunity to focus on the principles that bring much of the region together including good governance, transparency and a rules-based order. These principles were the key formula for the peace and stability that Japan has enjoyed for most of the post-WWII period. Importantly, these principles are directly linked to Japan’s return to international society as a well-respected and trusted member.

Stephen Nagy is a senior associate professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a Senior Fellow at the MacDonald Laurier Institute, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.